A fairy is a type of mythical being or legendary creature, generally described as anthropomorphic, found in the folklore of multiple European cultures, a form of spirit, often with metaphysical, supernatural, or preternatural qualities.

Sir Thomas de Ercildoun, better remembered as Thomas the Rhymer, also known as Thomas Learmont or True Thomas, was a Scottish laird and reputed prophet from Earlston in the Borders. Thomas' gift of prophecy is linked to his poetic ability.

A leprechaun is a diminutive supernatural being in Irish folklore, classed by some as a type of solitary fairy. They are usually depicted as little bearded men, wearing a coat and hat, who partake in mischief. In later times, they have been depicted as shoe-makers who have a hidden pot of gold at the end of the rainbow.

A trow is a malignant or mischievous fairy or spirit in the folkloric traditions of the Orkney and Shetland islands. Trows may be regarded as monstrous giants at times, or quite the opposite, short-statured fairies dressed in grey.

A hobgoblin is a household spirit, appearing in English folklore, once considered helpful, but which since the spread of Christianity has often been considered mischievous. Shakespeare identifies the character of Puck in his A Midsummer Night's Dream as a hobgoblin.

Fairies, particularly those of Irish, English, Scottish and Welsh folklore, have been classified in a variety of ways. Classifications – which most often come from scholarly analysis, and may not always accurately reflect local traditions – typically focus on behavior or physical characteristics.

Hermitage Castle is a semi-ruined castle in the border region of Scotland. It stands in the remote valley of the Hermitage Water, part of Liddesdale in Roxburghshire. It is under the care of Historic Scotland. The castle has a reputation, both from its history and its appearance, as one of the most sinister and atmospheric castles in Scotland.

Habetrot is a figure in folklore of the Border counties of Northern England and Lowland Scotland, associated with spinning and the spinning wheel.

Liddesdale, the valley of the Liddel Water, in the County of Roxburgh, southern Scotland, extends in a south-westerly direction from the vicinity of Peel Fell to the River Esk, a distance of 21 miles (34 km). The Waverley route of the North British Railway runs down the dale, and the Catrail, or Picts' Dyke, crosses its head.

In Scottish and Northern English folklore, a shellycoat is a type of bogeyman that haunts rivers and streams.

William II de Soules, Lord of Liddesdale and Butler of Scotland, was a Scottish Border noble during the Wars of Scottish Independence. William was the elder son of Nicholas II de Soules, Lord of Liddesdale and Butler of Scotland, and a cousin of Alexander Comyn, Earl of Buchan. He was the nephew of John de Soules, Guardian of Scotland.

Glashtyn is a legendary creature from Manx folklore.

The black dog is a supernatural, spectral, or demonic hellhound originating from English folklore that has also been seen throughout Europe and the Americas. It is usually unnaturally large with glowing red or yellow eyes, is often connected with the Devil, and is sometimes an omen of death. It is sometimes associated with electrical storms, and also with crossroads, barrows, places of execution and ancient pathways.

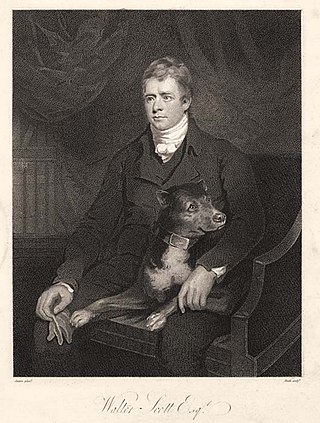

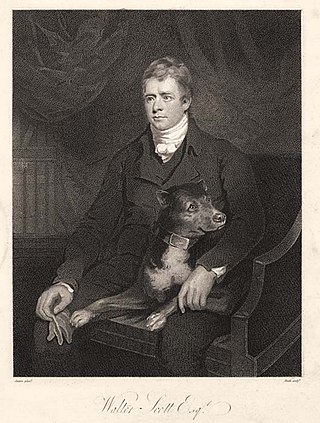

Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border is an anthology of Border ballads, together with some from north-east Scotland and a few modern literary ballads, edited by Walter Scott. It was first published by Archibald Constable in Edinburgh in 1802, but was expanded in several later editions, reaching its final state in 1830, two years before Scott's death. It includes many of the most famous Scottish ballads, such as Sir Patrick Spens, The Young Tamlane, The Twa Corbies, The Douglas Tragedy, Clerk Saunders, Kempion, The Wife of Usher's Well, The Cruel Sister, The Dæmon Lover, and Thomas the Rhymer. Scott enlisted the help of several collaborators, notably John Leyden, and found his ballads both by field research of his own and by consulting the manuscript collections of others. Controversially, in the editing of his texts he preferred literary quality over scholarly rigour, but Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border nevertheless attracted high praise from the first. It was influential both in Britain and on the Continent, and helped to decide the course of Scott's later career as a poet and novelist. In recent years it has been called "the most exciting collection of ballads ever to appear."

Seelie is a term for fairies in Scottish folklore, appearing in the form of seely wights or The Seelie Court. The Northern and Middle English word seely, and the Scots form seilie, mean "happy", "lucky" or "blessed." Despite their name, the seelie folk of legend could be morally ambivalent and dangerous. Calling them "seelie," similar to names such as "good neighbors," may have been a euphemism to ward off their anger.

Folk poetry is poetry that is part of a society's folklore, usually part of their oral tradition. When sung, folk poetry becomes a folk song.

The asrai is a type of aquatic fairy in English folklore and literature. They are usually depicted as female, live in lakes and are similar to the mermaid and nixie. Rather than originating from folklore, the asrai may have been invented by the Scottish poet Robert Williams Buchanan.

A brownie or broonie (Scots), also known as a brùnaidh or gruagach, is a household spirit or Hobgoblin from Scottish folklore that is said to come out at night while the owners of the house are asleep and perform various chores and farming tasks. The human owners of the house must leave a bowl of milk or cream or some other offering for the brownie, usually by the hearth. Brownies are described as easily offended and will leave their homes forever if they feel they have been insulted or in any way taken advantage of. Brownies are characteristically mischievous and are often said to punish or pull pranks on lazy servants. If angered, they are sometimes said to turn malicious, like boggarts.

Ninestane Rig is a small stone circle in Scotland near the English border. Located in Roxburghshire, near to Hermitage Castle, it was probably made between 2000 BC and 1250 BC, during the Late Neolithic or early Bronze Age. It is a scheduled monument and is part of a group with two other nearby ancient sites, these being Buck Stone standing stone and another standing stone at Greystone Hill. Settlements appear to have developed in the vicinity of these earlier ritual features in late prehistory and probably earlier.

In the folklore on the Anglo-Scottish border, the Brown Man of the Muirs is a dwarf who serves as a guardian spirit of wild animals. Also is a Folklore story, called "Brown Man of the Moor" in the Richardson's Table Book in the 19 century according to Publications of the Folklore Society of North England, where appear the creatures: boggleboes, bogies, redmen, portunes, grants, hobbits, hobgoblins and brown men.