The civil rights movement was a social movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized racial segregation, discrimination, and disenfranchisement in the country. The movement had its origins in the Reconstruction era during the late 19th century and had its modern roots in the 1940s, although the movement made its largest legislative gains in the 1960s after years of direct actions and grassroots protests. The social movement's major nonviolent resistance and civil disobedience campaigns eventually secured new protections in federal law for the civil rights of all Americans.

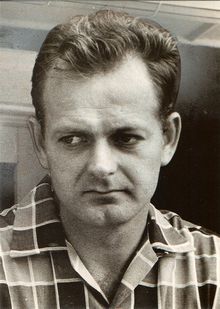

Andrew Goodman was an American civil rights activist. He was one of three Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) workers murdered in Philadelphia, Mississippi, by members of the Ku Klux Klan in 1964. Goodman and two fellow activists, James Chaney and Michael Schwerner, were volunteers for the Freedom Summer campaign that sought to register African-Americans to vote in Mississippi and to set up Freedom Schools for black Southerners.

The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee was the principal channel of student commitment in the United States to the civil rights movement during the 1960s. Emerging in 1960 from the student-led sit-ins at segregated lunch counters in Greensboro, North Carolina, and Nashville, Tennessee, the Committee sought to coordinate and assist direct-action challenges to the civic segregation and political exclusion of African Americans. From 1962, with the support of the Voter Education Project, SNCC committed to the registration and mobilization of black voters in the Deep South. Affiliates such as the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party and the Lowndes County Freedom Organization in Alabama also worked to increase the pressure on federal and state government to enforce constitutional protections.

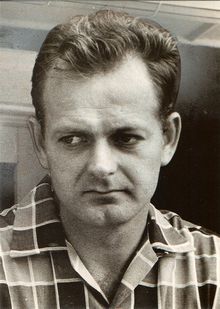

Michael Henry Schwerner was an American civil rights activist. He was one of three Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) field workers killed in rural Neshoba County, Mississippi, by members of the Ku Klux Klan. Schwerner and two co-workers, James Chaney and Andrew Goodman, were killed in response to their civil rights work, which included promoting voting registration among African Americans, most of whom had been disenfranchised in the state since 1890.

The Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP), also referred to simply as the Freedom Democratic Party, was an American political party that existed in the state of Mississippi from 1964 to 1968, during the Civil Rights Movement. Created as the partisan political branch of the Freedom Democratic organization, the party was organized by African Americans and White Americans sympathetic to the Civil Rights Movement from Mississippi to challenge the established power of the state Mississippi Democratic Party, which at the time opposed the Civil Rights Movement and allowed participation only by Whites, despite the fact that African Americans made up 40% of the state population.

Freedom Summer, also known as the Freedom Summer Project or the Mississippi Summer Project, was a volunteer campaign in the United States launched in June 1964 to attempt to register as many African-American voters as possible in Mississippi. Blacks had been restricted from voting since the turn of the century due to barriers to voter registration and other laws. The project also set up dozens of Freedom Schools, Freedom Houses, and community centers such as libraries, in small towns throughout Mississippi to aid the local Black population.

The Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) is an African-American civil rights organization based in Atlanta, Georgia. SCLC is closely associated with its first president, Martin Luther King Jr., who had a large role in the American civil rights movement.

The Selma to Montgomery marches were three protest marches, held in 1965, along the 54-mile (87 km) highway from Selma, Alabama, to the state capital of Montgomery. The marches were organized by nonviolent activists to demonstrate the desire of African-American citizens to exercise their constitutional right to vote, in defiance of segregationist repression; they were part of a broader voting rights movement underway in Selma and throughout the American South. By highlighting racial injustice, they contributed to passage that year of the Voting Rights Act, a landmark federal achievement of the civil rights movement.

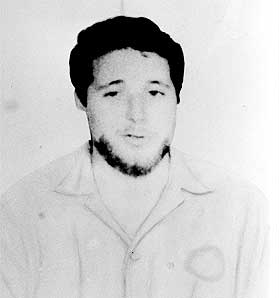

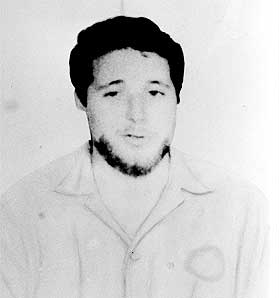

James Earl Chaney was an American civil rights activist. He was one of three Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) civil rights workers killed in Philadelphia, Mississippi, by members of the Ku Klux Klan on June 21, 1964. The others were Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner from New York City.

William Lewis Moore was a postal worker and Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) member who staged lone protests against racial segregation. He was assassinated in Keener, Alabama, during a protest march from Chattanooga, Tennessee to Jackson, Mississippi, where he intended to deliver a letter to Governor Ross Barnett, supporting civil rights.

Robert Parris Moses was an American educator and civil rights activist known for his work as a leader of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) on voter education and registration in Mississippi during the Civil Rights Movement, and his co-founding of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party. As part of his work with the Council of Federated Organizations (COFO), a coalition of the Mississippi branches of the four major civil rights organizations, he was the main organizer for the Freedom Summer Project.

The Council of Federated Organizations (COFO) was a coalition of the major Civil Rights Movement organizations operating in Mississippi. COFO was formed in 1961 to coordinate and unite voter registration and other civil rights activities in the state and oversee the distribution of funds from the Voter Education Project. It was instrumental in forming the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party. COFO member organizations included the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

George Raymond Jr. was an African-American civil rights activist, a member of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, a Freedom Rider, and head of the Congress of Racial Equality in Mississippi in the 1960s. Raymond influenced many of Mississippi's most known activists, such as Anne Moody, C. O. Chinn, and Annie Devine to join the movement and was influential in many of Mississippi's most notable Civil Rights activities such as a Woolworth's lunchcounter sit-in and protests in Jackson, Mississippi, Meredith Mississippi March, and Freedom Summer. Raymond fought for voting rights and equality for African Americans within society amongst other things.

Charles E. "Charlie" Cobb Jr. is a journalist, professor, and former activist with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). Along with several veterans of SNCC, Cobb established and operated the African-American bookstore Drum and Spear in Washington, D.C., from 1968 to 1974. Currently he is a senior analyst at allAfrica.com and a visiting professor at Brown University.

The history of the 1954 to 1968 American civil rights movement has been depicted and documented in film, song, theater, television, and the visual arts. These presentations add to and maintain cultural awareness and understanding of the goals, tactics, and accomplishments of the people who organized and participated in this nonviolent movement.

Samuel Leamon Younge Jr. was a civil rights and voting rights activist who was murdered for trying to desegregate a "whites only" restroom. Younge was an enlisted service member in the United States Navy, where he served for two years before being medically discharged. Younge was an active member of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and a leader of the Tuskegee Institute Advancement League.

This is a timeline of the civil rights movement in the United States, a nonviolent mid-20th century freedom movement to gain legal equality and the enforcement of constitutional rights for people of color. The goals of the movement included securing equal protection under the law, ending legally institutionalized racial discrimination, and gaining equal access to public facilities, education reform, fair housing, and the ability to vote.

David J. Dennis is a civil rights activist whose involvement began in the early 1960s. Dennis grew up in the segregated area of Omega, Louisiana. He worked as co-director of the Council of Federated Organizations (COFO), as director of Mississippi's Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), and as one of the organizers of the Mississippi Freedom Summer of 1964. Dennis worked closely with both Bob Moses and Medgar Evers as well as with members of SNCC, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. His first involvement in the Civil Rights Movement was at a Woolworth sit-in organized by CORE and he went on to become a Freedom Rider in 1961. Since 1989, Dennis has put his activism toward the Algebra Project, a nonprofit organization run by Bob Moses that aims to improve mathematics education for minority children. Dennis also speaks publicly about his experiences in the movement through an organization called Dave Dennis Connections.

Curtis Muhammad is an American civil rights activist. Muhammad was an organizer in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) from 1961 to 1968 and later moved on to other activist organizations.

Son of the South is a 2020 American biographical historical drama film, written and directed by Barry Alexander Brown. Based on Bob Zellner's autobiography, The Wrong Side of Murder Creek: A White Southerner in the Freedom Movement, it stars Lucas Till, Lex Scott Davis, Lucy Hale, Jake Abel, Shamier Anderson, Julia Ormond, Cedric the Entertainer and Brian Dennehy in his final film role. Spike Lee serves as an executive producer.