The Aztecs were a Mesoamerican culture that flourished in central Mexico in the post-classic period from 1300 to 1521. The Aztec people included different ethnic groups of central Mexico, particularly those groups who spoke the Nahuatl language and who dominated large parts of Mesoamerica from the 14th to the 16th centuries. Aztec culture was organized into city-states (altepetl), some of which joined to form alliances, political confederations, or empires. The Aztec Empire was a confederation of three city-states established in 1427: Tenochtitlan, city-state of the Mexica or Tenochca, Texcoco, and Tlacopan, previously part of the Tepanec empire, whose dominant power was Azcapotzalco. Although, the term Aztecs is often narrowly restricted to the Mexica of Tenochtitlan, it is also broadly used to refer to Nahua polities or peoples of central Mexico in the prehispanic era, as well as the Spanish colonial era (1521–1821). The definitions of Aztec and Aztecs have long been the topic of scholarly discussion ever since German scientist Alexander von Humboldt established its common usage in the early 19th century.

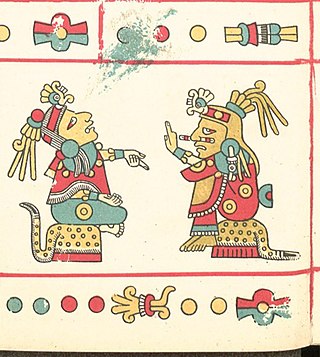

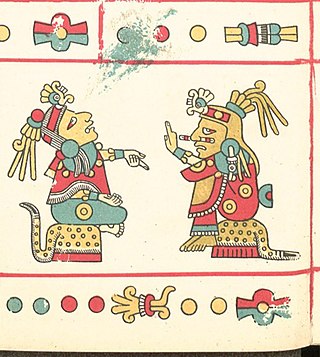

Ōmeteōtl is a name used to refer to the pair of Aztec deities Ometecuhtli and Omecihuatl, also known as Tōnacātēcuhtli and Tonacacihuatl. Ōme translates as "two" or "dual" in Nahuatl and teōtl translates as "god". The existence of such a concept and its significance is a matter of dispute among scholars of Mesoamerican religion. Ometeotl was one as the first divinity, and Ometecuhtli and Omecihuatl when the being became two to be able to reproduce all creation

In Aztec mythology, Tloquenahuaque, Tloque Nahuaque or Tloque Naoaque was one of the epithets of Tezcatlipoca. Miguel Leon Portilla argues that Tloque Nahuaque was also used as an epithet of Ometeotl, the hypothetical duality creator God of the Aztecs. Tloquenahuaque, also referred to as Tloque Nahuaque or Tloque Naoaque, is a creator god in Aztec mythology. Meso-Americans knew this god by other names as well, "Moyocoyani or Hunab Ku".

In Aztec mythology, Tōnacācihuātl was a creator and goddess of fertility, worshiped for peopling the earth and making it fruitful. Most Colonial-era manuscripts equate her with Ōmecihuātl. Tōnacācihuātl was the consort of Tōnacātēcuhtli. She is also referred to as Ilhuicacihuātl or "Heavenly Lady."

Miguel León-Portilla was a Mexican anthropologist and historian, specializing in Aztec culture and literature of the pre-Columbian and colonial eras. Many of his works were translated to English and he was a well-recognized scholar internationally. In 2013, the Library of Congress of the United States bestowed on him the Living Legend Award.

Tlacaelel I was the principal architect of the Aztec Triple Alliance and hence the Mexica (Aztec) empire. He was the son of Emperor Huitzilihuitl and Queen Cacamacihuatl, nephew of Emperor Itzcoatl, father of poet Macuilxochitzin, and brother of Emperors Chimalpopoca and Moctezuma I.

The Aztec Empire or the Triple Alliance was an alliance of three Nahua city-states: Mexico-Tenochtitlan, Tetzcoco, and Tlacopan. These three city-states ruled that area in and around the Valley of Mexico from 1428 until the combined forces of the Spanish conquistadores and their native allies who ruled under Hernán Cortés defeated them in 1521.

Diego Durán was a Dominican friar best known for his authorship of one of the earliest Western books on the history and culture of the Aztecs, The History of the Indies of New Spain, a book that was much criticised in his lifetime for helping the "heathen" maintain their culture.

The Calmecac was a school for the sons of Aztec nobility in the Late Postclassic period of Mesoamerican history, where they would receive rigorous training in history, calendars, astronomy, religion, economy, law, ethics and warfare. The two main primary sources for information on the calmecac and telpochcalli are in Bernardino de Sahagún's Florentine Codex of the General History of the Things of New Spain and part 3 of the Codex Mendoza.

The Aztec religion is a polytheistic and monistic pantheism in which the Nahua concept of teotl was construed as the supreme god Ometeotl, as well as a diverse pantheon of lesser gods and manifestations of nature. The popular religion tended to embrace the mythological and polytheistic aspects, and the Aztec Empire's state religion sponsored both the monism of the upper classes and the popular heterodoxies.

The Anales de Tlatelolco is a codex manuscript written in Nahuatl, using Latin characters, by anonymous Aztec authors. The text has no pictorial content. Although there is an assertion that the text was a copy of one written in 1528 in Tlatelolco, only seven years after the fall of the Aztec Empire, James Lockhart argues that there is no evidence for this early date of composition, based on internal evidence of the text. However, he supports the contention that this is an authentic conquest account, arguing that it was composed about 20 years after the conquest in the 1540s, and contemporaneous with the Cuernavaca censuses. Unlike the Florentine Codex and its account of the conquest of the Aztec Empire, the Annals of Tlatelolco remained in Nahua hands, providing authentic insight into the thoughts and outlook of the newly conquered Nahuas.

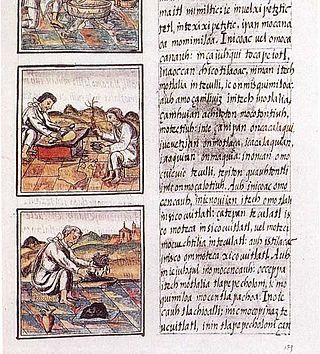

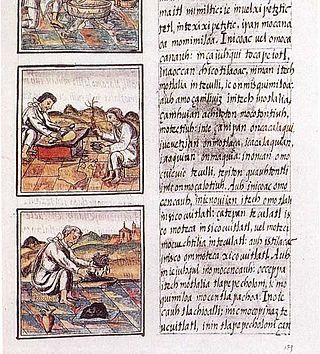

The Florentine Codex is a 16th-century ethnographic research study in Mesoamerica by the Spanish Franciscan friar Bernardino de Sahagún. Sahagún originally titled it: La Historia General de las Cosas de Nueva España. After a translation mistake, it was given the name Historia general de las Cosas de Nueva España. The best-preserved manuscript is commonly referred to as the Florentine Codex, as the codex is held in the Laurentian Library of Florence, Italy.

Tlamatini is a Nahuatl language word meaning "someone who knows something", generally translated as "wise man". The word is analyzable as derived from the transitive verb mati "to know" with the prefix tla- indicating an unspecified inanimate object translatable by "something" and the derivational suffix -ni meaning "a person who is characterized by ...": hence tla-mati-ni "a person who is characterized by knowing something" or more to the point "a knower".

Teōtl is a Nahuatl term for sacredness or divinity that is sometimes translated as "god". For the Aztecs teotl was the metaphysical omnipresence upon which their religious philosophy was based.

Difrasismo is a term derived from Spanish that is used in the study of certain Mesoamerican languages, to describe a particular grammatical construction in which two separate words are paired together to form a single metaphoric unit. This semantic and stylistic device was commonly employed throughout Mesoamerica, and features notably in historical works of Mesoamerican literature, in languages such as Classical Nahuatl and Classic Maya.

The Cantares Mexicanos is the name given to a manuscript collection of Nahuatl songs or poems recorded in the 16th century. The 91 songs of the Cantares form the largest Nahuatl song collection, containing over half of all known traditional Nahuatl songs. It is currently located in the National Library of Mexico in Mexico City. A description is found in the census of prose manuscripts in the native tradition in the Handbook of Middle American Indians.

New Philology generally refers to a branch of Mexican ethnohistory and philology that uses colonial-era native language texts written by Indians to construct history from the indigenous point of view. The name New Philology was coined by James Lockhart to describe work that he and his doctoral students and scholarly collaborators in history, anthropology, and linguistics had pursued since the mid-1970s. Lockhart published a great many essays elaborating on the concept and content of the New Philology and Matthew Restall published a description of it in the Latin American Research Review.

Dialectical monism, also known as dualistic monism or monistic dualism, is an ontological position that holds that reality is ultimately a unified whole, distinguishing itself from monism by asserting that this whole necessarily expresses itself in dualistic terms.

Indigenous American philosophy is the philosophy of the Indigenous peoples of the Americas. An Indigenous philosopher is an Indigenous American person who practices philosophy and has a vast knowledge of history, culture, language, and traditions of the Indigenous peoples of the Americas. Many different traditions of philosophy exist in the Americas, and have from Precolumbian times.

Omeyocan is the highest of thirteen heavens in Aztec mythology, the dwelling place of Ometeotl, the dual god comprising Ometecuhtli and Omecihuatl.