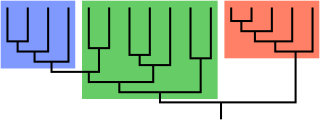

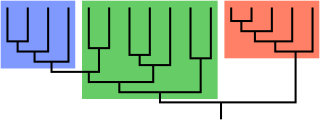

Cladistics is an approach to biological classification in which organisms are categorized in groups ("clades") based on hypotheses of most recent common ancestry. The evidence for hypothesized relationships is typically shared derived characteristics (synapomorphies) that are not present in more distant groups and ancestors. However, from an empirical perspective, common ancestors are inferences based on a cladistic hypothesis of relationships of taxa whose character states can be observed. Theoretically, a last common ancestor and all its descendants constitute a (minimal) clade. Importantly, all descendants stay in their overarching ancestral clade. For example, if the terms worms or fishes were used within a strict cladistic framework, these terms would include humans. Many of these terms are normally used paraphyletically, outside of cladistics, e.g. as a 'grade', which are fruitless to precisely delineate, especially when including extinct species. Radiation results in the generation of new subclades by bifurcation, but in practice sexual hybridization may blur very closely related groupings.

In biological phylogenetics, a clade, also known as a monophyletic group or natural group, is a grouping of organisms that are monophyletic – that is, composed of a common ancestor and all its lineal descendants – on a phylogenetic tree. In the taxonomical literature, sometimes the Latin form cladus is used rather than the English form. Clades are the fundamental unit of cladistics, a modern approach to taxonomy adopted by most biological fields.

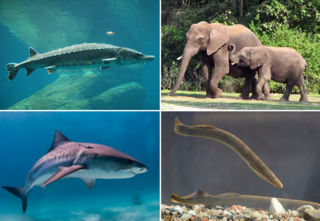

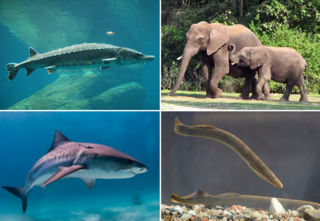

Vertebrates are deuterostomal animals with bony or cartilaginous axial endoskeleton — known as the vertebral column, spine or backbone — around and along the spinal cord, including all fish, amphibians, reptiles, birds and mammals. The vertebrates consist of all the taxa within the subphylum Vertebrata and represent the overwhelming majority of the phylum Chordata, with currently about 69,963 species described.

Lobopodians are members of the informal group Lobopodia, or the formally erected phylum Lobopoda Cavalier-Smith (1998). They are panarthropods with stubby legs called lobopods, a term which may also be used as a common name of this group as well. While the definition of lobopodians may differ between literatures, it usually refers to a group of soft-bodied, marine worm-like fossil panarthropods such as Aysheaia and Hallucigenia.

A tetrapod is any four-limbed vertebrate animal of the superclass Tetrapoda. Tetrapods include all extant and extinct amphibians and amniotes, with the latter in turn evolving into two major clades, the sauropsids and synapsids. Some tetrapods such as snakes, legless lizards, and caecilians had evolved to become limbless via mutations of the Hox gene, although some do still have a pair of vestigial spurs that are remnants of the hindlimbs.

Amniotes are tetrapod vertebrate animals belonging to the clade Amniota, a large group that comprises the vast majority of living terrestrial and semiaquatic vertebrates. Amniotes evolved from amphibian ancestors during the Carboniferous period and further diverged into two groups, namely the sauropsids and synapsids. They are distinguished from the other living tetrapod clade — the non-amniote lissamphibians — by the development of three extraembryonic membranes, thicker and keratinized skin, and costal respiration.

Vertebrate paleontology is the subfield of paleontology that seeks to discover, through the study of fossilized remains, the behavior, reproduction and appearance of extinct vertebrates. It also tries to connect, by using the evolutionary timeline, the animals of the past and their modern-day relatives.

Sauropsida is a clade of amniotes, broadly equivalent to the class Reptilia, though typically used in a broader sense to include both extinct stem-group relatives of modern reptiles, as well as birds. The most popular definition states that Sauropsida is the sibling taxon to Synapsida, the other clade of amniotes which includes mammals as its only modern representatives. Although early synapsids have historically been referred to as "mammal-like reptiles", all synapsids are more closely related to mammals than to any modern reptile. Sauropsids, on the other hand, include all amniotes more closely related to modern reptiles than to mammals. This includes Aves (birds), which are recognized as a subgroup of archosaurian reptiles despite originally being named as a separate class in Linnaean taxonomy.

Archosauria is a clade of diapsid sauropsid tetrapods, with birds and crocodilians being the only living representatives. Archosaurs are broadly classified as reptiles, in the cladistic sense of the term, which includes birds. Extinct archosaurs include non-avian dinosaurs, pterosaurs and extinct relatives of crocodilians. Modern paleontologists define Archosauria as a crown group that includes the most recent common ancestor of living birds and crocodilians, and all of its descendants. The base of Archosauria splits into two clades: Pseudosuchia, which includes crocodilians and their extinct relatives; and Avemetatarsalia, which includes birds and their extinct relatives.

The Batrachomorpha are a clade containing recent and extinct amphibians that are more closely related to modern amphibians than they are to mammals and reptiles. According to many analyses they include the extinct Temnospondyli; some show that they include the Lepospondyli instead. The name traditionally indicated a more limited group.

In phylogenetics, a sister group or sister taxon, also called an adelphotaxon, comprises the closest relative(s) of another given unit in an evolutionary tree.

Pseudosuchia is one of two major divisions of Archosauria, including living crocodilians and all archosaurs more closely related to crocodilians than to birds. Pseudosuchians are also informally known as "crocodilian-line archosaurs". Despite Pseudosuchia meaning "false crocodiles", the name is a misnomer as true crocodilians are now defined as a subset of the group.

Avemetatarsalia is a clade of diapsid reptiles containing all archosaurs more closely related to birds than to crocodilians. The two most successful groups of avemetatarsalians were the dinosaurs and pterosaurs. Dinosaurs were the largest terrestrial animals for much of the Mesozoic Era, and one group of small feathered dinosaurs has survived up to the present day. Pterosaurs were the first flying vertebrates and persisted through the Mesozoic before dying out at the Cretaceous-Paleogene (K-Pg) extinction event. Both dinosaurs and pterosaurs appeared in the Triassic Period, shortly after avemetatarsalians as a whole. The name Avemetatarsalia was first established by British palaeontologist Michael Benton in 1999. An alternate name is Pan-Aves, or "all birds", in reference to its definition containing all animals, living or extinct, which are more closely related to birds than to crocodilians.

Phylogenetic nomenclature is a method of nomenclature for taxa in biology that uses phylogenetic definitions for taxon names as explained below. This contrasts with the traditional method, by which taxon names are defined by a type, which can be a specimen or a taxon of lower rank, and a description in words. Phylogenetic nomenclature is regulated currently by the International Code of Phylogenetic Nomenclature (PhyloCode).

Phylogenetic bracketing is a method of inference used in biological sciences. It is used to infer the likelihood of unknown traits in organisms based on their position in a phylogenetic tree. One of the main applications of phylogenetic bracketing is on extinct organisms, known only from fossils, going all the way back to the last universal common ancestor (LUCA). The method is often used for understanding traits that do not fossilize well, such as soft tissue anatomy, physiology and behaviour. By considering the closest and second-closest well-known organisms, traits can be asserted with a fair degree of certainty, though the method is extremely sensitive to problems from convergent evolution.

Ornithurae is a natural group which includes the common ancestor of Ichthyornis, Hesperornis, and all modern birds as well as all other descendants of that common ancestor.

Alligatoroidea is one of three superfamilies of crocodylians, the other two being Crocodyloidea and Gavialoidea. Alligatoroidea evolved in the Late Cretaceous period, and consists of the alligators and caimans, as well as extinct members more closely related to the alligators than the two other groups.

Crocodyliformes is a clade of crurotarsan archosaurs, the group often traditionally referred to as "crocodilians". They are the first members of Crocodylomorpha to possess many of the features that define later relatives. They are the only pseudosuchians to survive the K-Pg extinction event.

A ghost lineage is a hypothesized ancestor in a species lineage that has left no fossil evidence, but can still be inferred to exist or have existed because of gaps in the fossil record or genomic evidence. The process of determining a ghost lineage relies on fossilized evidence before and after the hypothetical existence of the lineage and extrapolating relationships between organisms based on phylogenetic analysis. Ghost lineages assume unseen diversity in the fossil record and serve as predictions for what the fossil record could eventually yield; these hypotheses can be tested by unearthing new fossils or running phylogenetic analyses.

Reptiles arose about 320 million years ago during the Carboniferous period. Reptiles, in the traditional sense of the term, are defined as animals that have scales or scutes, lay land-based hard-shelled eggs, and possess ectothermic metabolisms. So defined, the group is paraphyletic, excluding endothermic animals like birds that are descended from early traditionally-defined reptiles. A definition in accordance with phylogenetic nomenclature, which rejects paraphyletic groups, includes birds while excluding mammals and their synapsid ancestors. So defined, Reptilia is identical to Sauropsida.