Related Research Articles

A banshee is a female spirit in Irish folklore who heralds the death of a family member, usually by screaming, wailing, shrieking, or keening. Her name is connected to the mythologically important tumuli or "mounds" that dot the Irish countryside, which are known as síde in Old Irish.

In Irish mythology, Donn is an ancestor of the Gaels and is believed to have been a god of the dead. Donn is said to dwell in Tech Duinn, where the souls of the dead gather. He may have originally been an aspect of the Dagda. Folklore about Donn survived into the modern era in parts of Ireland, in which he is said to be a phantom horseman riding a white horse.

Irish mythology is the body of myths native to the island of Ireland. It was originally passed down orally in the prehistoric era, being part of ancient Celtic religion. Many myths were later written down in the early medieval era by Christian scribes, who modified and Christianized them to some extent. This body of myths is the largest and best preserved of all the branches of Celtic mythology. The tales and themes continued to be developed over time, and the oral tradition continued in Irish folklore alongside the written tradition, but the main themes and characters remained largely consistent.

Lugh or Lug is a figure in Irish mythology. A member of the Tuatha Dé Danann, a group of supernatural beings, Lugh is portrayed as a warrior, a king, a master craftsman and a savior. He is associated with skill and mastery in multiple disciplines, including the arts. Lugh also has associations with oaths, truth and the law, and therefore with rightful kingship. Lugh is linked with the harvest festival of Lughnasadh, which bears his name. His most common epithets are Lámfada[ˈl̪ˠaːw ad̪ˠə] and Samildánach[ˈsˠawˠil d̪ˠaːnˠəxˠ].

Aos sí is the Irish name for a supernatural race in Celtic mythology – spelled sìth by the Scots, but pronounced the same – comparable to fairies or elves. They are said to descend from the Tuatha Dé Danann, meaning the "People of Danu", depending on the Abrahamic or pagan tradition.

The TuathaDé Danann, also known by the earlier name Tuath Dé, are a supernatural race in Irish mythology. Many of them are thought to represent deities of pre-Christian Gaelic Ireland.

The Dagda is an important god in Irish mythology. One of the Tuatha Dé Danann, the Dagda is portrayed as a father-figure, king, and druid. He is associated with fertility, agriculture, manliness and strength, as well as magic, druidry and wisdom. He can control life and death, the weather and crops, as well as time and the seasons.

In Irish mythology, Aengus or Óengus is one of the Tuatha Dé Danann and probably originally a god associated with youth, love, summer and poetic inspiration. The son of The Dagda and Boann, Aengus is also known as Macan Óc, and corresponds to the Welsh mythical figure Mabon and the Celtic god Maponos. He plays a central role in five Irish myths.

In Irish mythology, *Danu is an obscure figure of Irish mythology, whose sole attestation is in the genitive in the name of the Tuatha dé Danann. Though primarily seen as an ancestral figure, some Victorian sources also associate her with the land.

In Irish mythology, Bodb Derg or Bodhbh Dearg was a son of Eochaid Garb or the Dagda, and the Dagda's successor as King of the Tuatha Dé Danann.

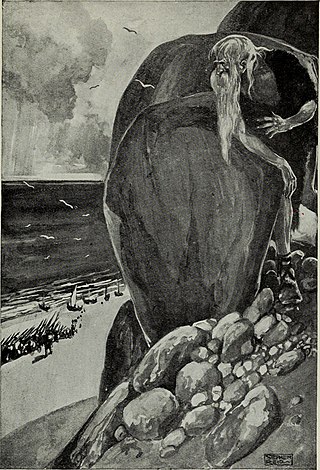

The Fomorians or Fomori are a supernatural race in Irish mythology, who are often portrayed as hostile and monstrous beings. Originally they were said to come from under the sea or the earth. Later, they were portrayed as sea raiders and giants. They are enemies of Ireland's first settlers and opponents of the Tuatha Dé Danann, the other supernatural race in Irish mythology; although some members of the two races have offspring. The Tuath Dé defeat the Fomorians in the Battle of Mag Tuired. This has been likened to other Indo-European myths of a war between gods, such as the Æsir and Vanir in Norse mythology and the Olympians and Titans in Greek mythology.

Nemed or Nimeth is a character in medieval Irish legend. According to the Lebor Gabála Érenn, he was the leader of the third group of people to settle in Ireland: the Muintir Nemid, Clann Nemid or "Nemedians". They arrived thirty years after the Muintir Partholóin, their predecessors, had died out. Nemed eventually dies of plague and his people are oppressed by the Fomorians. They rise up against the Fomorians, attacking their tower out at sea, but most are killed and the survivors leave Ireland. Their descendants become the Fir Bolg and the Tuatha Dé Danann.

A leprechaun is a diminutive supernatural being in Irish folklore, classed by some as a type of solitary fairy. They are usually depicted as little bearded men, wearing a coat and hat, who partake in mischief. In later times, they have been depicted as shoe-makers who have a hidden pot of gold at the end of the rainbow.

In Irish origin myths, Míl Espáine or Míl Espáne is the mythical ancestor of the final inhabitants of Ireland, the "sons of Míl" or Milesians, who represent the vast majority of the Irish Gaels. His father was Bile, son of Breogan. Modern historians believe he is a creation of medieval Irish Christian writers.

Irish folklore refers to the folktales, balladry, music, dance, and so forth, ultimately, all of folk culture.

A gancanagh is a male fairy from the mythology of Northern Ireland, known for seducing women.

In Celtic mythology, the Otherworld is the realm of the deities and possibly also the dead. In Gaelic and Brittonic myth it is usually a supernatural realm of everlasting youth, beauty, health, abundance and joy. It is described either as a parallel world that exists alongside our own, or as a heavenly land beyond the sea or under the earth. The Otherworld is usually elusive, but various mythical heroes visit it either through chance or after being invited by one of its residents. They often reach it by entering ancient burial mounds or caves, or by going under water or across the western sea. Sometimes, they suddenly find themselves in the Otherworld with the appearance of a magic mist, supernatural beings or unusual animals. An otherworldly woman may invite the hero into the Otherworld by offering an apple or a silver apple branch, or a ball of thread to follow as it unwinds.

Slievenamon or Slievenaman is a mountain with a height of 721 metres (2,365 ft) in County Tipperary, Ireland. It rises from a plain that includes the towns of Fethard, Clonmel and Carrick-on-Suir. The mountain is steeped in folklore and is associated with Fionn mac Cumhaill. On its summit are the remains of ancient burial cairns, which were seen as portals to the Otherworld. Much of its lower slopes are wooded, and formerly most of the mountain was covered in woodland. A low hill attached to Slievenamon, Carrigmaclear, was the site of a battle during the Irish Rebellion of 1798.

The leannán sídhe is a figure from Irish Folklore. She is depicted as a beautiful woman of the Aos Sí who takes a human lover. Lovers of the leannán sídhe are said to live brief, though highly inspired, lives. The name comes from the Gaelic words for a sweetheart, lover, or concubine and the term for inhabitants of fairy mounds (fairy). While the leannán sídhe is most often depicted as a female fairy, there is at least one reference to a male leannán sídhe troubling a mortal woman.

In folklore and literature, the Fairy Queen or Queen of the Fairies is a female ruler of the fairies, sometimes but not always paired with a king. Depending on the work, she may be named or unnamed; Titania and Mab are two frequently used names. Numerous characters, goddesses or folkloric spirits worldwide have been labeled as Fairy Queens.

References

- 1 2 Evans-Wentz, Walter Yeeling (1911). The Fairy-faith in Celtic Countries. H. Frowde. pp. 42–44. ISBN 9781530177868.

- 1 2 Mac Neill, Eoin (1919). Phases of Irish History. Gill and Son. p. 87.

- 1 2 3 Hyde, Douglas (1910). Beside the Fire: A Collection of Irish Gaelic Folk Stories. D. Nutt. pp. 86–87.

- ↑ Transactions of the Ossianic Society for the Year 1854, Volume 2. Dublin: Printed under the direction of the Council. 1855. p. 187.

- 1 2 Briggs, Katharine Mary (1976). An Encyclopedia of Fairies, Hobgoblins, Brownies, Boogies, and Other Supernatural Creatures. Pantheon Books. pp. 125–127.

- ↑ MacKillop, James (1998). Dictionary of Celtic Mythology. Oxford University Press. p. 201.

- ↑ Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland (1905). The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland. Vol. 35. The Society. p. 34.

- 1 2 3 4 5 O hOgáin, Dáithí (2006). The Lore of Ireland: An Encyclopaedia of Myth, Legend and Romance. Boydell Press. pp. 234–235.

- ↑ Éigse: A Journal of Irish Studies. Vol. 7. National University of Ireland. 1953. p. 91.

- ↑ Bergin, Osborn (1923). "Unpublished Irish Poems XXII. To a Harp". Studies. 12: 277.

- ↑ Transactions of the Ossianic Society for the Year 1854. Vol. II. Printed under the direction of the Council. 1855. pp. 187, 195.

- ↑ Squire, Charles (1905). The Mythology Of The British Islands. Blackie and Son Limited. pp. 136, 212, 243.

- ↑ Wilde, Francesca (1887). Ancient Legends, Mystic Charms, and Superstitions of Ireland, Volume 1. Ticknor and Company. p. 252.

- ↑ Evans-Wentz, Walter Yeeling (1911). The Fairy-faith in Celtic Countries. H. Frowde. p. 28. ISBN 9781530177868.

- ↑ Wilde, Francesca (1887). Ancient Legends, Mystic Charms, and Superstitions of Ireland, Volume 1. Ticknor and Company. pp. 77–82.

- ↑ Wilde, Francesca (1887). Ancient Legends, Mystic Charms, and Superstitions of Ireland, Volume 1. Ticknor and Company. pp. 145–148.

- ↑ Ó Súilleabháín, Seán (1942). A Handbook of Irish Folklore. Educational Company of Ireland. pp. 452–3, 495–6.

- ↑ "Fairy Mythology of Ireland". The Dublin University Magazine, A Literary and Political Journal. 63: 647. June 1864 – via HathiTrust.