The civil rights movement was a social movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized racial segregation, discrimination, and disenfranchisement in the country. The movement had its origins in the Reconstruction era during the late 19th century and had its modern roots in the 1940s, although the movement made its largest legislative gains in the 1960s after years of direct actions and grassroots protests. The social movement's major nonviolent resistance and civil disobedience campaigns eventually secured new protections in federal law for the civil rights of all Americans.

The Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) is an African-American civil rights organization based in Atlanta, Georgia. SCLC is closely associated with its first president, Martin Luther King Jr., who had a large role in the American civil rights movement.

Racial equality is when people of all races and ethnicities are treated in an egalitarian/equal manner. Racial equality occurs when institutions give individuals legal, moral, and political rights. In present-day Western society, equality among races continues to become normative. Prior to the early 1960s, attaining equality was difficult for African, Asian, and Indigenous people. However, in more recent years, legislation is being passed ensuring that all individuals receive equal opportunities in treatment, education, employment, and other areas of life. Racial equality can refer to equal opportunities or formal equality based on race or refer to equal representation or equality of outcomes for races, also called substantive equality.

This is a timeline of African-American history, the part of history that deals with African Americans.

Donald Lee Hollowell was an American civil rights attorney during the Civil Rights Movement, in the state of Georgia. He successfully sued to integrate Atlanta's public schools, Georgia colleges, universities and public transit, freed Martin Luther King Jr. from prison, and mentored civil rights attorneys. The first black regional director of a federal agency, Hollowell is best remembered for his instrumental role in winning the desegregation of the University of Georgia in 1961. He is the subject of a 2010 documentary film, Donald L. Hollowell: Foot Soldier for Equal Justice.

Lillian Eugenia Smith was a writer and social critic of the Southern United States, known for both her non-fiction and fiction works, including the best-selling novel Strange Fruit (1944). Smith was a White woman who openly embraced controversial positions on matters of race and gender equality. She was a southern liberal who was unafraid to criticize segregation and to work toward the dismantling of Jim Crow laws at a time when such actions virtually guaranteed social ostracism.

The 1906 Atlanta Race Massacre, also known as the 1906 Atlanta Race Riot, was an episode of mass racial violence against African Americans in the United States in September 1906. Violent attacks by armed mobs of White Americans against African Americans in Atlanta, Georgia, began after newspapers, on the evening of September 22, 1906, published several unsubstantiated and luridly detailed reports of the alleged rapes of 4 local women by black men. The violence lasted through September 24, 1906. The events were reported by newspapers around the world, including the French Le Petit Journal which described the "lynchings in the USA" and the "massacre of Negroes in Atlanta," the Scottish Aberdeen Press & Journal under the headline "Race Riots in Georgia," and the London Evening Standard under the headlines "Anti-Negro Riots" and "Outrages in Georgia." The final death toll of the conflict is unknown and disputed, but officially at least 25 African Americans and two whites died. Unofficial reports ranged from 10–100 black Americans killed during the massacre. According to the Atlanta History Center, some black Americans were hanged from lampposts; others were shot, beaten or stabbed to death. They were pulled from street cars and attacked on the street; white mobs invaded black neighborhoods, destroying homes and businesses.

The Commission on Interracial Cooperation (1918–1944) was an organization founded in Atlanta, Georgia, December 18, 1918, and officially incorporated in 1929. Will W. Alexander, pastor of a local white Methodist church, was head of the organization. It was formed in the aftermath of violent race riots that occurred in 1917 in several southern cities. In 1944 it merged with the Southern Regional Council.

Disfranchisement after the Reconstruction era in the United States, especially in the Southern United States, was based on a series of laws, new constitutions, and practices in the South that were deliberately used to prevent black citizens from registering to vote and voting. These measures were enacted by the former Confederate states at the turn of the 20th century. Efforts were also made in Maryland, Kentucky, and Oklahoma. Their actions were designed to thwart the objective of the Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, ratified in 1870, which prohibited states from depriving voters of their voting rights on the basis of race. The laws were frequently written in ways to be ostensibly non-racial on paper, but were implemented in ways that selectively suppressed black voters apart from other voters.

Jessie Daniel Ames was a suffragist and civil rights leader from Texas who helped create the anti-lynching movement in the American South. She was one of the first Southern white women to speak out and work publicly against lynching of African Americans, murders which white men claimed to commit in an effort to protect women's "virtue." Despite risks to her personal safety, Ames stood up to these men and led organized efforts by white women to protest lynchings. She gained 40,000 signatures of Southern white women to oppose lynching, helping change attitudes and bring about a decline in these murders in the 1930s and 1940s.

Voter Education Project(VEP) raised and distributed foundation funds to civil rights organizations for voter education and registration work in the southern United States from 1962 to 1992. The project was federally endorsed by the Kennedy administration in hopes that the organizations of the ongoing Civil Rights Movement would shift their focus away from demonstrations and more towards the support of voter registration.

The North Carolina Commission on Interracial Cooperation was a state affiliate of the Commission on Interracial Cooperation, established in 1921 to improve race relations by changing racial attitudes and alleviating injustice. Activities included creating pamphlets, radio programs, press releases, and holding local meetings and conferences. The NCCIC was initially made up of a group of prominent individuals, both African American and white. Chairs of the NCCIC included William Louis Poteat, Howard Odum, and Edwin Pennick. Directors included L. R. Reynolds, Earnest Arnold, and Cyrus M. Johnson.

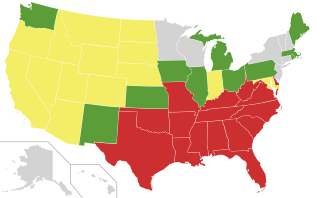

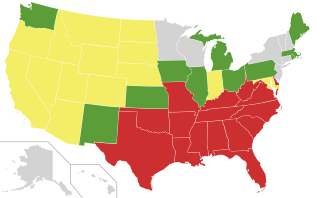

In the United States, many U.S. states historically had anti-miscegenation laws which prohibited interracial marriage and, in some states, interracial sexual relations. Some of these laws predated the establishment of the United States, and some dated to the later 17th or early 18th century, a century or more after the complete racialization of slavery. Nine states never enacted anti-miscegenation laws, and 25 states had repealed their laws by 1967. In that year, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Loving v. Virginia that such laws are unconstitutional under the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

Racial segregation in Atlanta has known many phases after the freeing of the slaves in 1865: a period of relative integration of businesses and residences; Jim Crow laws and official residential and de facto business segregation after the Atlanta Race Riot of 1906; blockbusting and black residential expansion starting in the 1950s; and gradual integration from the late 1960s onwards. A 2015 study conducted by Nate Silver of fivethirtyeight.com, found that Atlanta was the second most segregated city in the U.S. and the most segregated in the South.

Grace Towns Hamilton was an American politician who was the first African-American woman elected to the Georgia General Assembly. As executive director of the Atlanta Urban League from 1943 to 1960, Hamilton was involved in issues of housing, health care, schools and voter registration within the black community. She was 1964 co-founder of the bi-racial Partners for Progress to help government and the private sector effect compliance with the Civil Rights Act of 1964. In 1973, Hamilton became a principal architect for the revision of the Atlanta City Charter. She was advisor to the United States Civil Rights Commission from 1985 to 1987.

Dorothy Eugenia Rogers Tilly was an American civil rights activist from the progressive era until her death. She was a noted activist in the Women's Missionary Society (WMS), Commission on Interracial Cooperation (CIC), Association of Southern Women for the Prevention of Lynching, Southern Regional Council, Fulton-DeKalb Commission on Interracial Cooperation, and Fellowship of the Concerned (FOC). She was also appointed to the President's Committee on Civil Rights in 1946 by Harry S. Truman.

The Association of Southern Women for the Prevention of Lynching (ASWPL) was a women's organization founded by Jessie Daniel Ames in Atlanta, Georgia in November 1930, to lobby and campaign against the lynching of African Americans. The group was made up of middle and upper-class white women. While active, the group had "a presence in every county in the South" of the United States. It was loosely organized and only accepted white women as members because they "believed that only white women could influence other white women." Many of the women involved were also members of missionary societies. Along with the Commission on Interracial Cooperation (CIC), the ASWPL had an important effect on popular opinion among whites relating to lynching.

This is a timeline of the civil rights movement in the United States, a nonviolent mid-20th century freedom movement to gain legal equality and the enforcement of constitutional rights for people of color. The goals of the movement included securing equal protection under the law, ending legally institutionalized racial discrimination, and gaining equal access to public facilities, education reform, fair housing, and the ability to vote.

William Henry Steward was a civil rights activist from Louisville, Kentucky. In February 1876, he was appointed the first black letter carrier in Kentucky. He was the leading layman of the General Association of Negro Baptists in Kentucky and played a key role in the founding of Simmons College of Kentucky by the group in 1879. He continued to play an important role in the college during his life. He was also co-founder of the American Baptist, a journal associated with the group, and Steward went on to be the journal's editor. He was a leader in Louisville civic and public life, and played a role in extending educational opportunities in the city to black children. In 1897, his political associations led to his appointment as judge of registration and election for the Fifteenth Precinct of the Ninth Ward, overseeing voter registration for the election. This was the first appointment of an African American to such a position in Kentucky. He was elected president of the Afro-American Press Association in the 1890s He was a close associate of Booker T. Washington, and in the late 1890s and early 1900s, Steward was a prominent member of the National Afro-American Council, which was dominated by Washington. He was president of the council from 1904 to 1905. He was a lifelong opponent of segregation and was frequently involved in anti-Jim Crow law activities. In 1914 he helped found a Louisville branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), which he left in 1920 to become a key player in the Commission on Interracial Cooperation (CIC). He was also a prominent freemason and twice elected Worshipful Master of the Grand Lodge of Kentucky.

Josephine Mathewson Wilkins was an American social activist, president of the Georgia State League of Women Voters. She is a 2022 inductee into the Georgia Women of Achievement.