Martin Luther King Jr. was an American Christian minister, activist, and political philosopher who was one of the most prominent leaders in the civil rights movement from 1955 until his assassination in 1968. A black church leader and a son of early civil rights activist and minister Martin Luther King Sr., King advanced civil rights for people of color in the United States through the use of nonviolent resistance and nonviolent civil disobedience against Jim Crow laws and other forms of legalized discrimination.

The civil rights movement was a social movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized racial segregation, discrimination, and disenfranchisement in the country. The movement had its origins in the Reconstruction era during the late 19th century and had its modern roots in the 1940s, although the movement made its largest legislative gains in the 1960s after years of direct actions and grassroots protests. The social movement's major nonviolent resistance and civil disobedience campaigns eventually secured new protections in federal law for the civil rights of all Americans.

The Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) is an African-American civil rights organization in the United States that played a pivotal role for African Americans in the civil rights movement. Founded in 1942, its stated mission is "to bring about equality for all people regardless of race, creed, sex, age, disability, sexual orientation, religion or ethnic background." To combat discriminatory policies regarding interstate travel, CORE participated in Freedom Rides as college students boarded Greyhound Buses headed for the Deep South. As the influence of the organization grew, so did the number of chapters, eventually expanding all over the country. Despite CORE remaining an active part of the fight for change, some people have noted the lack of organization and functional leadership has led to a decline of participation in social justice.

The Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) is an African-American civil rights organization based in Atlanta, Georgia. SCLC is closely associated with its first president, Martin Luther King Jr., who had a large role in the American civil rights movement.

Bill Moyer was a United States social change activist who was a principal organizer in the 1966 Chicago Open Housing Movement. He was an author, and a founding member of the Movement for a New Society.

The Selma to Montgomery marches were three protest marches, held in 1965, along the 54-mile (87 km) highway from Selma, Alabama, to the state capital of Montgomery. The marches were organized by nonviolent activists to demonstrate the desire of African-American citizens to exercise their constitutional right to vote, in defiance of segregationist repression; they were part of a broader voting rights movement underway in Selma and throughout the American South. By highlighting racial injustice, they contributed to passage that year of the Voting Rights Act, a landmark federal achievement of the civil rights movement.

The March Against Fear was a major 1966 demonstration in the Civil Rights Movement in the South. Activist James Meredith launched the event on June 5, 1966, intending to make a solitary walk from Memphis, Tennessee, to Jackson, Mississippi via the Mississippi Delta, starting at Memphis's Peabody Hotel and proceeding to the Mississippi state line, then continuing through, respectively, the Mississippi cities of Hernando, Grenada, Greenwood, Indianola, Belzoni, Yazoo City, and Canton before arriving at Jackson's City Hall. The total distance marched was approximately 270 miles over a period of 21 days. The goal was to counter the continuing racism in the Mississippi Delta after passage of federal civil rights legislation in the previous two years and to encourage African Americans in the state to register to vote. He invited only individual black men to join him and did not want it to be a large media event dominated by major civil rights organizations.

James Forman was a prominent African-American leader in the civil rights movement. He was active in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), the Black Panther Party, and the League of Revolutionary Black Workers. As the executive secretary of SNCC from 1961 to 1966, Forman played a significant role in the Freedom Rides, the Albany movement, the Birmingham campaign, and the Selma to Montgomery marches.

Freddie Lee Shuttlesworth was an American civil rights activist who led the fight against segregation and other forms of racism as a minister in Birmingham, Alabama. He was a co-founder of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, initiated and was instrumental in the 1963 Birmingham Campaign, and continued to work against racism and for alleviation of the problems of the homeless in Cincinnati, Ohio, where he took up a pastorate in 1961. He returned to Birmingham after his retirement in 2007. He worked with Martin Luther King Jr. during the civil rights movement, though the two men often disagreed on tactics and approaches.

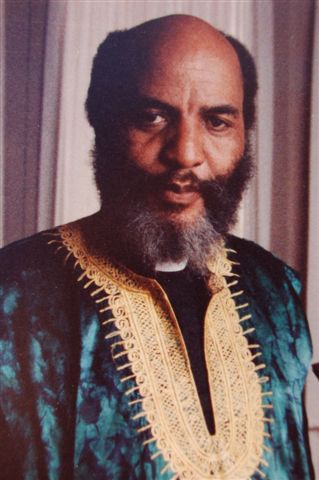

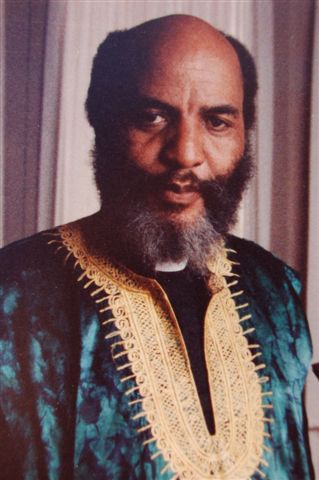

Wyatt Tee Walker was an African-American pastor, national civil rights leader, theologian, and cultural historian. He was a chief of staff for Martin Luther King Jr., and in 1958 became an early board member of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). He helped found a Congress for Racial Equality (CORE) chapter in 1958. As executive director of the SCLC from 1960 to 1964, Walker helped to bring the group to national prominence. Walker sat at the feet of his mentor, BG Crawley, who was a Baptist Minister in Brooklyn, NY and New York State Judge.

Diane Judith Nash is an American civil rights activist, and a leader and strategist of the student wing of the Civil Rights Movement.

Operation Breadbasket was an organization dedicated to improving the economic conditions of black communities across the United States. Operation Breadbasket was launched on February 11, 1966, under the leadership of Jesse Jackson. Its primary objective was to promote the employment of African Americans by companies operating in black communities and support the growth of black-owned businesses. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. described the core principle of Breadbasket as the belief that African Americans should not support businesses that denied them job opportunities, career advancement, or basic courtesy. To achieve their goals, the activists of Operation Breadbasket adopted a strategy called "selective patronage." They focused their initial campaign on dairy companies and supermarket chains. They organized pickets and encouraged boycotts of stores that carried products from the targeted companies, aiming to pressure them into improving their employment practices and support for the black community.

The Birmingham campaign, also known as the Birmingham movement or Birmingham confrontation, was an American movement organized in early 1963 by the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) to bring attention to the integration efforts of African Americans in Birmingham, Alabama.

James Luther Bevel was an American minister and leader of the 1960s Civil Rights Movement in the United States. As a member of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), and then as its Director of Direct Action and Nonviolent Education, Bevel initiated, strategized, and developed SCLC's three major successes of the era: the 1963 Birmingham Children's Crusade, the 1965 Selma voting rights movement, and the 1966 Chicago open housing movement. He suggested that SCLC call for and join a March on Washington in 1963. Bevel strategized the 1965 Selma to Montgomery marches, which contributed to Congressional passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

Cordy Tindell Vivian was an American minister, author, and close friend and lieutenant of Martin Luther King Jr. during the civil rights movement. Vivian resided in Atlanta, Georgia, and founded the C. T. Vivian Leadership Institute, Inc. He was a member of the Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity.

Bernard Lafayette, Jr. is an American civil rights activist and organizer, who was a leader in the Civil Rights Movement. He played a leading role in early organizing of the Selma Voting Rights Movement; was a member of the Nashville Student Movement; and worked closely throughout the 1960s movements with groups such as the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), and the American Friends Service Committee.

The Summer Community Organization and Political Education (SCOPE) Project of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) was a voter registration civil rights initiative conducted from 1965 to 1966 in 120 counties in six southern states. The goal was to recruit white college students to help prepare African Americans for voting and to maintain pressure on Congress to pass what became the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Dr. Martin Luther King announced the project at UCLA in April 1965, and other leaders recruited students nationwide.

The St. Augustine movement was a part of the wider Civil Rights Movement, taking place in St. Augustine, Florida from 1963 to 1964. It was a major event in the city's long history and had a role in the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Cicero March is a 1966 short documentary film made by the Chicago-based production company, The Film Group. The film details a civil rights march held on September 4, 1966, in Cicero, Illinois.

This is a timeline of the civil rights movement in the United States, a nonviolent mid-20th century freedom movement to gain legal equality and the enforcement of constitutional rights for people of color. The goals of the movement included securing equal protection under the law, ending legally institutionalized racial discrimination, and gaining equal access to public facilities, education reform, fair housing, and the ability to vote.