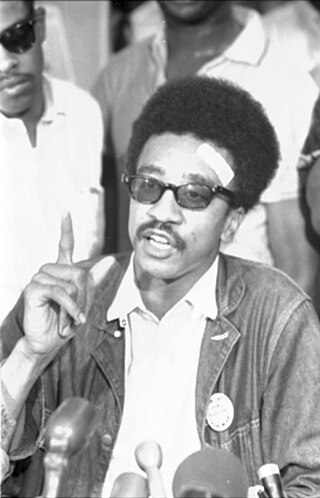

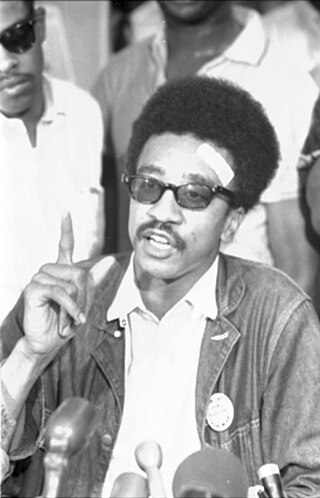

Jamil Abdullah al-Amin, is an American human rights activist, Muslim cleric, black separatist, and convicted murderer who was the fifth chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) in the 1960s. Best known as H. Rap Brown, he served as the Black Panther Party's minister of justice during a short-lived alliance between SNCC and the Black Panther Party.

Denmark is a city in Bamberg County, South Carolina, United States. The population at the 2010 census is 3,538.

The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee was the principal channel of student commitment in the United States to the civil rights movement during the 1960s. Emerging in 1960 from the student-led sit-ins at segregated lunch counters in Greensboro, North Carolina, and Nashville, Tennessee, the Committee sought to coordinate and assist direct-action challenges to the civic segregation and political exclusion of African Americans. From 1962, with the support of the Voter Education Project, SNCC committed to the registration and mobilization of black voters in the Deep South. Affiliates such as the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party and the Lowndes County Freedom Organization in Alabama also worked to increase the pressure on federal and state government to enforce constitutional protections.

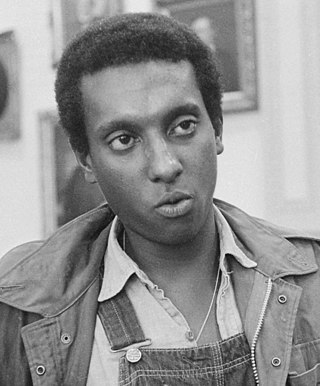

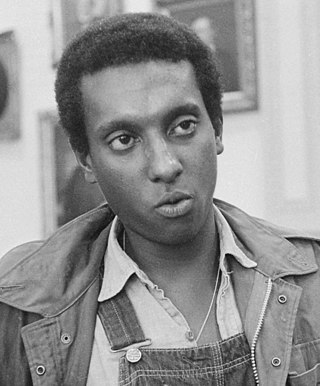

Kwame Ture was an American organizer in the civil rights movement in the United States and the global pan-African movement. Born in Trinidad in the Caribbean, he grew up in the United States from the age of 11 and became an activist while attending the Bronx High School of Science. He was a key leader in the development of the Black Power movement, first while leading the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), then as the "Honorary Prime Minister" of the Black Panther Party (BPP), and last as a leader of the All-African People's Revolutionary Party (A-APRP).

The March Against Fear was a major 1966 demonstration in the Civil Rights Movement in the South. Activist James Meredith launched the event on June 5, 1966, intending to make a solitary walk from Memphis, Tennessee, to Jackson, Mississippi via the Mississippi Delta, starting at Memphis's Peabody Hotel and proceeding to the Mississippi state line, then continuing through, respectively, the Mississippi cities of Hernando, Grenada, Greenwood, Indianola, Belzoni, Yazoo City, and Canton before arriving at Jackson's City Hall. The total distance marched was approximately 270 miles over a period of 21 days. The goal was to counter the continuing racism in the Mississippi Delta after passage of federal civil rights legislation in the previous two years and to encourage African Americans in the state to register to vote. He invited only individual black men to join him and did not want it to be a large media event dominated by major civil rights organizations.

The Orangeburg Massacre was a shooting of student protesters that took place on February 8, 1968, on the campus of South Carolina State College in Orangeburg, South Carolina, United States. Nine Highway Patrolmen and one city police officer opened fire on a crowd of African American students, killing three and injuring twenty-eight. The shootings were the culmination of a series of protests against racial segregation at a local bowling alley, marking the first instance of police killing student protestors at an American university.

James Forman was a prominent African-American leader in the civil rights movement. He was active in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), the Black Panther Party, and the League of Revolutionary Black Workers. As the executive secretary of SNCC from 1961 to 1966, Forman played a significant role in the Freedom Rides, the Albany movement, the Birmingham campaign, and the Selma to Montgomery marches.

The Greensboro sit-ins were a series of nonviolent protests in February to July 1960, primarily in the Woolworth store—now the International Civil Rights Center and Museum—in Greensboro, North Carolina, which led to the F. W. Woolworth Company department store chain removing its policy of racial segregation in the Southern United States. While not the first sit-in of the civil rights movement, the Greensboro sit-ins were an instrumental action, and also the best-known sit-ins of the civil rights movement. They are considered a catalyst to the subsequent sit-in movement, in which 70,000 people participated. This sit-in was a contributing factor in the formation of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC).

Jehudah Menachem Mendel "Mendy" Samstein was an American civil rights activist.

Jack Minnis (1926-2005) was an American activist, and the founder and director of opposition research for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee in the Civil Rights Movement era. Minnis researched federal expenditures and state and local subversion of racial equality. Minnis was white, but remained affiliated with SNCC even after it adopted a "blacks only" personnel policy, its only white employee for a long time. He helped to train such workers as Stokely Carmichael, Marion Barry, and John Lewis.

The Freedom Singers originated as a quartet formed in 1962 at Albany State College in Albany, Georgia. After folk singer Pete Seeger witnessed the power of their congregational-style of singing, which fused black Baptist a cappella church singing with popular music at the time, as well as protest songs and chants. Churches were considered to be safe spaces, acting as a shelter from the racism of the outside world. As a result, churches paved the way for the creation of the freedom song. After witnessing the influence of freedom songs, Seeger suggested The Freedom Singers as a touring group to the SNCC executive secretary James Forman as a way to fuel future campaigns. Intrinsically connected, their performances drew aid and support to the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) during the emerging civil rights movement. As a result, communal song became essential to empowering and educating audiences about civil rights issues and a powerful social weapon of influence in the fight against Jim Crow segregation. Their most notable song “We Shall Not Be Moved” translated from the original Freedom Singers to the second generation of Freedom Singers, and finally to the Freedom Voices, made up of field secretaries from SNCC. "We Shall Not Be Moved" is considered by many to be the "face" of the Civil Rights movement. Rutha Mae Harris, a former freedom singer, speculated that without the music force of broad communal singing, the civil rights movement may not have resonated beyond of the struggles of the Jim Crow South. Since the Freedom Singers were so successful, a second group was created called the Freedom Voices.

Charles Melvin Sherrod was an American minister and civil rights activist. During the civil rights movement, Sherrod helped found the Albany Movement while serving as field secretary for southwest Georgia for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. He also participated in the Selma Voting Rights Movement and in many other campaigns of the civil rights movement of that era.

Judy Richardson is an American documentary filmmaker and civil rights activist. She was Distinguished Visiting Lecturer of Africana Studies at Brown University.

Charles "Chuck" McDew was an American lifelong activist for racial equality and a former activist of the Civil Rights Movement. After attending South Carolina State University, he became the chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) from 1960 to 1963. His involvement in the movement earned McDew the title, "black by birth, a Jew by choice and a revolutionary by necessity" stated by fellow SNCC activist Bob Moses.

Samuel Leamon Younge Jr. was a civil rights and voting rights activist who was murdered for trying to desegregate a "whites only" restroom. Younge was an enlisted service member in the United States Navy, where he served for two years before being medically discharged. Younge was an active member of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and a leader of the Tuskegee Institute Advancement League.

This is a timeline of the civil rights movement in the United States, a nonviolent mid-20th century freedom movement to gain legal equality and the enforcement of constitutional rights for people of color. The goals of the movement included securing equal protection under the law, ending legally institutionalized racial discrimination, and gaining equal access to public facilities, education reform, fair housing, and the ability to vote.

The Cambridge movement was an American social movement in Dorchester County, Maryland, led by Gloria Richardson and the Cambridge Nonviolent Action Committee. Protests continued from late 1961 to the summer of 1964. The movement led to the desegregation of all schools, recreational areas, and hospitals in Maryland and the longest period of martial law within the United States since 1877. Many cite it as the birth of the Black Power movement.

The Atlanta sit-ins were a series of sit-ins that took place in Atlanta, Georgia, United States. Occurring during the sit-in movement of the larger civil rights movement, the sit-ins were organized by the Committee on Appeal for Human Rights, which consisted of students from the Atlanta University Center. The sit-ins were inspired by the Greensboro sit-ins, which had started a month earlier in Greensboro, North Carolina with the goal of desegregating the lunch counters in the city. The Atlanta protests lasted for almost a year before an agreement was made to desegregate the lunch counters in the city.

John Robert Zellner is an American civil rights activist. He graduated from Huntingdon College in 1961 and that year became a member of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) as its first white field secretary. Zellner was involved in numerous civil rights efforts, including nonviolence workshops at Talladega College, protests for integration in Danville, Virginia, and organizing Freedom Schools in Greenwood, Mississippi, in 1964. He also investigated the murders of Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner that summer.