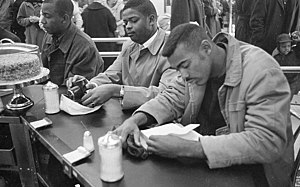

A sit-in or sit-down is a form of direct action that involves one or more people occupying an area for a protest, often to promote political, social, or economic change. The protestors gather conspicuously in a space or building, refusing to move unless their demands are met. The often clearly visible demonstrations are intended to spread awareness among the public, or disrupt the goings-on of the protested organisation. Lunch counter sit-ins were a nonviolent form of protest used to oppose segregation during the civil rights movement, and often provoked heckling and violence from those opposed to their message.

The Greensboro sit-ins were a series of nonviolent protests in February to July 1960, primarily in the Woolworth store—now the International Civil Rights Center and Museum—in Greensboro, North Carolina, which led to the F. W. Woolworth Company department store chain removing its policy of racial segregation in the Southern United States. While not the first sit-in of the civil rights movement, the Greensboro sit-ins were an instrumental action, and also the best-known sit-ins of the civil rights movement. They are considered a catalyst to the subsequent sit-in movement, in which 70,000 people participated. This sit-in was a contributing factor in the formation of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC).

The Nashville sit-ins, which lasted from February 13 to May 10, 1960, were part of a protest to end racial segregation at lunch counters in downtown Nashville, Tennessee. The sit-in campaign, coordinated by the Nashville Student Movement and the Nashville Christian Leadership Council, was notable for its early success and its emphasis on disciplined nonviolence. It was part of a broader sit-in movement that spread across the southern United States in the wake of the Greensboro sit-ins in North Carolina.

Read's Drug Store was a chain of stores based in Baltimore, Maryland. Read's Drug Store was founded by William Read. He sold it to the Nattans family in 1899. The downtown store was constructed in 1934 by Smith & May, Baltimore architects also responsible for the Bank of America building at 10 Light St. In 1929, one company slogan was "Run Right to Reads." Read's was purchased from the Nattans by Rite Aid in 1983.

The Friendship Nine, or Rock Hill Nine, was a group of African-American men who went to jail after staging a sit-in at a segregated McCrory's lunch counter in Rock Hill, South Carolina in 1961. The group gained nationwide attention because they followed the 1960 Nashville sit-ins strategy of "Jail, No Bail", which lessened the huge financial burden civil rights groups were facing as the sit-in movement spread across the South. They became known as the Friendship Nine because eight of the nine men were students at Rock Hill's Friendship Junior College.

Jibreel Khazan is a civil rights activist who is best known as a member of the Greensboro Four, a group of African American college students who, on February 1, 1960, sat down at a segregated Woolworth's lunch counter in downtown Greensboro, North Carolina challenging the store's policy of denying service to non-white customers. The protests and the subsequent events were major milestones in the Civil Rights Movement.

Clarence Lee "Curly" Harris was the store manager at the F. W. Woolworth Company store in Greensboro, North Carolina, during the Greensboro sit-ins in 1960.

Douglas E. Moore was a Methodist minister who organized the 1957 Royal Ice Cream Sit-in in Durham, North Carolina. Moore entered the ministry at a young age. After finding himself dissatisfied with what he perceived as a lack of action among his divinity peers, he decided to take a more activist course. Shortly after becoming a pastor in Durham, Moore decided to challenge the city's power structure via the Royal Ice Cream Sit-in, a protest in which he and several others sat down in the white section of an ice cream parlor and asked to be served. The sit-in failed to challenge segregation in the short run, and Moore's actions provoked a myriad of negative reactions from many white and African-American leaders, who considered his efforts far too radical. Nevertheless, Moore continued to press forward with his agenda of activism.

Clara Shepard Luper was a civic leader, schoolteacher, and pioneering leader in the American Civil Rights Movement. She is best known for her leadership role in the 1958 Oklahoma City sit-in movement, as she, her young son and daughter, and numerous young members of the NAACP Youth Council successfully conducted carefully planned nonviolent sit-in protests of downtown drugstore lunch-counters, which overturned their policies of segregation. The success of this sit-in would result in Luper becoming a leader of various sit-ins throughout Oklahoma City between 1958 and 1964. The Clara Luper Corridor is a streetscape and civic beautification project from the Oklahoma Capitol area east to northeast Oklahoma City. In 1972, Clara Luper was an Oklahoma candidate for election to the United States Senate. When asked by the press if she, a black woman, could represent white people, she responded: “Of course, I can represent white people, black people, red people, yellow people, brown people, and polka dot people. You see, I have lived long enough to know that people are people.”

The NAACP Youth Council is a branch of the NAACP in which youth are actively involved. In past years, council participants organized under the council's name to make major strides in the Civil Rights Movement. Started in 1935 by Juanita E. Jackson, special assistant to Walter White and the first NAACP Youth secretary, the NAACP National Board of Directors formally created the Youth and College Division in March 1936.

The Atlanta Student Movement was formed in February 1960 in Atlanta by students of the campuses Atlanta University Center (AUC). It was led by the Committee on the Appeal for Human Rights (COAHR) and was part of the Civil Rights Movement.

The Dockum Drug Store sit-in was one of the first organized lunch counter sit-ins for the purpose of integrating segregated establishments in the United States. The protest began on July 19, 1958 in downtown Wichita, Kansas, at a Dockum Drug Store, in which protesters would sit at the counter all day until the store closed, ignoring taunts from counter-protesters. The sit-in ended three weeks later when the owner relented and agreed to serve black patrons. Though it wasn't the first sit-in, it is notable for happening before the well known 1960 Greensboro sit-ins.

The Richmond 34 refers to a group of Virginia Union University students who participated in a nonviolent sit-in at the lunch counter of Thalhimers department store in downtown Richmond, Virginia. The event was one of many sit-ins to occur throughout the civil rights movement in the 1960s and was essential to helping desegregate the city of Richmond.

The Royal Ice Cream sit-in was a nonviolent protest in Durham, North Carolina, that led to a court case on the legality of segregated facilities. The demonstration took place on June 23, 1957 when a group of African American protesters, led by Reverend Douglas E. Moore, entered the Royal Ice Cream Parlor and sat in the section reserved for white patrons. When asked to move, the protesters refused and were arrested for trespassing. The case was appealed unsuccessfully to the County and State Superior Courts.

February One is the name of the 2002 monument dedicated to Ezell Blair Jr., Franklin McCain, Joseph McNeil and David Richmond who were collectively known as the Greensboro Four. The 15-foot bronze and marble monument is located on the western edge of the campus of North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University in Greensboro, North Carolina. James Barnhill, the sculptor who created the monument, was inspired by the historic 1960 image of the four college aged men leaving the downtown Greensboro Woolworth store after holding a sit-in protest of the company's policy of segregating its lunch counters. The sit-in protests were a significant event in the Civil Rights Movement due to increasing national sentiment of the fight for the civil rights of African-Americans during this period in American history.

David Leinail Richmond was a civil rights activist for most of his life, but he was best known for being one of the Greensboro Four. Richmond was a student at North Carolina A&T during the time of the Greensboro protests, but never ended up graduating from A&T. He felt pressure from the residual celebrity of being one of the Greensboro Four; his life was threatened in Greensboro and he was forced to move to Franklin, NC. Eventually, he moved back to Greensboro to take care of his father. Richmond was awarded the Levi Coffin Award for leadership in human rights by the Greensboro Chamber of Commerce in 1980. Richmond seemed to be haunted by the fact that he could not do more to improve his world, and battled alcoholism and depression. He died in 1990 and was awarded a posthumous honorary doctorate degree from North Carolina A&T

Houston's first sit-in was held Friday, March 4, 1960 at the Weingarten's grocery store lunch counter located at 4110 Almeda Road in Houston, Texas. This sit-in was a nonviolent, direct action protest led by more than a dozen Texas Southern University students. The sit-in was organized to protest Houston's legal segregation laws. The students met on Texas Southern University's campus and the YMCA located on Wheeler Street to organize the sit-in. They called their meetings 'war room' sessions. In these sessions, the students strategized like a military unit on how they would dismantle Houston's disenfranchisement laws. They believed that their peaceful approach was a tactic that would break Houston's discriminatory practices. It worked. The students called themselves the Progressive Youth Association (PYA). PYA was formed to address the social, political and economic issues that African-Americans faced in Houston. The Houston collegians were inspired by students at North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University, who held a sit-in in Greensboro, North Carolina on February 1, 1960.

The Katz Drug Store sit-in was one of the first sit-ins during the civil rights movement, occurring between August 19 and August 21, 1958, in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. In protest of racial discrimination, black schoolchildren sat at a lunch counter with their teacher demanding food, refusing to leave until they were served. They sought to end the racial segregation of eating places in their city, sparking a sit-in movement in Oklahoma City that lasted for years.

The New Year's Day March in Greenville, South Carolina was a 1,000-man march that protested the segregated facilities at the Greenville Municipal Airport, now renamed the Greenville Downtown Airport. The march occurred after Richard Henry and Jackie Robinson were prohibited from using a white-only waiting room at the airport. The march was the first large-scale movement of the civil rights movement in South Carolina and Greenville. The march brought state-wide attention to segregation, and the case Henry v. Greenville Airport Commission (1961) ultimately required the airport's integration of its facilities.

The Atlanta sit-ins were a series of sit-ins that took place in Atlanta, Georgia, United States. Occurring during the sit-in movement of the larger civil rights movement, the sit-ins were organized by the Committee on Appeal for Human Rights, which consisted of students from the Atlanta University Center. The sit-ins were inspired by the Greensboro sit-ins, which had started a month earlier in Greensboro, North Carolina with the goal of desegregating the lunch counters in the city. The Atlanta protests lasted for almost a year before an agreement was made to desegregate the lunch counters in the city.