Cochise County is a county in the southeastern corner of the U.S. state of Arizona. It is named after Cochise, a Chiricahua Apache who was a key war leader during the Apache Wars.

Bisbee is a city in and the county seat of Cochise County in southeastern Arizona, United States. It is 92 miles (148 km) southeast of Tucson and 11 miles (18 km) north of the Mexican border. According to the 2020 census, the population of the town was 4,923, down from 5,575 in the 2010 census.

Sierra Vista is a city in Cochise County, Arizona, United States. According to the 2020 Census, the population of the city is 45,308, and is the 27th most populous city in Arizona. The city is part of the Sierra Vista-Douglas Metropolitan Area, with a 2010 population of 131,346. Fort Huachuca, a U.S. Army post, has been incorporated and is located in the northwest part of the city. Sierra Vista is bordered by the cities of Huachuca City and Whetstone to the north and Sierra Vista Southeast to the South.

Buffalo Soldiers were United States Army regiments composed primarily of African Americans, formed during the 19th century to serve on the American frontier. On September 21, 1866, the 10th Cavalry Regiment was formed at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. The nickname "Buffalo Soldiers" was purportedly given to the regiment by Native Americans who fought against them in the American Indian Wars, and the term eventually became synonymous with all of the African American U.S. Army regiments established in 1866, including the 9th Cavalry Regiment, 10th Cavalry Regiment, 24th Infantry Regiment, 25th Infantry Regiment and 38th Infantry Regiment.

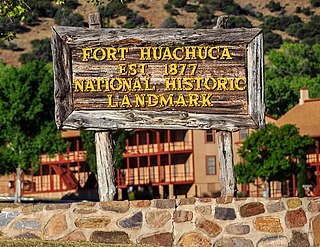

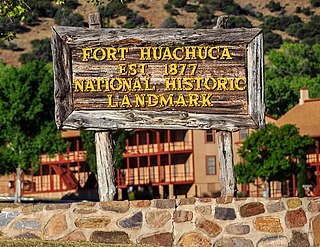

Fort Huachuca is a United States Army installation, established on 3 March 1877 as Camp Huachuca. The garrison is now under the command of the United States Army Installation Management Command. It is in Cochise County in southeast Arizona, approximately 15 miles (24 km) north of the border with Mexico and at the northern end of the Huachuca Mountains, adjacent to the town of Sierra Vista. From 1913 to 1933, the fort was the base for the "Buffalo Soldiers" of the 10th Cavalry Regiment. During the build-up of World War II, the fort had quarters for more than 25,000 male soldiers and hundreds of WACs. In the 2010 census, Fort Huachuca had a population of about 6,500 active duty soldiers, 7,400 military family members, and 5,000 civilian employees. Fort Huachuca has over 18,000 people on post during weekday work hours.

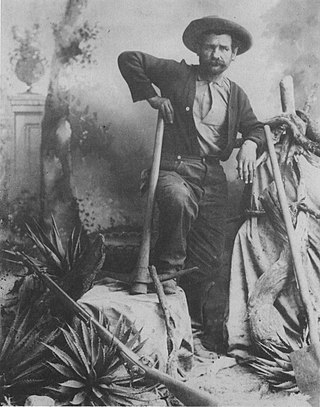

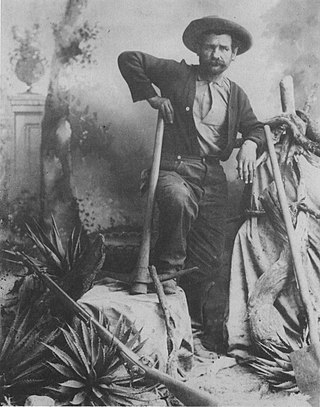

George Warren worked as a prospector in the Tombstone and Bisbee, Arizona region during the late 19th century. He is credited with having located the body of copper ore, which later was known as the Copper Queen Mine, one of Arizona's most productive copper mines. Warren drank too much and bet his interest in the mine on a foot race against a horse and lost.

The Bisbee Deportation was the illegal kidnapping and deportation of about 1,300 striking mine workers, their supporters, and citizen bystanders by 2,000 members of a deputized posse, who arrested them beginning on July 12, 1917, in Bisbee, Arizona. The action was orchestrated by Phelps Dodge, the major mining company in the area, which provided lists of workers and others who were to be arrested to the Cochise County sheriff, Harry C. Wheeler. Those arrested were taken to a local baseball park before being loaded onto cattle cars and deported 200 miles (320 km) to Tres Hermanas in New Mexico. The 16-hour journey was through desert without food and with little water. Once unloaded, the deportees, most without money or transportation, were warned against returning to Bisbee. The US government soon brought in members of the US Army to assist with relocating the deportees to Columbus, New Mexico.

The Cananea strike, also known as the Cananea riot, or the Cananea massacre, took place in the Mexican mining town of Cananea, Sonora, in June 1906. Although the workers were forced to return to their positions with no demand being met, the action was a key event in the general unrest that emerged during the final years of the regime of President Porfirio Díaz and that prefigured the Mexican Revolution of 1910. In the incident, twenty-three people died, on both sides, twenty-two were injured, and more than fifty were arrested.

Fort Naco, Camp Naco, or Fort Newell began as a camp in the Southwest United States, on the outskirts of Naco, Arizona as part of the Mexican Border Project. Over time adobe and wooden buildings were constructed to house the garrison along with other permanent structures.

Harry Cornwall Wheeler was an Arizona lawman who was the third captain of the Arizona Rangers, as well as the sheriff of Cochise County, serving from 1912 into 1918. He is known as the lead figure in the illegal mass kidnapping and deportation of some 1200 miners and family members, many of them immigrants, from Bisbee, Arizona to New Mexico in 1917. Beginning on July 12, 1917, he took total control of the town of Bisbee, controlling access and running kangaroo courts that deported numerous people.

Camillus "Buck" Sydney Fly was an Old West photographer who is regarded by some as an early photojournalist and who captured the only known images of Native Americans while they were still at war with the United States. He took many other pictures of life in the silver-mining boom town of Tombstone, Arizona, and the surrounding region. He recognized the value of his photographs to illustrate periodicals of the day and took his camera to the scenes of important events where he recorded them and resold pictures to editors nationwide.

Cochise County in southeastern Arizona was the scene of a number of violent conflicts in the 19th-century and early 20th-century American Old West, including between white settlers and Apache Indians, between opposing political and economic factions, and between outlaw gangs and local law enforcement. Cochise County was carved off in 1881 from the easternmost portion of Pima County during a formative period in the American Southwest. The era was characterized by rapidly growing boomtowns, the emergence of large-scale farming and ranching interests, lucrative mining operations, and the development of new technologies in railroading and telecommunications. Complicating the situation was staunch resistance to white settlement from local Native American groups, most notably during the Apache Wars, as well as Cochise County's location on the border with Mexico, which not only threatened international conflict but also presented opportunities for criminal smugglers and cattle rustlers.

The Skeleton Canyon shootout was a gunfight on August 12, 1896, between members of the High Five Gang and a posse of American lawmen. Following a failed robbery on August 1 of the bank in Nogales, Arizona, the High Fives headed east and split up. The gang's leader, Black Jack Christian, and George Musgrave got away.

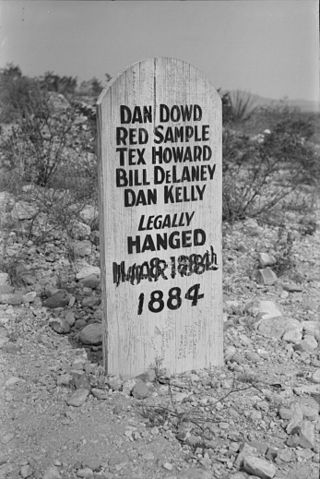

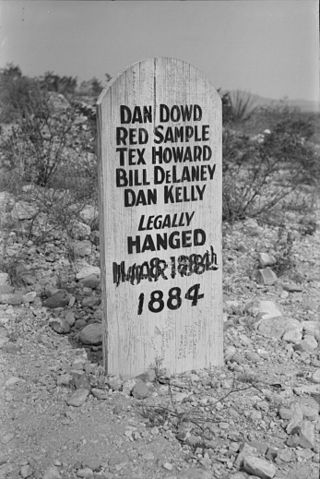

The Bisbee massacre occurred in Bisbee, Arizona, on December 8, 1883, when six outlaws who were part of the Cochise County Cowboys robbed a general store. Believing the general store's safe contained a mining payroll of $7,000, they timed the robbery incorrectly and were only able to steal between $800 and $3,000, along with a gold watch and jewelry. During the robbery, members of the gang killed five people, including a lawman and a pregnant woman. Six men were convicted of the robbery and murders. John Heath, who was accused of organizing the robbery, was tried separately and sentenced to life in prison. The other five men were convicted of murder and sentenced to hang.

The Fairbank train robbery occurred on the night of February 15, 1900, when some bandits attempted to hold up a Wells Fargo express car at the town of Fairbank, Arizona. Although it was thwarted by Jeff Milton, who managed to kill "Three Fingered Jack" Dunlop in an exchange of gunfire, the train robbery was unique for being one of the few to have occurred in a public place and was also one of the last during the Old West period.

Berry Washington was a 72-year-old black man who was lynched in Milan, Georgia, in 1919. He was in jail after killing a white man who was attacking two young girls. He was taken from jail and lynched by a mob.

This is a list with images of some of the historic structures and places in the Fort Huachuca National Historic District in Arizona. The district, also known as Old Fort Huachuca, is located within Fort Huachuca an active United States Army installation under the command of the United States Army Installation Management Command. The fort sits at the base of the Huachuca Mountains four miles west of the town of Sierra Vista, on AZ 90 in Cochise County, Arizona.

The Bisbee Historic District is a historic district located in Bisbee, Arizona, and has all the essential features of a prosperous, early twentieth century mining town. It has been listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1980. The district has 80 contributing buildings, with various architectural styles including Colonial Revival, Mission Revival/Spanish Revival, and Italianate architecture.