A respiratory therapist is a specialized healthcare practitioner trained in critical care and cardio-pulmonary medicine in order to work therapeutically with people who have acute critical conditions, cardiac and pulmonary disease. Respiratory therapists graduate from a college or university with a degree in respiratory therapy and have passed a national board certifying examination. The NBRC is responsible for credentialing as a CRT, or RRT,

A ventilator is a type of breathing apparatus, a class of medical technology that provides mechanical ventilation by moving breathable air into and out of the lungs, to deliver breaths to a patient who is physically unable to breathe, or breathing insufficiently. Ventilators may be computerized microprocessor-controlled machines, but patients can also be ventilated with a simple, hand-operated bag valve mask. Ventilators are chiefly used in intensive-care medicine, home care, and emergency medicine and in anesthesiology.

Mechanical ventilation or assisted ventilation is the medical term for using a machine called a ventilator to fully or partially provide artificial ventilation. Mechanical ventilation helps move air into and out of the lungs, with the main goal of helping the delivery of oxygen and removal of carbon dioxide. Mechanical ventilation is used for many reasons, including to protect the airway due to mechanical or neurologic cause, to ensure adequate oxygenation, or to remove excess carbon dioxide from the lungs. Various healthcare providers are involved with the use of mechanical ventilation and people who require ventilators are typically monitored in an intensive care unit.

Anesthesiology, anaesthesiology, or anaesthesia is the medical specialty concerned with the total perioperative care of patients before, during and after surgery. It encompasses anesthesia, intensive care medicine, critical emergency medicine, and pain medicine. A physician specialized in anesthesiology is called an anesthesiologist, anaesthesiologist, or anaesthetist, depending on the country. In some countries, the terms are synonymous, while in other countries, they refer to different positions and anesthetist is only used for non-physicians, such as nurse anesthetists.

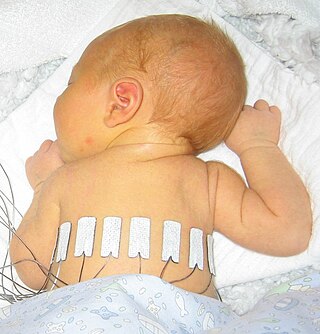

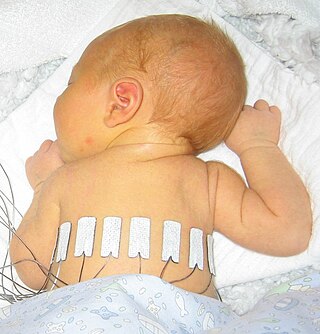

A neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), also known as an intensive care nursery (ICN), is an intensive care unit (ICU) specializing in the care of ill or premature newborn infants. The NICU is divided into several areas, including a critical care area for babies who require close monitoring and intervention, an intermediate care area for infants who are stable but still require specialized care, and a step down unit where babies who are ready to leave the hospital can receive additional care before being discharged.

A bag valve mask (BVM), sometimes known by the proprietary name Ambu bag or generically as a manual resuscitator or "self-inflating bag", is a hand-held device commonly used to provide positive pressure ventilation to patients who are not breathing or not breathing adequately. The device is a required part of resuscitation kits for trained professionals in out-of-hospital settings (such as ambulance crews) and is also frequently used in hospitals as part of standard equipment found on a crash cart, in emergency rooms or other critical care settings. Underscoring the frequency and prominence of BVM use in the United States, the American Heart Association (AHA) Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiac Care recommend that "all healthcare providers should be familiar with the use of the bag-mask device." Manual resuscitators are also used within the hospital for temporary ventilation of patients dependent on mechanical ventilators when the mechanical ventilator needs to be examined for possible malfunction or when ventilator-dependent patients are transported within the hospital. Two principal types of manual resuscitators exist; one version is self-filling with air, although additional oxygen (O2) can be added but is not necessary for the device to function. The other principal type of manual resuscitator (flow-inflation) is heavily used in non-emergency applications in the operating room to ventilate patients during anesthesia induction and recovery.

Ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) is a type of lung infection that occurs in people who are on mechanical ventilation breathing machines in hospitals. As such, VAP typically affects critically ill persons that are in an intensive care unit (ICU) and have been on a mechanical ventilator for at least 48 hours. VAP is a major source of increased illness and death. Persons with VAP have increased lengths of ICU hospitalization and have up to a 20–30% death rate. The diagnosis of VAP varies among hospitals and providers but usually requires a new infiltrate on chest x-ray plus two or more other factors. These factors include temperatures of >38 °C or <36 °C, a white blood cell count of >12 × 109/ml, purulent secretions from the airways in the lung, and/or reduction in gas exchange.

An intensivist, also known as a critical care doctor, is a medical practitioner who specializes in the care of critically ill patients, most often in the intensive care unit (ICU). Intensivists can be internists or internal medicine sub-specialists, anaesthesiologists, emergency medicine physicians, paediatricians, or surgeons who have completed a fellowship in critical care medicine. The intensivist must be competent not only in a broad spectrum of conditions among critically ill patients but also with the technical procedures and equipment used in the intensive care setting such as airway management, rapid sequence induction of anaesthesia, maintenance and weaning of sedation, central venous and arterial catheterisation, renal replacement therapy and management of mechanical ventilators.

An intensive care unit (ICU), also known as an intensive therapy unit or intensive treatment unit (ITU) or critical care unit (CCU), is a special department of a hospital or health care facility that provides intensive care medicine.

Critical care nursing is the field of nursing with a focus on the utmost care of the critically ill or unstable patients following extensive injury, surgery or life-threatening diseases. Critical care nurses can be found working in a wide variety of environments and specialties, such as general intensive care units, medical intensive care units, surgical intensive care units, trauma intensive care units, coronary care units, cardiothoracic intensive care units, burns unit, paediatrics and some trauma center emergency departments. These specialists generally take care of critically ill patients who require mechanical ventilation by way of endotracheal intubation and/or titratable vasoactive intravenous medications.

The Critical Care Air Transport Team (CCATT) concept dates from 1988, when Col. P.K. Carlton and Maj. J. Chris Farmer originated the development of this program while stationed at U.S. Air Force Hospital Scott, Scott Air Force Base, Illinois. Dr. Carlton was the Hospital Commander, and Dr. Farmer was a staff intensivist. The program was developed because of an inability to transport and care for a patient who became critically ill during a trans-Atlantic air evac mission in a C-141. They envisioned a highly portable intensive care unit (ICU) with sophisticated capabilities, carried in backpacks, that would match on-the-ground ICU functionality.

Neurocritical care is a medical field that treats life-threatening diseases of the nervous system and identifies, prevents, and treats secondary brain injury.

Geriatric intensive care unit is a special intensive care unit dedicated to management of critically ill elderly.

A pediatric intensive care unit, usually abbreviated to PICU, is an area within a hospital specializing in the care of critically ill infants, children, teenagers, and young adults aged 0–21. A PICU is typically directed by one or more pediatric intensivists or PICU consultants and staffed by doctors, nurses, and respiratory therapists who are specially trained and experienced in pediatric intensive care. The unit may also have nurse practitioners, physician assistants, physiotherapists, social workers, child life specialists, and clerks on staff, although this varies widely depending on geographic location. The ratio of professionals to patients is generally higher than in other areas of the hospital, reflecting the acuity of PICU patients and the risk of life-threatening complications. Complex technology and equipment is often in use, particularly mechanical ventilators and patient monitoring systems. Consequently, PICUs have a larger operating budget than many other departments within the hospital.

Bjørn Aage Ibsen was a Danish anesthetist and founder of intensive-care medicine.

Modes of mechanical ventilation are one of the most important aspects of the usage of mechanical ventilation. The mode refers to the method of inspiratory support. In general, mode selection is based on clinician familiarity and institutional preferences, since there is a paucity of evidence indicating that the mode affects clinical outcome. The most frequently used forms of volume-limited mechanical ventilation are intermittent mandatory ventilation (IMV) and continuous mandatory ventilation (CMV). There have been substantial changes in the nomenclature of mechanical ventilation over the years, but more recently it has become standardized by many respirology and pulmonology groups. Writing a mode is most proper in all capital letters with a dash between the control variable and the strategy.

Prone ventilation, sometimes called prone positioning or proning, is a method of mechanical ventilation with the patient lying face-down (prone). It improves oxygenation in most patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and reduces mortality. The earliest trial investigating the benefits of prone ventilation occurred in 1976. Since that time, many meta-analyses and one randomized control trial, the PROSEVA trial, have shown an increase in patients' survival with the more severe versions of ARDS. There are many proposed mechanisms, but they are not fully delineated. The proposed utility of prone ventilation is that this position will improve lung mechanics, improve oxygenation, and increase survival. Although improved oxygenation has been shown in multiple studies, this position change's survival benefit is not as clear. Similar to the slow adoption of low tidal volume ventilation utilized in ARDS, many believe that the investigation into the benefits of prone ventilation will likely be ongoing in the future.

The Society of Intensive Care Medicine (SICM) is the representative body for Intensive Care Medicine (ICM) professionals in Singapore.

Proning or prone positioning is the placement of patients into a prone position so that they are lying on their front. This is used in the treatment of patients in intensive care with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). It has been especially tried and studied for patients on ventilators but, during the COVID-19 pandemic, it is being used for patients with oxygen masks and CPAP as an alternative to ventilation.