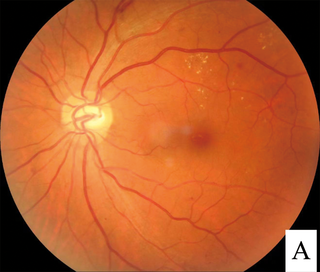

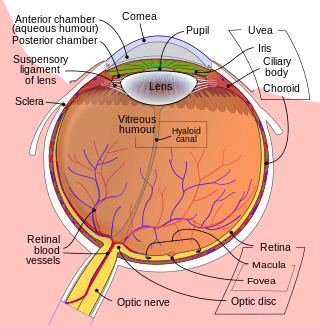

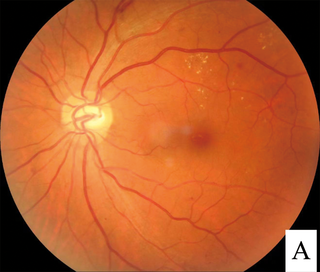

Diabetic retinopathy, is a medical condition in which damage occurs to the retina due to diabetes. It is a leading cause of blindness in developed countries.

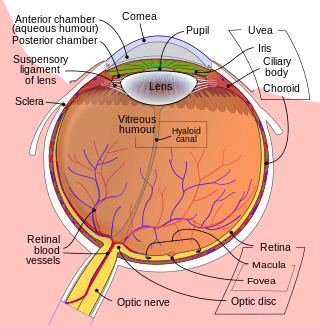

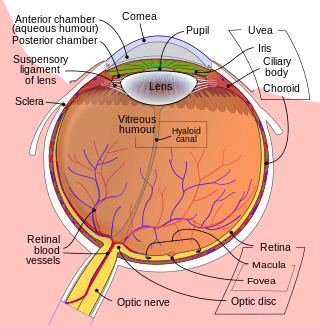

Vitrectomy is a surgery to remove some or all of the vitreous humor from the eye.

Retinoschisis is an eye disease characterized by the abnormal splitting of the retina's neurosensory layers, usually in the outer plexiform layer. Retinoschisis can be divided into degenerative forms which are very common and almost exclusively involve the peripheral retina and hereditary forms which are rare and involve the central retina and sometimes the peripheral retina. The degenerative forms are asymptomatic and involve the peripheral retina only and do not affect the visual acuity. Some rarer forms result in a loss of vision in the corresponding visual field.

The National Eye Institute (NEI) is part of the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH), an agency of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The mission of NEI is "to eliminate vision loss and improve quality of life through vision research." NEI consists of two major branches for research: an extramural branch that funds studies outside NIH and an intramural branch that funds research on the NIH campus in Bethesda, Maryland. Most of the NEI budget funds extramural research.

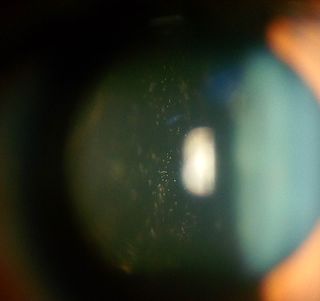

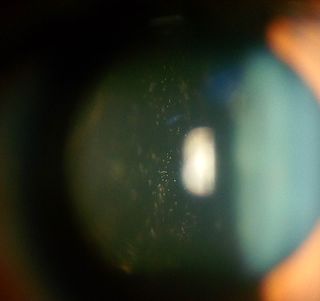

Eye surgery, also known as ophthalmic surgery or ocular surgery, is surgery performed on the eye or its adnexa. Eye surgery is part of ophthalmology and is performed by an ophthalmologist or eye surgeon. The eye is a fragile organ, and requires due care before, during, and after a surgical procedure to minimize or prevent further damage. An eye surgeon is responsible for selecting the appropriate surgical procedure for the patient, and for taking the necessary safety precautions. Mentions of eye surgery can be found in several ancient texts dating back as early as 1800 BC, with cataract treatment starting in the fifth century BC. It continues to be a widely practiced class of surgery, with various techniques having been developed for treating eye problems.

Phacoemulsification is a cataract surgery method in which the internal lens of the eye which has developed a cataract is emulsified with the tip of an ultrasonic handpiece and aspirated from the eye. Aspirated fluids are replaced with irrigation of balanced salt solution to maintain the volume of the anterior chamber during the procedure. This procedure minimises the incision size and reduces the recovery time and risk of surgery induced astigmatism.

Retinal detachment is a disorder of the eye in which the retina peels away from its underlying layer of support tissue. Initial detachment may be localized, but without rapid treatment the entire retina may detach, leading to vision loss and blindness. It is a surgical emergency.

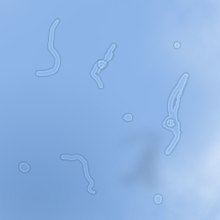

A posterior vitreous detachment (PVD) is a condition of the eye in which the vitreous membrane separates from the retina. It refers to the separation of the posterior hyaloid membrane from the retina anywhere posterior to the vitreous base.

A scleral buckle is one of several ophthalmologic procedures that can be used to repair a retinal detachment. Retinal detachments are usually caused by retinal tears, and a scleral buckle can be used to close the retinal break, both for acute and chronic retinal detachments.

Photopsia is the presence of perceived flashes of light in the field of vision.

Eales disease is a type of obliterative vasculopathy, also known as angiopathia retinae juvenilis, periphlebitis retinae or primary perivasculitis of the retina. It was first described by the British ophthalmologist Henry Eales (1852–1913) in 1880 and is a rare ocular disease characterized by inflammation and possible blockage of retinal blood vessels, abnormal growth of new blood vessels (neovascularization), and recurrent retinal and vitreal hemorrhages.

Intermediate uveitis is a form of uveitis localized to the vitreous and peripheral retina. Primary sites of inflammation include the vitreous of which other such entities as pars planitis, posterior cyclitis, and hyalitis are encompassed. Intermediate uveitis may either be an isolated eye disease or associated with the development of a systemic disease such as multiple sclerosis or sarcoidosis. As such, intermediate uveitis may be the first expression of a systemic condition. Infectious causes of intermediate uveitis include Epstein–Barr virus infection, Lyme disease, HTLV-1 virus infection, cat scratch disease, and hepatitis C.

Epiretinal membrane or macular pucker is a disease of the eye in response to changes in the vitreous humor or more rarely, diabetes. Sometimes, as a result of immune system response to protect the retina, cells converge in the macular area as the vitreous ages and pulls away in posterior vitreous detachment (PVD).

Optic pit, optic nerve pit, or optic disc pit (ODP) is rare a congenital excavation (or regional depression) of the optic disc (also optic nerve head), resulting from a malformation during development of the eye. The incidence of ODP is 1 in 10,000 people with no predilection for either gender. There is currently no known risk factors for their development. Optic pits are important because they are associated with posterior vitreous detachments (PVD) and even serous retinal detachments.

A macular hole is a small break in the macula, located in the center of the eye's light-sensitive tissue called the retina.

Intraocular hemorrhage is bleeding inside the eye. Bleeding can occur from any structure of the eye where there is vasculature or blood flow, including the anterior chamber, vitreous cavity, retina, choroid, suprachoroidal space, or optic disc.

Vitreous hemorrhage is the extravasation, or leakage, of blood into the areas in and around the vitreous humor of the eye. The vitreous humor is the clear gel that fills the space between the lens and the retina of the eye. A variety of conditions can result in blood leaking into the vitreous humor, which can cause impaired vision, floaters, and photopsia.

Vitreomacular adhesion (VMA) is a human medical condition where the vitreous gel of the human eye adheres to the retina in an abnormally strong manner. As the eye ages, it is common for the vitreous to separate from the retina. But if this separation is not complete, i.e. there is still an adhesion, this can create pulling forces on the retina that may result in subsequent loss or distortion of vision. The adhesion in of itself is not dangerous, but the resulting pathological vitreomacular traction (VMT) can cause severe ocular damage.

Robert Machemer was a German-American ophthalmologist, ophthalmic surgeon, and inventor. He is sometimes called the "father of modern retinal surgery."

Sickle cell retinopathy can be defined as retinal changes due to blood vessel damage in the eye of a person with a background of sickle cell disease. It can likely progress to loss of vision in late stages due to vitreous hemorrhage or retinal detachment. Sickle cell disease is a structural red blood cell disorder leading to consequences in multiple systems. It is characterized by chronic red blood cell destruction, vascular injury, and tissue ischemia causing damage to the brain, eyes, heart, lungs, kidneys, spleen, and musculoskeletal system.