Human skin color ranges from the darkest brown to the lightest hues. Differences in skin color among individuals is caused by variation in pigmentation, which is the result of genetics, exposure to the sun, disorders, or all of these. Differences across populations evolved through natural selection or sexual selection, because of social norms and differences in environment, as well as regulations of the biochemical effects of ultraviolet radiation penetrating the skin.

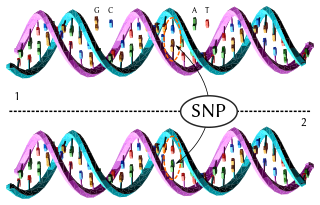

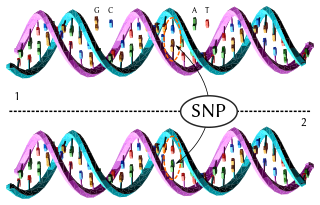

In genetics and bioinformatics, a single-nucleotide polymorphism is a germline substitution of a single nucleotide at a specific position in the genome that is present in a sufficiently large fraction of considered population.

Eye color is a polygenic phenotypic trait determined by two factors: the pigmentation of the eye's iris and the frequency-dependence of the scattering of light by the turbid medium in the stroma of the iris.

Genetic genealogy is the use of genealogical DNA tests, i.e., DNA profiling and DNA testing, in combination with traditional genealogical methods, to infer genetic relationships between individuals. This application of genetics came to be used by family historians in the 21st century, as DNA tests became affordable. The tests have been promoted by amateur groups, such as surname study groups or regional genealogical groups, as well as research projects such as the Genographic Project.

A genealogical DNA test is a DNA-based genetic test used in genetic genealogy that looks at specific locations of a person's genome in order to find or verify ancestral genealogical relationships, or to estimate the ethnic mixture of an individual. Since different testing companies use different ethnic reference groups and different matching algorithms, ethnicity estimates for an individual vary between tests, sometimes dramatically.

Cheddar Man is a human male fossil found in Gough's Cave in Cheddar Gorge, Somerset, England. The skeletal remains date to around the mid-to-late 9th millennium BC, corresponding to the Mesolithic period, and it appears that he died a violent death. A large crater-like lesion just above the skull's right orbit suggests that the man may have also been suffering from a bone infection.

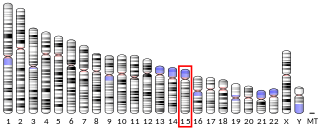

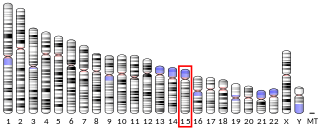

Sodium/potassium/calcium exchanger 5 (NCKX5), also known as solute carrier family 24 member 5 (SLC24A5), is a protein that in humans is encoded by the SLC24A5 gene that has a major influence on natural skin colour variation. The NCKX5 protein is a member of the potassium-dependent sodium/calcium exchanger family. Sequence variation in the SLC24A5 gene, particularly a non-synonymous SNP changing the amino acid at position 111 in NCKX5 from alanine to threonine, has been associated with differences in skin pigmentation.

In population genetics, an ancestry-informative marker (AIM) is a single-nucleotide polymorphism that exhibits substantially different frequencies between different populations. A set of many AIMs can be used to estimate the proportion of ancestry of an individual derived from each population.

DNAPrint Genomics was a genetics company with a wide range of products related to genetic profiling. They were the first company to introduce forensic and consumer genomics products, which were developed immediately upon the publication of the first complete draft of the human genome in the early 2000s. They researched, developed, and marketed the first ever consumer genomics product, based on "Ancestry Informative Markers" which they used to correctly identify the BioGeographical Ancestry (BGA) of a human based on a sample of their DNA. They also researched, developed and marketed the first ever forensic genomics product - DNAWITNESS - which was used to create a physical profile of donors of crime scene DNA. The company reached a peak of roughly $3M/year revenues but ceased operations in February 2009.

In Brazil, a sarará is a multiracial person, being a particular kind of mulato or juçara, with perceivable Black African facial features, light complexion and fair but curly hair, called cabelo crespo, or fair but Afro-like frizzly hair, called carapinha, cabelo encarapinhado or cabelo pixaim. In the 1998 IBGE PME, 0.04% of respondents identified, in an inquiry on race/colour, as "sarará".

mt-SNP is a single nucleotide polymorphism on the mitochondrial chromosome. mt-SNPs are often used in maternal genealogical DNA testing.

The Y Chromosome Haplotype Reference Database (YHRD) is an open-access, annotated collection of population samples typed for Y chromosomal sequence variants. Two important objectives are pursued: (1) the generation of reliable frequency estimates for Y-STR haplotypes and Y-SNP haplotypes to be used in the quantitative assessment of matches in forensic and kinship cases and (2) the characterization of male lineages to draw conclusions about the origins and history of human populations. The database is endorsed by the International Society for Forensic Genetics (ISFG). By May 2023 about 350,000 Y chromosomes typed for 9-29 STR loci have been directly submitted by worldwide forensic institutions and universities. In geographic terms, about 53% of the YHRD samples stem from Asia, 21% from Europe, 12% from North America, 10% from Latin America, 3% from Africa, 0.8% from Oceania/Australia and 0.2% from the Arctic. The 1.406 individual sampling projects are described in about 800 peer-reviewed publications

CeCe Moore is an American genetic genealogist who has been described as the country's foremost such entrepreneur. She has appeared as a guest on many TV shows and as a consultant on others such as Finding Your Roots. She has helped law enforcement agencies in identifying suspects in over 50 cold cases in one year using DNA and genetic genealogy. In May 2020, she began appearing in a prime time ABC television series called The Genetic Detective in which each episode recounts a cold case she helped solve.

Investigative genetic genealogy, also known as forensic genetic genealogy, is the emerging practice of utilizing genetic information from direct-to-consumer companies for identifying suspects or victims in criminal cases. As of December 2023, the use of this technology has solved a total of 651 criminal cases, including 318 individual perpetrators who were brought to light. There have also been 464 decedents identified, as well as 4 living does. The investigative power of genetic genealogy revolves around the use of publicly accessible genealogy databases such as GEDMatch and FamilyTreeDNA. On GEDMatch, users are able to upload their genetic data from any direct-to-consumer company in an effort to identify relatives that have tested at companies other than their own.

Parabon NanoLabs, Inc. is a company based in Reston, Virginia, that develops nanopharmaceuticals and provides DNA phenotyping services for law enforcement organizations.

Jay Roland Cook and Tanya Van Cuylenborg were a Canadian couple from Saanich, British Columbia who were murdered while on a trip to Seattle, Washington in November 1987.

In archaeogenetics, the term Western Hunter-Gatherer (WHG), West European Hunter-Gatherer, Western European Hunter-Gatherer, Villabruna cluster, or Oberkassel cluster is the name given to a distinct ancestral component of modern Europeans, representing descent from a population of Mesolithic hunter-gatherers who scattered over Western, Southern and Central Europe, from the British Isles in the west to the Carpathians in the east, following the retreat of the ice sheet of the Last Glacial Maximum.

The rape and murder of Angie Dodge occurred in Idaho Falls, Idaho on June 13, 1996. However, the true perpetrator was not apprehended until May 2019.

Peter Matthias Schneider was a German forensic geneticist. He was a full professor at the Institute of Legal Medicine of the University of Cologne.

SallyAnn Harbison is a New Zealand forensic scientist. She leads the forensic biology team at the Institute of Environmental Science and Research, and is an associate professor at the University of Auckland. Harbison was appointed a Member of the New Zealand Order of Merit in 2021 and in the same year was elected as a Fellow of the Royal Society Te Apārangi.