Influence on Dutch philosophy

Thought of Desiderius Erasmus

Desiderius Erasmus's influence on Dutch philosophy is marked by his contributions to the discourse of Christian humanism, which highlights a philosophy that synthesises the humanistic perspective of self-determination with classical Christian traditions of virtue. [7] At the core of his philosophical teachings, Erasmus promulgated the religious doctrine of docta pietas (English: learned piety), which Erasmus believed was the 'Philosophy of Christ'. [7] Erasmus, further expanded upon this notion in Julius Excluded from Heaven (Latin: Julius exclusus e coelis), as cited in The Erasmus Reader where:

"Our great master did not come down from heaven to earth to give men some easy or common philosophy. It is not a carefree or tranquil profession to be a Christian." [8]

Erasmus also wrote a large collection of ten critical essays titled Opera Omnia, which explore critical views on topics that range from education on the philosophy of Christian humanism in the Dutch Republic to his personal translation of the New Testament that consisted of his humanistic-influenced annotations. [9] [10] He grounded these annotations through extensive readings of Church Fathers writings. [11] Erasmus further commented in Enchiridion militis Christiani (Latin: Handbook of a Christian Knight) that the readings can equip people with a more advanced understanding of Christian humanism. [12] The book was written in order to highlight the divergence of theological education from classical antiquity, which incorporated a philosophy on morals and ethics, practised in the Dutch Republic during the 16th century. [11] [12] Erasmus further argued that detailed knowledge of classical antiquity would correspond to people having greater knowledge of the 'Philosophy of Christ' and therefore, have some knowledge of Christian humanistic philosophy. [13]

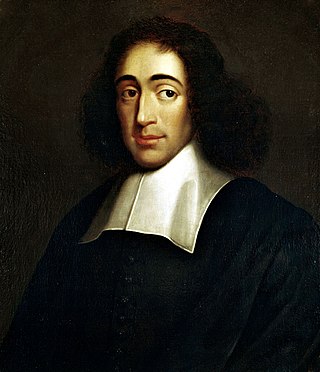

Thought of Baruch Spinoza

The development of Dutch philosophy was one that expounded the fallacy behind God's metaphysical nature and in general, God's existence. These fallacies are attributed to the writings of Baruch Spinoza. [14] With lacking affiliations to any religious institution and university, a direct consequence of being excommunicated by his local Sephardic community in Amsterdam for the aforementioned views, Spinoza pursued his philosophical studies with a degree of independence. [15] Spinoza's philosophical works, the Tractatus Theologico-Politicus (also referred to as the Theologico-Political Treatise), which was Spinoza's only work published during his lifetime, contributed to his influence on Dutch philosophy. [16] The Theologico-Political Treatise discusses the relevance of Calvinist theology in the Dutch Republic by commenting how the Bible should be interpreted exclusively on its own terms by extracting information about the Bible from only what is directly evident in the text. Spinoza also raised the need to avoid the formulation of hypotheticals about what the Bible may assume, referred to as his hermeneutic principle. [17] Additionally, in this work, Spinoza advocated for the practice of libertas philosophandi ( Latin: freedom to philosophise) which emphasises the importance of philosophy that is void of any external religious or political constraint. [18]

Ethics —published after his death—garnered Spinoza scholarly attention, as he was one of the first Dutch philosophers during the Renaissance period that gave criticism to long-standing perspectives on God, the universe, nature and the ethical principles that grounded them. [19] Spinoza incorporated metaphysical and anthropological conceptions to support his conclusions. [20] This work, together with others, led to Spinoza being ostracised from the Jewish community in Amsterdam because he devalued the commonly held belief that God should not be "feign a God, like man, consisting of a body and mind, and subject to passions." [21]

Spinoza further extended this belief in his Propositions in Ethics by commenting on the nature of human desire as one that is interrelated with the mind's pathema (Ancient Greek: passions). [22] In conjunction, the human desire and pathema contributed to what Spinoza argued was an affect of the human body, which grant humans the capability to achieve some state of perfection. [23] [24] Modern Dutch philosopher Theo Verbeek further comments that Spinoza's commentaries on the affect, in addition to the practice of libertas philosophandi, contributed to Renaissance Dutch philosophy. [25]