Robert George Seale is an American political activist and author. Seale is widely known for co-founding the Black Panther Party with fellow activist Huey P. Newton. Founded as the "Black Panther Party for Self-Defense", the Party's main practice was monitoring police activities and challenging police brutality in Black communities, first in Oakland, California, and later in cities throughout the United States.

Leroy Eldridge Cleaver was an American writer and political activist who became an early leader of the Black Panther Party.

Huey Percy Newton was an African American revolutionary and political activist who founded the Black Panther Party. He ran the party as its first leader and crafted its ten-point manifesto with Bobby Seale in 1966.

Robert James Hutton, also known as "Lil' Bobby", was the treasurer and first recruit to join the Black Panther Party. Alongside Eldridge Cleaver and other Panthers, he was involved in a confrontation with Oakland police that wounded two officers. Hutton was killed by the police under disputed circumstances. Cleaver stated Hutton was shot while surrendering with his hands up, while police stated he ignored commands and tried to flee.

Elaine Brown is an American prison activist, writer, singer, and former Black Panther Party chairwoman who is based in Oakland, California. Brown briefly ran for the Green Party presidential nomination in 2008.

The black power movement or black liberation movement was a branch or counterculture within the civil rights movement of the United States, reacting against its more moderate, mainstream, or incremental tendencies and motivated by a desire for safety and self-sufficiency that was not available inside redlined African American neighborhoods. Black power activists founded black-owned bookstores, food cooperatives, farms, media, printing presses, schools, clinics and ambulance services.

A Taste of Power: A Black Woman's Story is a memoir written by Elaine Brown. The book follows her life from childhood up through her activism with the Black Panther Party. In the early chapters of the book, Brown recalls growing up on York Street in a rough neighborhood of North Philadelphia. Due to her mother's persistence, she is able to attend an experimental elementary school in a nice neighborhood and becomes friends with some Jewish girls. From that point on, Brown describes being a part of two worlds. She'd act "white" while hanging out with her school friends, and "black" when with the girls in her neighborhood.

David Hilliard is a former member of the Black Panther Party, having served as Chief of Staff. He became a visiting instructor at the University of New Mexico in 2006. He also is the founder of the Dr. Huey P. Newton foundation.

Various American fugitives in Cuba have found political asylum in Cuba after participating in militant activities in the Black power movement or the Independence movement in Puerto Rico. Other fugitives in Cuba include defected CIA agents and others. The Cuban government formed formal ties with the Black Panther Party in the 1960s, and many fugitive Black Panthers would find political asylum in Cuba, but after their activism was seen being repressed in Cuba many became disillusioned. House Concurrent Resolution 254, passed in 1998, put the number at 90. One estimate, c. 2000, put the number at approximately 100.

Emory Douglas is an American graphic artist. He was a member of the Black Panther Party from 1967 until the Party disbanded in the 1980s. As a revolutionary artist and the Minister of Culture for the Black Panther Party, Douglas created iconography to represent black-American oppression.

The Black Panther Party was a Marxist–Leninist and black power political organization founded by college students Bobby Seale and Huey P. Newton in October 1966 in Oakland, California. The party was active in the United States between 1966 and 1982, with chapters in many major American cities, including San Francisco, New York City, Chicago, Los Angeles, Seattle, and Philadelphia. They were also active in many prisons and had international chapters in the United Kingdom and Algeria. Upon its inception, the party's core practice was its open carry patrols ("copwatching") designed to challenge the excessive force and misconduct of the Oakland Police Department. From 1969 onward, the party created social programs, including the Free Breakfast for Children Programs, education programs, and community health clinics. The Black Panther Party advocated for class struggle, claiming to represent the proletarian vanguard.

Revolutionary Suicide is an autobiography written by Huey P. Newton with assistance from J. Herman Blake originally published in 1973. Newton was a major figure in the American black liberation movement and in the wider 1960s counterculture. He was a co-founder and leader of what was then known as the Black Panther Party (BPP) for Self-Defence with Bobby Seale. The Chief ideologue and strategist of the BPP, Newton taught himself how to read during his last year of high school, which led to his enrollment in Merrit College in Oakland in 1966; the same year he formed the BPP. The Party urged members to challenge the status quo with armed patrols of the impoverished streets of Oakland, and to form coalitions with other oppressed groups. The party spread across America and internationally as well, forming coalitions with the Vietnamese, Chinese, and Cubans. This autobiography is an important work that combines political manifesto and political philosophy along with the life story of a young African American revolutionary. The book was not universally well received but has had a lasting influence on the black civil rights movement.

Michael Aloysius Tabor was an American political activist and member of the Black Panther Party who was charged and tried as part of an alleged conspiracy to bomb public buildings in New York City and kill members of the New York Police Department.

Donald Lee Cox, known as Field Marshal DC, was an early member of the leadership of the African American revolutionary leftist organization the Black Panther Party, joining the group in 1967. Cox was titled the Field Marshal of the group during the years he actively participated in its leadership, due to his familiarity with and writing about guns.

Ericka Huggins is an American activist, writer, and educator. She is a former leading member of the political organization, Black Panther Party (BPP). She was married to fellow BPP member John Huggins in 1968.

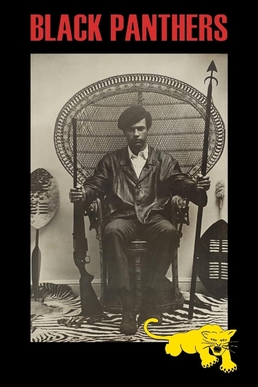

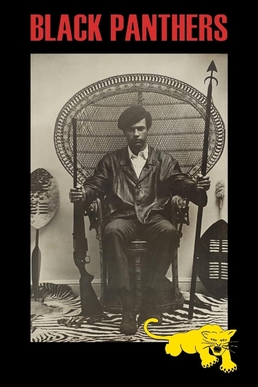

Black Panthers is a 1968 short documentary film directed by Agnès Varda.

Seize The Time: The Story of The Black Panther Party and Huey P. Newton is a 1970 book by political activist Bobby Seale. It was recorded in San Francisco County Jail between November 1969 and March 1970, by Arthur Goldberg, a reporter for the San Francisco Bay Guardian. An advocacy book on the cause and principles of the Black Panther Party, Seize The Time is considered a staple in Black Power literature.

The Revolutionary People's Communication Network was an organization created in 1971 by Kathleen Cleaver and Eldridge Cleaver and their allies after the Cleavers' expulsion from the Black Panther Party while the Cleavers were living in Algeria. It included subgroups such as the Black Liberation Front.

Constance Evadine Matthews, better known as Connie Matthews, was an organizer, a part of the Black Panther Party between 1968 and 1971. A resident of Denmark, she helped co-ordinate the Black Panthers with left-wing political groups based in Europe.