Owner-occupancy or home-ownership is a form of housing tenure in which a person, called the owner-occupier, owner-occupant, or home owner, owns the home in which they live. The home can be a house, such as a single-family house, an apartment, condominium, or a housing cooperative. In addition to providing housing, owner-occupancy also functions as a real estate investment.

Imputed rent is the rental price an individual would pay for an asset they own. The concept applies to any capital good, but it is most commonly used in housing markets to measure the rent homeowners would pay for a housing unit equivalent to the one they own. Imputing housing rent is necessary to measure economic activity in national accounts. Because asset owners do not pay rent, owners' imputed rent must be measured indirectly.

A landlord is the owner of a house, apartment, condominium, land, or real estate which is rented or leased to an individual or business, who is called a tenant. When a juristic person is in this position, the term landlord is used. Other terms include lessor, housing provider, and owner. The term landlady may be used for the female owners. The manager of a pub in the United Kingdom, strictly speaking a licensed victualler, is referred to as the landlord/landlady. In political economy it refers to the owner of natural resources alone from which an economic rent, a form of passive income, is the income received.

Real estate economics is the application of economic techniques to real estate markets. It tries to describe, explain, and predict patterns of prices, supply, and demand. The closely related field of housing economics is narrower in scope, concentrating on residential real estate markets, while the research on real estate trends focuses on the business and structural changes affecting the industry. Both draw on partial equilibrium analysis, urban economics, spatial economics, basic and extensive research, surveys, and finance.

The affordability of housing in the UK reflects the ability to rent or buy property. There are various ways to determine or estimate housing affordability. One commonly used metric is the median housing affordability ratio; this compares the median price paid for residential property to the median gross annual earnings for full-time workers. According to official government statistics, housing affordability worsened between 2020 and 2021, and since 1997 housing affordability has worsened overall, especially in London. The most affordable local authorities in 2021 were in the North West, Wales, Yorkshire and The Humber, West Midlands and North East.

A real-estate bubble or property bubble is a type of economic bubble that occurs periodically in local or global real estate markets, and it typically follows a land boom. A land boom is a rapid increase in the market price of real property such as housing until they reach unsustainable levels and then declines. This period, during the run-up to the crash, is also known as froth. The questions of whether real estate bubbles can be identified and prevented, and whether they have broader macroeconomic significance, are answered differently by schools of economic thought, as detailed below.

The private rented sector (PRS) is a classification of United Kingdom housing tenure as described by the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government, a UK government department that monitors the national housing supply.

Affordable housing is housing which is deemed affordable to those with a household income at or below the median as rated by the national government or a local government by a recognized housing affordability index. Most of the literature on affordable housing refers to mortgages and a number of forms that exist along a continuum – from emergency homeless shelters, to transitional housing, to non-market rental, to formal and informal rental, indigenous housing, and ending with affordable home ownership.

The homeownership rate in the United States is the percentage of homes that are owned by their occupants. In 2009, it remained similar to that in some other post-industrial nations with 67.4% of all occupied housing units being occupied by the unit's owner. Homeownership rates vary depending on demographic characteristics of households such as ethnicity, race, type of household as well as location and type of settlement. In 2018, homeownership dropped to a lower rate than it was in 1994, with a rate of 64.2%.

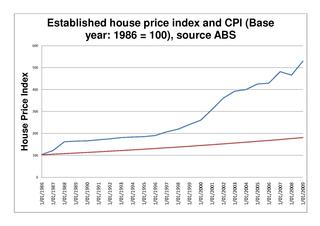

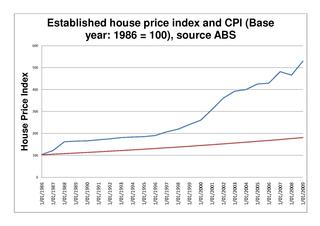

The Australian property market comprises the trade of land and its permanent fixtures located within Australia. The average Australian property price grew 0.5% per year from 1890 to 1990 after inflation, however rose from 1990 to 2017 at a faster rate. House prices in Australia receive considerable attention from the media and the Reserve Bank and some commentators have argued that there is an Australian property bubble.

The Australian property bubble is the economic theory that the Australian property market has become or is becoming significantly overpriced and due for a significant downturn. Since the early 2010s, various commentators, including one Treasury official, have claimed the Australian property market is in a significant bubble.

Housing in the state of Victoria, Australia is characterised by high rates of private housing ownership, minimal and lack of public housing and high demand for, and largely unaffordable, rental housing. Outside of Melbourne, home to 70% of the state's population, housing and rent is more affordable. In Melbourne, access to public housing is generally better, but housing and rent are less affordable.

Affordable housing in Canada is living spaces that are deemed financially accessible to those with a median household income in Canada. The property ladder continuum of affordable housing in Canada includes market, non-market, and government-subsidized housing.

Housing in the United Kingdom represents the largest non-financial asset class in the UK; its overall net value passed the £5 trillion mark in 2014. Housing includes modern and traditional styles. About 30% of homes are owned outright by their occupants, and a further 40% are owner-occupied on a mortgage. About 18% are social housing of some kind, and the remaining 12% are privately rented.

The property bubble in New Zealand is a major national economic and social issue. Since the early 1990s, house prices in New Zealand have risen considerably faster than incomes, putting increasing pressure on public housing providers as fewer households have access to housing on the private market. The property bubble has produced significant impacts on inequality in New Zealand, which now has one of the highest homelessness rate in the OECD and a record-high waiting list for public housing. Government policies have attempted to address the crisis since 2013, but have produced limited impacts to reduce prices or increase the supply of affordable housing. However, prices started falling in 2022 in response to tightening of mortgage availability and supply increasing. Some areas saw drops as high as around 9% - albeit from very high prices.

Affordable housing is housing that is deemed affordable to those with a median household income as rated by the national government or a local government by a recognized housing affordability index. A general rule is no more than 30% of gross monthly income should be spent on housing, to be considered affordable as the challenges of promoting affordable housing varies by location.

The Canadian property bubble refers to a significant rise in Canadian real estate prices from 2002 to present which some observers have called a real estate bubble. The Dallas Federal reserve rated Canadian real estate as "exuberant" beginning in 2003. From 2003 to 2018, Canada saw an increase in home and property prices of up to 337% in some cities. In 2016, the OECD warned that Canada's financial stability was at risk due to elevated housing prices, investment and household debt. By 2018, home-owning costs were above 1990 levels when Canada saw its last housing bubble burst. Bloomberg Economics ranked Canada as the second largest housing bubble across the OECD in 2019 and 2021. Toronto scored the highest in the world in Swiss bank UBS' real estate bubble index in 2022, with Vancouver also scoring among the 10 riskiest cities in the world. By 2023 Canada’s nonfinancial debt exceeded 300% of GDP and household debt surpassed 100% of GDP, both higher than the levels seen in the United States before the 2008 global financial crisis.

Negative gearing in Australia deals with the laws in the Australian income tax system relating to net loss suffered by a taxpayer on their investment property, commonly called negative gearing. Negative gearing can arise in a number of contexts; for example, with real estate investments, it arises when the net rental income is less than the mortgage loan interest payable, and with shares, when net dividend income is less than the interest payable on a margin loan.

Judith Nancy Yates was an Australian housing economist. She was a lecturer and associate professor at the University of Sydney from 1971 to 2009. As a social liberal economist, she published over 120 papers in academic journals and government and industry reports on most aspects of Australia's housing sector, most notably on distributional aspects of the tax and finance system, on affordability and the supply of low-rent housing.Throughout her career she was appointed to a number of government advisory committees, and she contributed to many government inquiries.

The Australian residential property market is the section of the Australian property market that provides rental properties by landlords to tenants. In Australia 31% of households rent their residences. The vast majority rent from private landlords, and a small minority rent from public housing authorities. Over the last three decades the proportion of Australians in public housing has halved, whilst the amount renting privately has grown. The average weekly price for a rental in Australia is $570 AUD. Sydney has the most expensive capital city rents. Rental rates have increased faster than inflation in recent years.