Abraham Joshua Heschel was a Polish-American rabbi and one of the leading Jewish theologians and Jewish philosophers of the 20th century. Heschel, a professor of Jewish mysticism at the Jewish Theological Seminary of America, authored a number of widely read books on Jewish philosophy and was a leader in the civil rights movement.

The civil rights movement was a social movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized racial segregation, discrimination, and disenfranchisement in the country. The movement had its origins in the Reconstruction era during the late 19th century and had its modern roots in the 1940s, although the movement made its largest legislative gains in the 1960s after years of direct actions and grassroots protests. The social movement's major nonviolent resistance and civil disobedience campaigns eventually secured new protections in federal law for the civil rights of all Americans.

Asa Philip Randolph was an American labor unionist and civil rights activist. In 1925, he organized and led the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the first successful African-American-led labor union. In the early Civil Rights Movement and the Labor Movement, Randolph was a prominent voice. His continuous agitation with the support of fellow labor rights activists against racist labor practices helped lead President Franklin D. Roosevelt to issue Executive Order 8802 in 1941, banning discrimination in the defense industries during World War II. The group then successfully maintained pressure, so that President Harry S. Truman proposed a new Civil Rights Act and issued Executive Orders 9980 and 9981 in 1948, promoting fair employment and anti-discrimination policies in federal government hiring, and ending racial segregation in the armed services.

The American Jewish Committee (AJC) is a Jewish advocacy group established on November 11, 1906. It is one of the oldest Jewish advocacy organizations and, according to The New York Times, is "widely regarded as the dean of American Jewish organizations". As of 2009, AJC envisions itself as the "Global Center for Jewish and Israel Advocacy".

Roy Ottoway Wilkins was an American civil rights leader from the 1930s to the 1970s. Wilkins' most notable role was his leadership of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), in which he held the title of Executive Secretary from 1955 to 1963 and Executive Director from 1964 to 1977. Wilkins was a central figure in many notable marches of the civil rights movement and made contributions to African-American literature. He controversially advocated for African-Americans to join the military.

Joel Elias Spingarn was an American educator, literary critic, civil rights activist, military intelligence officer, and horticulturalist.

Jewish Voice for Peace is an American anti-Zionist left-wing Jewish advocacy organization that is critical of Israel's occupation of the Palestinian territories, and supports the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) campaign against Israel.

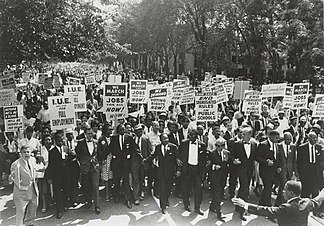

The Big Six—Martin Luther King Jr., James Farmer, John Lewis, A. Philip Randolph, Roy Wilkins and Whitney Young—were the leaders of six prominent civil rights organizations who were instrumental in the organization of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in 1963, at the height of the Civil Rights Movement in the United States.

The American Jewish Congress (AJCongress) is an association of American Jews organized to defend Jewish interests at home and abroad through public policy advocacy, using diplomacy, legislation, and the courts.

Arthur Barnette Spingarn was an American leader in the fight for civil rights for African Americans.

Xernona Clayton Brady is an American civil rights leader and broadcasting executive. During the Civil Rights Movement, she worked for the National Urban League and Southern Christian Leadership Conference, where she became involved in the work of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Later, Clayton went into television, where she became the first African American from the southern United States to host a daily prime time talk show. She became corporate vice president for Turner Broadcasting.

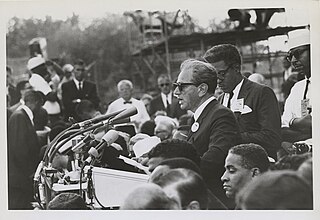

Joachim Prinz was a German-American rabbi who was an outspoken activist against Nazism in Germany in the 1930s and later became a leader in the civil rights movement in the United States in the 1960s.

Antisemitism has long existed in the United States. Most Jewish community relations agencies in the United States draw distinctions between antisemitism, which is measured in terms of attitudes and behaviors, and the security and status of American Jews, which are both measured by the occurrence of specific incidents.

Marc H. Tanenbaum (1925–1992) was a human rights and social justice activist and rabbi. He was known for building bridges with other faith communities to advance mutual understanding and co-operation and to eliminate entrenched stereotypes, particularly ones rooted in religious teachings.

The St. Augustine movement was a part of the wider Civil Rights Movement, taking place in St. Augustine, Florida from 1963 to 1964. It was a major event in the city's long history and had a role in the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is a civil rights organization in the United States, formed in 1909 as an interracial endeavor to advance justice for African Americans by a group including W. E. B. Du Bois, Mary White Ovington, Moorfield Storey, Ida B. Wells, Lillian Wald, and Henry Moskowitz. Over the years, leaders of the organization have included Thurgood Marshall and Roy Wilkins.

The Anti-Defamation League (ADL), formerly known as the Anti-Defamation League of B'nai B'rith, is a New York–based international Jewish non-governmental organization and advocacy group.

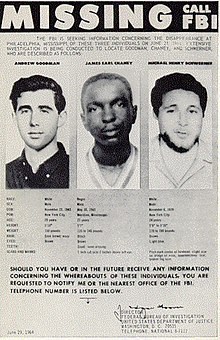

African Americans and Jewish Americans have interacted throughout much of the history of the United States. This relationship has included widely publicized cooperation and conflict, and—since the 1970s—it has been an area of significant academic research. Cooperation during the Civil Rights Movement was strategic and significant, culminating in the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

The Foundation for Ethnic Understanding (FFEU) is a not-for-profit organization based in New York that focuses on improving Muslim–Jewish relations and Black–Jewish relations. FFEU was founded in 1989 by Rabbi Marc Schneier and theatrical producer and director Joseph Papp. The goals of the organization are in part motivated by the historical cooperation between African Americans and Jewish Americans during the Civil Rights Movement. Russell Simmons joined the Board of the Foundation for Ethnic Understanding in 2002 as chairman of the board. In 2007, the Foundation began its program in Muslim–Jewish Relations and has since hosted the First National Summit of Imams and Rabbis, two European conferences of Muslim and Jewish Leaders, three Missions of Muslim and Jewish Leaders to Washington D.C., and has held the annual program "The Weekend of Twinning" each November since 2008.