The civil rights movement was a nonviolent social movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized racial segregation, discrimination, and disenfranchisement in the country. The movement had its origins in the Reconstruction era during the late 19th century and had its modern roots in the 1940s, although the movement made its largest legislative gains in the 1960s after years of direct actions and grassroots protests. The social movement's major nonviolent resistance and civil disobedience campaigns eventually secured new protections in federal law for the civil rights of all Americans.

Union County is a county located in the U.S. state of North Carolina. As of the 2020 census, the population was 238,267. Its county seat is Monroe. Union County is included in the Charlotte-Concord-Gastonia, NC-SC Metropolitan Statistical Area.

Monroe is a city in and the county seat of Union County, North Carolina, United States. The population increased from 32,797 in 2010 to 34,551 in 2020. It is within the rapidly growing Charlotte metropolitan area. Monroe has a council-manager form of government.

The Deacons for Defense and Justice was an armed African-American self-defense group founded in November 1964, during the civil rights era in the United States, in the mill town of Jonesboro, Louisiana. On February 21, 1965—the day of Malcolm X's assassination—the first affiliated chapter was founded in Bogalusa, Louisiana, followed by a total of 20 other chapters in this state, Mississippi, Arkansas, and Alabama. It was intended to protect civil rights activists and their families, threatened both by white vigilantes and discriminatory treatment by police under Jim Crow laws. The Bogalusa chapter gained national attention during the summer of 1965 in its violent struggles with the Ku Klux Klan.

Walter Francis White was an American civil rights activist who led the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) for a quarter of a century, from 1929 until 1955. He directed a broad program of legal challenges to racial segregation and disfranchisement. He was also a journalist, novelist, and essayist.

Robert Franklin Williams was an American civil rights leader and author best known for serving as president of the Monroe, North Carolina chapter of the NAACP in the 1950s and into 1961. He succeeded in integrating the local public library and swimming pool in Monroe. At a time of high racial tension and official abuses, Williams promoted armed Black self-defense in the United States. In addition, he helped gain support for gubernatorial pardons in 1959 for two young African-American boys who had received lengthy reformatory sentences in what was known as the Kissing Case of 1958.

The civil rights movement (1896–1954) was a long, primarily nonviolent action to bring full civil rights and equality under the law to all Americans. The era has had a lasting impact on American society – in its tactics, the increased social and legal acceptance of civil rights, and in its exposure of the prevalence and cost of racism.

The Enforcement Act of 1871, also known as the Ku Klux Klan Act, Third Enforcement Act, Third Ku Klux Klan Act, Civil Rights Act of 1871, or Force Act of 1871, is an Act of the United States Congress which empowered the President to suspend the writ of habeas corpus to combat the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) and other terrorist organizations who had terrorized and murdered innocent African Americans, public officials, and White sympathizers in the previous Confederate States of America. The act was passed by the 42nd United States Congress and signed into law by United States President Ulysses S. Grant on April 20, 1871. The act was the last of three Enforcement Acts passed by the United States Congress from 1870 to 1871 during the Reconstruction Era to combat attacks upon the suffrage rights of African Americans. The statute has been subject to only minor changes since then, but has been the subject of voluminous interpretation by courts.

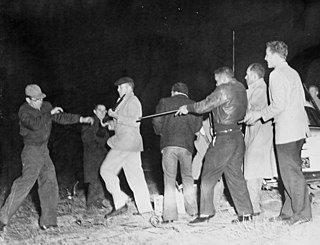

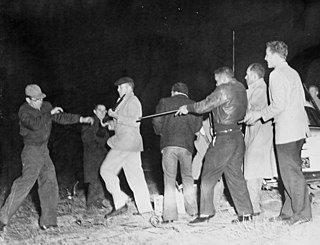

The Battle of Hayes Pond, also known as the Battle of Maxton Field or the Maxton Riot, was an armed confrontation between members of a Ku Klux Klan (KKK) organization and Lumbee Indians at a Klan rally near Maxton, North Carolina, on the night of January 18, 1958. The clash resulted in the disruption of the rally and a significant amount of media coverage praising the Lumbees and condemning the Klansmen.

James William "Catfish" Cole was an American soldier and evangelist who was leader of the Ku Klux Klan of North Carolina and South Carolina, serving as a Grand Dragon.

Vernon Ferdinand Dahmer Sr. was an American civil rights movement leader and president of the Forrest County chapter of the NAACP in Hattiesburg, Mississippi. He was murdered by the White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan for his work on recruiting Black Americans to vote.

The St. Augustine movement was a part of the wider Civil Rights Movement, taking place in St. Augustine, Florida from 1963 to 1964. It was a major event in the city's long history and had a role in the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Mae Mallory was an activist of the Civil Rights Movement and a Black Power movement leader active in the 1950s and 1960s. She is best known as an advocate of school desegregation and of black armed self-defense.

Conrad Joseph Lynn was an African-American civil rights lawyer and activist known for providing legal representation for activists, including many unpopular defendants. Among the causes he supported as a lawyer were civil rights, Puerto Rican nationalism, and opposition to the draft during both World War II and the Vietnam War. The controversial defendants he represented included civil rights activist Robert F. Williams and Black Panther leader H. Rap Brown.

Golden Asro Frinks was an American civil rights activist and a Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) field secretary who represented the New Bern, North Carolina SCLC chapter. He is best known as a principal civil rights organizer in North Carolina during the 1960s.

Gloria Blackwell, also known as Gloria Rackley, was an African-American civil rights activist and educator. She was at the center of the Civil Rights Movement in Orangeburg, South Carolina during the 1960s, attracting some national attention and a visit by Dr. Martin Luther King of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. Her activities were widely covered by the local press.

Malcolm Buie Seawell was an American lawyer and politician. A member of the Democratic Party, he served as North Carolina Attorney General from 1958 to 1960. Seawell was raised in Lee County, North Carolina. After law school, he moved to Lumberton and joined a law firm. From 1942 to 1945 he worked for the U.S. Department of War in Washington, D.C. He then returned to Lumberton and successfully ran for the office of mayor in 1947. He held the post until the following year when he was appointed 9th Solicitorial District Solicitor. While working as solicitor Seawell gained state-wide prominence for his aggressive efforts to prosecute the Ku Klux Klan (KKK), and was credited for ultimately pushing the organization out of Robeson County. Governor Luther H. Hodges later made him a judge before appointing him Attorney General of North Carolina in 1958 to fill a vacancy.

The New Year's Day March in Greenville, South Carolina was a 1,000-man march that protested the segregated facilities at the Greenville Municipal Airport, now renamed the Greenville Downtown Airport. The march occurred after Richard Henry and Jackie Robinson were prohibited from using a white-only waiting room at the airport. The march was the first large-scale movement of the civil rights movement in South Carolina and Greenville. The march brought state-wide attention to segregation, and the case Henry v. Greenville Airport Commission (1961) ultimately required the airport's integration of its facilities.

On October 17, 1871, U.S. President Ulysses Grant declared nine South Carolina counties to be in active rebellion, and suspended habeas corpus. The order allowed federal troops, under the command of Major Lewis Merrill, to execute mass-arrests and begin the process of crushing the South Carolina Ku Klux Klan in federal court. Merrill reported 169 arrests in York County before January 1872. Numerous Klansmen fled the state, and more were quieted by fear of prosecution. Nearly 500 men surrendered to Merrill voluntarily, gave confessions or evidence, and were released. At the Fourth Federal Circuit Court session in Columbia, South Carolina beginning November 1871, United States District Attorney David T. Corbin and South Carolina Attorney General Daniel H. Chamberlain convicted 5 Klansmen in trial court, and secured convictions based on confession from 49 others. In the next Fourth Federal Circuit Court session in Charleston, South Carolina in April 1872, Corbin convicted 86 more Klansmen. Klan activities vanished while prosecutions were ongoing and publicized, but, by the end of 1872, federal will dissolved in the face of waning Republican support for Reconstruction. At the end of 1872 some 1,188 Enforcement Act cases remained to be tried. White Northern interests began to seek a more conciliatory relationship with Southern states, and lamented Southern papers' exaggerated tales of "bayonet rule." During the summer of 1873, President Grant announced a policy of clemency for those Klansmen who had not yet been tried, and pardon for those who had. The remaining cases were not tried, and prosecutions under the Enforcement Acts were all but abandoned after 1874.

Ruth Willis Perry was an American librarian, journalist, and civil rights activist. She is known for her work with the Miami chapter of the NAACP and her stand against the Johns Committee, also known as the Florida Legislative Investigation Committee, which investigated alleged subversive actions by the NAACP.