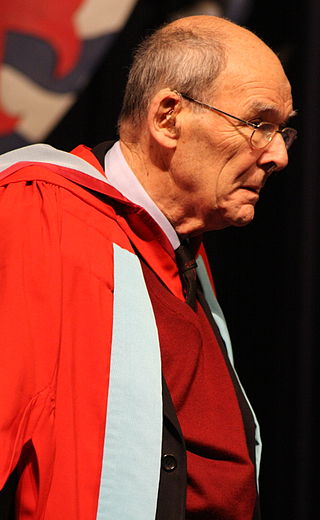

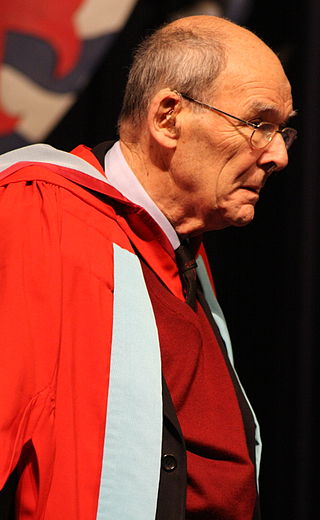

John Leslie Mackie was an Australian philosopher. He made significant contributions to the philosophy of religion, metaphysics, and the philosophy of language.

Mary Rosalind Hursthouse is a British-born New Zealand moral philosopher noted for her work on virtue ethics. Hursthouse is Professor Emerita of Philosophy at the University of Auckland.

John Jamieson Carswell Smart, was a British-Australian philosopher and was appointed as an Emeritus Professor by the Australian National University. He worked in the fields of metaphysics, philosophy of science, philosophy of mind, philosophy of religion, and political philosophy. He wrote multiple entries for the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

The Bruces sketch is a comedy sketch that originally appeared in a 1970 episode of the television show Monty Python's Flying Circus, episode 22, "How to Recognise Different Parts of the Body", and was subsequently performed on audio recordings and live on many occasions by the Monty Python team.

Frank Cameron JacksonFBA is an Australian analytic philosopher and Emeritus Professor in the School of Philosophy at Australian National University (ANU) where he had spent most of the latter part of his career. His primary research interests include epistemology, metaphysics, meta-ethics and the philosophy of mind. In the latter field he is best known for the "Mary's room" knowledge argument, a thought experiment that is one of the most discussed challenges to physicalism.

David Malet Armstrong, often D. M. Armstrong, was an Australian philosopher. He is well known for his work on metaphysics and the philosophy of mind, and for his defence of a factualist ontology, a functionalist theory of the mind, an externalist epistemology, and a necessitarian conception of the laws of nature. He was elected a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2008.

Freya Mathews is an Australian environmental philosopher whose main work has been in the areas of ecological metaphysics and panpsychism. Her current special interests are in ecological civilization; indigenous perspectives on "sustainability" and how these perspectives may be adapted to the context of contemporary global society; panpsychism and critique of the metaphysics of modernity; and wildlife ethics and rewilding in the context of the Anthropocene.

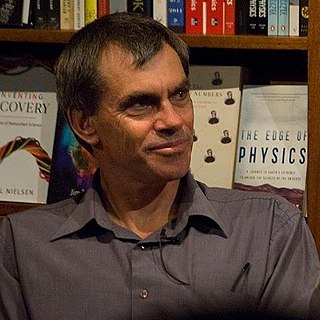

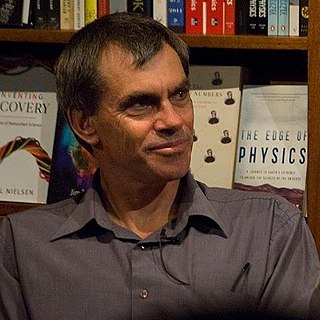

Russell Blackford is an Australian writer, philosopher, and literary critic.

Richard Newell Boyd was an American philosopher, who spent most of his career teaching philosophy at Cornell University where he was Susan Linn Sage Professor of Philosophy and Humane Letters Emeritus. He specialized in epistemology, the philosophy of science, language, and mind.

Graham Robert Oppy is an Australian philosopher whose main area of research is the philosophy of religion. He currently holds the posts of Professor of Philosophy and Associate Dean of Research at Monash University and serves as CEO of the Australasian Association of Philosophy, Chief Editor of the Australasian Philosophical Review, Associate Editor of the Australasian Journal of Philosophy, and serves on the editorial boards of Philo, Philosopher's Compass, Religious Studies, and Sophia. He was elected Fellow of the Australian Academy of the Humanities in 2009.

James Franklin is an Australian philosopher, mathematician and historian of ideas.

Australian realism, also called Australian materialism, is a school of philosophy that flourished in the first half of the 20th century in several universities in Australia including the Australian National University, the University of Adelaide, and the University of Sydney, and whose central claim, as stated by leading theorist John Anderson, was that "whatever exists … is real, that is to say it is a spatial and temporal situation or occurrence that is on the same level of reality as anything else that exists". Coupled with this was Anderson's idea that "every fact is a complex situation: there are no simples, no atomic facts, no objects which cannot be, as it were, expanded into facts." Prominent players included Anderson, David Malet Armstrong, J. L. Mackie, Ullin Place, J. J. C. Smart, and David Stove. The label "Australian realist" was conferred on acolytes of Anderson by A. J. Baker in 1986, to mixed approval from those realist philosophers who happened to be Australian. David Malet Armstrong "suggested, half-seriously, that 'the strong sunlight and harsh brown landscape of Australia force reality upon us'".

Nick Trakakis is an Australian philosopher who is Assistant Director of the Centre for Philosophy and Phenomenology of Religion of the Australian Catholic University. He has previously taught at Monash University and Deakin University, and during 2006–2007 he was a postdoctoral research fellow at the Centre for Philosophy of Religion at the University of Notre Dame. He works mainly at the intersections of philosophy, religion, and theology.

Atheism, in the broadest sense, is an absence of belief in the existence of deities. Less broadly, atheism is a rejection of the belief that any deities exist. In an even narrower sense, atheism is specifically the position that there are no deities. Atheism is contrasted with theism, which in its most general form is the belief that at least one deity exists.

The Australasian Association of Philosophy (AAP) is the peak body for philosophy in Australasia. The chief purpose of the AAP is to promote philosophy in Australia, New Zealand, and Singapore. Among the means that it follows to achieve this end, the AAP runs an annual conference, publishes two journals, awards various prizes, sponsors postgraduate and undergraduate philosophical activities, maintains affiliations with numerous other organisations that aim to promote philosophy and philosophical activity, and promotes philosophy in schools, cafes, pubs, and everywhere else that philosophy may be found.

Charles Leonard Hamblin was an Australian philosopher, logician, and computer pioneer, as well as a professor of philosophy at the New South Wales University of Technology in Sydney.

John Anderson was a Scottish philosopher who occupied the post of Challis Professor of Philosophy at Sydney University from 1927 to 1958. He founded the empirical brand of philosophy known as Australian realism.

Rae Helen Langton, FBA is an Australian-British professor of philosophy. She is currently the Knightbridge Professor of Philosophy at the University of Cambridge. She has published widely on Immanuel Kant's philosophy, moral philosophy, political philosophy, metaphysics, and feminist philosophy. She is also well known for her work on pornography and objectification.

Yujin Nagasawa is a Japanese-born British philosopher specialising in the philosophy of religion, the philosophy of mind and applied philosophy.