Vanport, sometimes referred to as Vanport City or Kaiserville, was a city of wartime public housing in Multnomah County, Oregon, United States, between the contemporary Portland city boundary and the Columbia River. It was destroyed in the 1948 Columbia River flood and not rebuilt. It sat on what is currently the site of Delta Park and the Portland International Raceway.

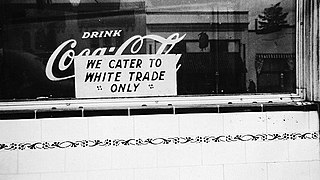

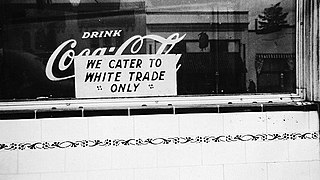

Sundown towns, also known as sunset towns, gray towns, or sundowner towns, are all-white municipalities or neighborhoods in the United States and Canada that were most prevalent before the mid-20th century, which practiced a form of racial segregation by excluding non-whites via some combination of discriminatory local laws, intimidation or violence. The term came into use because of signs that directed "colored people" to leave town by sundown.

Racism has been reflected in discriminatory laws, practices, and actions against "racial" or ethnic groups throughout the history of the United States. Since the early colonial era, White Americans have generally enjoyed legally or socially sanctioned privileges and rights which have been denied to members of various ethnic or minority groups at various times. European Americans have enjoyed advantages in matters of education, immigration, voting rights, citizenship, land acquisition, and criminal procedure.

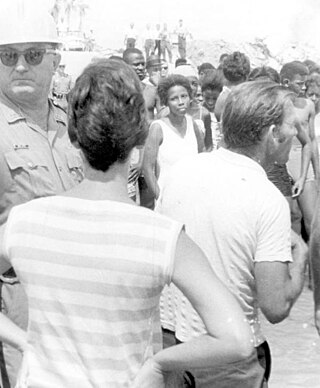

The nadir of American race relations was the period in African-American history and the history of the United States from the end of Reconstruction in 1877 through the early 20th century, when racism in the country, especially anti-black racism, was more open and pronounced than it had ever been during any other period in the nation's history. During this period, African Americans lost access to many of the civil rights which they had gained during Reconstruction. Anti-black violence, lynchings, segregation, legalized racial discrimination, and expressions of white supremacy all increased. Asian Americans were also not spared from such sentiments.

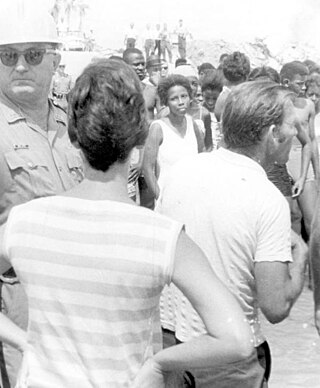

Facilities and services such as housing, healthcare, education, employment, and transportation have been systematically separated in the United States based on racial categorizations. Segregation was the legally or socially enforced separation of African Americans from whites, as well as the separation of other ethnic minorities from majority and mainstream communities. While mainly referring to the physical separation and provision of separate facilities, it can also refer to other manifestations such as prohibitions against interracial marriage, and the separation of roles within an institution. The U.S. Armed Forces were formally segregated until 1948, as black units were separated from white units but were still typically led by white officers.

In the context of the 20th-century history of the United States, the Second Great Migration was the migration of more than 5 million African Americans from the South to the Northeast, Midwest and West. It began in 1940, through World War II, and lasted until 1970. It was much larger and of a different character than the first Great Migration (1916–1940), where the migrants were mainly rural farmers from the South and only came to the Northeast and Midwest.

Legislation seeking to direct relations between racial or ethnic groups in the United States has had several historical phases, developing from the European colonization of the Americas, the triangular slave trade, and the American Indian Wars. The 1776 Declaration of Independence included the statement that "all men are created equal", which has ultimately inspired actions and legislation against slavery and racial discrimination. Such actions have led to passage of the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments to the Constitution of the United States.

African-American neighborhoods or black neighborhoods are types of ethnic enclaves found in many cities in the United States. Generally, an African American neighborhood is one where the majority of the people who live there are African American. Some of the earliest African-American neighborhoods were in New Orleans, Mobile, Atlanta, and other cities throughout the American South, as well as in New York City. In 1830, there were 14,000 "Free negroes" living in New York City.

The sociology of race and ethnic relations is the study of social, political, and economic relations between races and ethnicities at all levels of society. This area encompasses the study of systemic racism, like residential segregation and other complex social processes between different racial and ethnic groups.

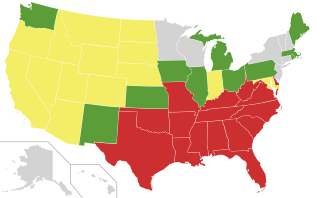

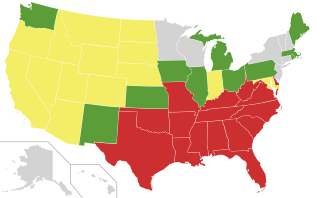

In the United States, many U.S. states historically had anti-miscegenation laws which prohibited interracial marriage and, in some states, interracial sexual relations. Some of these laws predated the establishment of the United States, and some dated to the later 17th or early 18th century, a century or more after the complete racialization of slavery. Nine states never enacted anti-miscegenation laws, and 25 states had repealed their laws by 1967. In that year, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Loving v. Virginia that such laws are unconstitutional under the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

In the United States, racial inequality refers to the social inequality and advantages and disparities that affect different races. These can also be seen as a result of historic oppression, inequality of inheritance, or racism and prejudice, especially against minority groups.

The Oregon black exclusion laws were attempts to prevent black people from settling within the borders of the settlement and eventual U.S. state of Oregon. The first such law took effect in 1844, when the Provisional Government of Oregon voted to exclude black settlers from Oregon's borders. The law authorized a punishment for any black settler remaining in the territory to be whipped with "not less than twenty nor more than thirty-nine stripes" for every six months they remained. Additional laws aimed at African Americans entering Oregon were ratified in 1849 and 1857. The last of these laws was repealed in 1926. The laws, born of pro-slavery and anti-black beliefs, were often justified as a reaction to fears of black people instigating Native American uprisings.

The history of racism in Oregon began before the territory even became a U.S. state. The topic of race was heavily discussed during the convention where the Oregon Constitution was written in 1857. In 1859, Oregon became the only state to enter the Union with a black exclusion law, although there were many other states that had tried before, especially in the Midwest. The Willamette Valley was notorious for hosting white supremacist hate groups. Discrimination and segregation were common occurrences against people of Indigenous, African, Mexican, Hawaiian, and Asian descent. Portland, the largest city in the state, continues to have one of the largest proportions of white residents of major U.S. cities.

Ghettos in the United States are typically urban neighborhoods perceived as being high in crime and poverty. The origins of these areas are specific to the United States and its laws, which created ghettos through both legislation and private efforts to segregate America for political, economic, social, and ideological reasons: de jure and de facto segregation. De facto segregation continues today in ways such as residential segregation and school segregation because of contemporary behavior and the historical legacy of de jure segregation.

The Urban League of Portland is a service, civil rights, and advocacy organization for African Americans in the Pacific Northwest region. Today, the League is a non-profit, community-based organization committed to providing opportunities and support services for education, employment, health, economic security, and quality of life.

Albina is a collection of neighborhoods located in the North and Northeast sections of Portland, Oregon, United States. For most of the 20th century it was home to the majority of the city’s African American population. The area derives its name from Albina, Oregon, a historical American city that was consolidated into Portland in 1891. Albina includes the modern Portland neighborhoods of Eliot, Boise, Humboldt, Overlook, and Piedmont.

Home Forward, established in 1941 as the Housing Authority of Portland, is a housing authority that serves Portland, Oregon, and nearby municipalities in Multnomah County, Oregon, United States. Home Forward maintains properties in Portland, Gresham, and Fairview.

The Ku Klux Klan (KKK) arrived in the U.S. state of Oregon in the early 1920s, during the history of the second Klan, and it quickly spread throughout the state, aided by a mostly white, Protestant population as well as by racist and anti-immigrant sentiments which were already embedded in the region. The Klan succeeded in electing its members in local and state governments, which allowed it to pass legislation that furthered its agenda. Ultimately, the struggles and decline of the Klan in Oregon coincided with the struggles and decline of the Klan in other states, and its activity faded in the 1930s.

In the context of racism in the United States, racism against African Americans dates back to the colonial era, and it continues to be a persistent issue in American society in the 21st century.

According to the City of Portland, "In all categories, the Eastside is more racially diverse than the Westside. Hispanics are most concentrated in North Portland at nearly 15% of the population. NE Portland has the highest concentration of African Americans at 30%. The concentration of Asians in Portland are mostly within NE, SE, and outer East Portland, with a percent population of 11%, 10%, and 9% respectively. Whites are the most common race group citywide."