Alabama is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States. It borders Tennessee to the north, Georgia to the east, Florida and the Gulf of Mexico to the south, and Mississippi to the west. Alabama is the 30th largest by area and the 24th-most populous of the 50 U.S. states.

The history of what is now Alabama stems back thousands of years ago when it was inhabited by indigenous peoples. The Woodland period spanned from around 1000 BCE to 1000 CE and was marked by the development of the Eastern Agricultural Complex. This was followed by the Mississippian culture of Native Americans, which lasted to around the 1600 CE. The first Europeans to make contact with Alabama were the Spanish, with the first permanent European settlement being Mobile, established by the French in 1702.

Chilton County is a county located in the central portion of the U.S. state of Alabama. As of the 2020 census, the population was 45,014. The county seat is Clanton. Its name is in honor of William Parish Chilton, Sr. (1810–1871), a lawyer who became Chief Justice of the Alabama Supreme Court and later represented Montgomery County in the Congress of the Confederate States of America.

Clarke County is a county located in the southwestern part of the U.S. state of Alabama. As of the 2020 census, the population was 23,087. The county seat is Grove Hill. The county's largest city is Jackson. The county was created by the legislature of the Mississippi Territory in 1812. It is named in honor of General John Clarke of Georgia, who was later elected governor of that state.

Dallas County is a county located in the central part of the U.S. state of Alabama. As of the 2020 census, its population was 38,462. The county seat is Selma. Its name is in honor of United States Secretary of the Treasury Alexander J. Dallas, who served from 1814 to 1816.

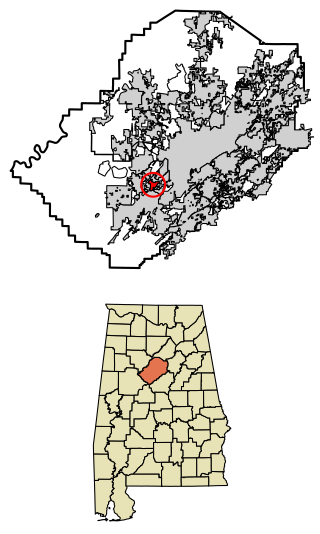

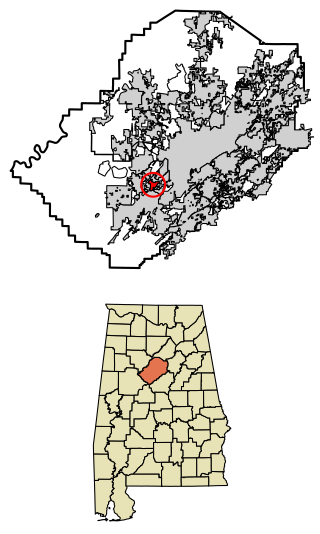

Jefferson County is the most populous county in the U.S. state of Alabama, located in the central portion of the state. As of the 2020 census, its population was 674,721. Its county seat is Birmingham. Its rapid growth as an industrial city in the 20th century, based on heavy manufacturing in steel and iron, established its dominance. Jefferson County is the central county of the Birmingham-Hoover, AL Metropolitan Statistical Area.

Lowndes County is in the central part of the U.S. state of Alabama. As of the 2020 census, the county's population was 10,311. Its county seat is Hayneville. The county is named in honor of William Lowndes, a member of the United States Congress from South Carolina.

Monroe County is a county located in the southwestern part of the U.S. state of Alabama. As of the 2020 census, the population was 19,772. Its county seat is Monroeville. Its name is in honor of James Monroe, fifth President of the United States. It is a dry county, in which the sale of alcoholic beverages is restricted or prohibited, but Frisco City and Monroeville are wet cities.

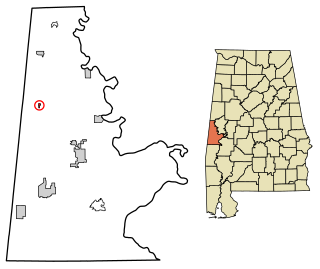

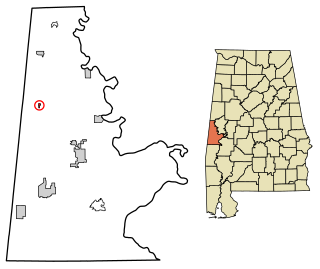

Sumter County is a county located in the west central portion of Alabama. At the 2020 census, the population was 12,345. Its county seat is Livingston. Its name is in honor of General Thomas Sumter of South Carolina. The University of West Alabama is in Livingston.

Wilcox County is a county of the U.S. state of Alabama. As of the 2020 census, the population was 10,600. Its county seat is Camden.

Selma is a city in and the county seat of Dallas County, in the Black Belt region of south central Alabama and extending to the west. Located on the banks of the Alabama River, the city has a population of 17,971 as of the 2020 census. About 80% of the population is African-American.

Colony is a town in Cullman County, Alabama, United States. At the 2010 census the population was 268, down from 385 in 2000. Colony is a historically African-American town. In its early days it was a haven for African Americans in the Deep South. It incorporated in 1981.

Brighton is a city near Birmingham, Alabama, United States and located just east of Hueytown. At the 2020 census, the population was 2,337. It is part of the Birmingham-Hoover Metropolitan Statistical Area, which in 2010 had a population of about 1,128,047, approximately one-quarter of Alabama's population.

Haleyville is a city in Winston and Marion counties in the U.S. state of Alabama. It incorporated on February 28, 1889. Most of the city is located in Winston County, with a small portion of the western limits entering Marion County. Haleyville was originally named "Davis Cross Roads", having been established at the crossroads of Byler Road and the Illinois Central Railroad. At the 2020 census the population was 4,361, up from 4,173 at the 2010 census.

Marion is a city in and the county seat of Perry County, Alabama, United States. As of the 2010 census, the population of the city is 3,686, up 4.8% over 2000. First known as Muckle Ridge, the city was renamed for a hero of the American Revolution, Francis Marion.

Emelle is a town in Sumter County, Alabama, United States. It was named after the daughters of the man who donated the land for the town. The town was started in the 19th century but not incorporated until 1981. The daughters of the man who donated were named Emma Dial and Ella Dial, so he combined the two names to create Emelle. Emelle was famous for its great cotton. The first mayor of Emelle was James Dailey. He served two terms. The current mayor is Roy Willingham Sr. The population was 32 at the 2020 census.

Talladega is the county seat of Talladega County, Alabama, United States. It was incorporated in 1835. At the 2020 census, the population was 15,861. Talladega is approximately 50 miles (80 km) east of one of the state’s largest cities, Birmingham.

The Black Belt is a region of the U.S. state of Alabama. The term originally referred to the region's rich, black soil, much of it in the soil order Vertisols. The term took on an additional meaning in the 19th century, when the region was developed for cotton plantation agriculture, in which the workers were enslaved African Americans. After the American Civil War, many freedmen stayed in the area as sharecroppers and tenant farmers, continuing to comprise a majority of the population in many of these counties.

Alabama was central to the Civil War, with the secession convention at Montgomery, the birthplace of the Confederacy, inviting other slaveholding states to form a southern republic, during January–March 1861, and to develop new state constitutions. The 1861 Alabaman constitution granted citizenship to current U.S. residents, but prohibited import duties (tariffs) on foreign goods, limited a standing military, and as a final issue, opposed emancipation by any nation, but urged protection of African-American slaves with trials by jury, and reserved the power to regulate or prohibit the African slave trade. The secession convention invited all slaveholding states to secede, but only 7 Cotton States of the Lower South formed the Confederacy with Alabama, while the majority of slave states were in the Union. Congress had voted to protect the institution of slavery by passing the Corwin Amendment on March 4, 1861, but it was never ratified.

Anthony Dickinson Sayre was an Alabama lawyer and politician who notably served as a state legislator in the Alabama House of Representatives (1890-1893), as the President of the Alabama State Senate (1896-97), and later as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of Alabama (1909-1931). Influential in Alabama politics for nearly half-a-century, Sayre is widely regarded by historians as the legal architect who laid the foundation for the state's discriminatory Jim Crow laws.