Sociobiology is a field of biology that aims to explain social behavior in terms of evolution. It draws from disciplines including psychology, ethology, anthropology, evolution, zoology, archaeology, and population genetics. Within the study of human societies, sociobiology is closely allied to evolutionary anthropology, human behavioral ecology, evolutionary psychology, and sociology.

Theories of political behavior, as an aspect of political science, attempt to quantify and explain the influences that define a person's political views, ideology, and levels of political participation. Political behavior is the subset of human behavior that involves politics and power. Theorists who have had an influence on this field include Karl Deutsch and Theodor Adorno.

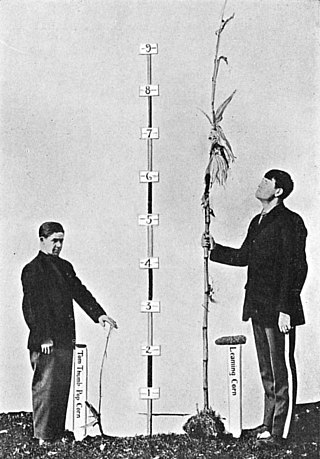

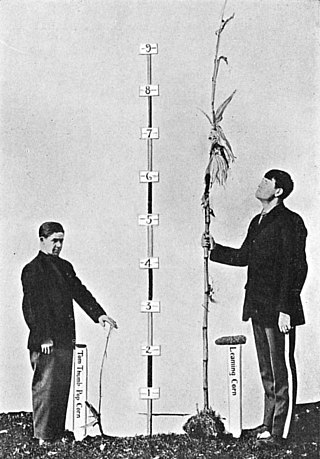

Nature versus nurture is a long-standing debate in biology and society about the relative influence on human beings of their genetic inheritance (nature) and the environmental conditions of their development (nurture). The alliterative expression "nature and nurture" in English has been in use since at least the Elizabethan period and goes back to medieval French. The complementary combination of the two concepts is an ancient concept. Nature is what people think of as pre-wiring and is influenced by genetic inheritance and other biological factors. Nurture is generally taken as the influence of external factors after conception e.g. the product of exposure, experience and learning on an individual.

Biological determinism, also known as genetic determinism, is the belief that human behaviour is directly controlled by an individual's genes or some component of their physiology, generally at the expense of the role of the environment, whether in embryonic development or in learning. Genetic reductionism is a similar concept, but it is distinct from genetic determinism in that the former refers to the level of understanding, while the latter refers to the supposedly causal role of genes. Biological determinism has been associated with movements in science and society including eugenics, scientific racism, and the debates around the heritability of IQ, the basis of sexual orientation, and sociobiology.

An ideology is a set of beliefs or philosophies attributed to a person or group of persons, especially those held for reasons that are not purely epistemic, in which "practical elements are as prominent as theoretical ones". Formerly applied primarily to economic, political, or religious theories and policies, in a tradition going back to Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, more recent use treats the term as mainly condemnatory.

Heritability is a statistic used in the fields of breeding and genetics that estimates the degree of variation in a phenotypic trait in a population that is due to genetic variation between individuals in that population. The concept of heritability can be expressed in the form of the following question: "What is the proportion of the variation in a given trait within a population that is not explained by the environment or random chance?"

Twin studies are studies conducted on identical or fraternal twins. They aim to reveal the importance of environmental and genetic influences for traits, phenotypes, and disorders. Twin research is considered a key tool in behavioral genetics and in related fields, from biology to psychology. Twin studies are part of the broader methodology used in behavior genetics, which uses all data that are genetically informative – siblings studies, adoption studies, pedigree, etc. These studies have been used to track traits ranging from personal behavior to the presentation of severe mental illnesses such as schizophrenia.

The heritability of autism is the proportion of differences in expression of autism that can be explained by genetic variation; if the heritability of a condition is high, then the condition is considered to be primarily genetic. Autism has a strong genetic basis. Although the genetics of autism are complex, autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is explained more by multigene effects than by rare mutations with large effects.

Research on the heritability of IQ inquires into the degree of variation in IQ within a population that is due to genetic variation between individuals in that population. There has been significant controversy in the academic community about the heritability of IQ since research on the issue began in the late nineteenth century. Intelligence in the normal range is a polygenic trait, meaning that it is influenced by more than one gene, and in the case of intelligence at least 500 genes. Further, explaining the similarity in IQ of closely related persons requires careful study because environmental factors may be correlated with genetic factors.

The field of psychology has been greatly influenced by the study of genetics. Decades of research have demonstrated that both genetic and environmental factors play a role in a variety of behaviors in humans and animals. The genetic basis of aggression, however, remains poorly understood. Aggression is a multi-dimensional concept, but it can be generally defined as behavior that inflicts pain or harm on another.

James H. Fowler is an American social scientist specializing in social networks, cooperation, political participation, and genopolitics. He is currently Professor of Medical Genetics in the School of Medicine and Professor of Political Science in the Division of Social Science at the University of California, San Diego. He was named a 2010 Fellow of the John Simon Guggenheim Foundation.

Gene–environment correlation is said to occur when exposure to environmental conditions depends on an individual's genotype.

Behavioural genetics, also referred to as behaviour genetics, is a field of scientific research that uses genetic methods to investigate the nature and origins of individual differences in behaviour. While the name "behavioural genetics" connotes a focus on genetic influences, the field broadly investigates the extent to which genetic and environmental factors influence individual differences, and the development of research designs that can remove the confounding of genes and environment. Behavioural genetics was founded as a scientific discipline by Francis Galton in the late 19th century, only to be discredited through association with eugenics movements before and during World War II. In the latter half of the 20th century, the field saw renewed prominence with research on inheritance of behaviour and mental illness in humans, as well as research on genetically informative model organisms through selective breeding and crosses. In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, technological advances in molecular genetics made it possible to measure and modify the genome directly. This led to major advances in model organism research and in human studies, leading to new scientific discoveries.

A number of studies have found that human biology can be linked with political orientation. This means that an individual's biology may predispose them to a particular political orientation and ideology. Many of the studies linking biology to politics remain controversial and nonreplicated.

The missing heritability problem refers to the difference between heritability estimates from genetic data and heritability estimates from twin and family data across many physical and mental traits, including diseases, behaviors, and other phenotypes. This is a problem that has significant implications for medicine, since a person's susceptibility to disease may depend more on the combined effect of all the genes in the background than on the disease genes in the foreground, or the role of genes may have been severely overestimated.

Neuropolitics is a science which investigates the interplay between the brain and politics. It combines work from a variety of scientific fields which includes neuroscience, political science, psychology, behavioral genetics, primatology, and ethology. Often, neuropolitics research borrow methods from cognitive neuroscience to investigate classic questions from political science such as how people make political decisions, form political / ideological attitudes, evaluate political candidates, and interact in political coalitions. However, another line of research considers the role that evolving political competition has had on the development of the brain in humans and other species. The research in neuropolitics often intersects with work in genopolitics, political psychology, political physiology, sociobiology, neuroeconomics, and neurolaw.

The interdisciplinary study of biology and political science is the application of theories and methods from the field of biology toward the scientific understanding of political behavior. The field is sometimes called biopolitics, a term that will be used in this article as a synonym although it has other, less related meanings. More generally, the field has also been called "politics and the life sciences".

Addiction vulnerability is an individual's risk of developing an addiction during their lifetime. There are a range of genetic and environmental risk factors for developing an addiction that vary across the population. Genetic and environmental risk factors each account for roughly half of an individual's risk for developing an addiction; the contribution from epigenetic risk factors to the total risk is unknown. Even in individuals with a relatively low genetic risk, exposure to sufficiently high doses of an addictive drug for a long period of time can result in an addiction. In other words, anyone can become an individual with a substance use disorder under particular circumstances. Research is working toward establishing a comprehensive picture of the neurobiology of addiction vulnerability, including all factors at work in propensity for addiction.

Peter K. Hatemi is an American political scientist and Distinguished Professor of Political Science, co-fund in Microbiology and Biochemistry at Pennsylvania State University. He is known for his research on the relationship between genetic factors and political attitudes and ideologies, the influence of narcissism on political attitudes as well as the underpinnings of violent behavior. He has also studied the relationship that other factors have to political orientations, finding that an individual's personality traits or moral foundations have no causal role in one's political orientations, but rather, that if there is a causal path, it is from political orientations to one's morals and personality traits.

Personality traits are patterns of thoughts, feelings and behaviors that reflect the tendency to respond in certain ways under certain circumstances.