In medicine, a pulse represents the tactile arterial palpation of the cardiac cycle (heartbeat) by trained fingertips. The pulse may be palpated in any place that allows an artery to be compressed near the surface of the body, such as at the neck, wrist, at the groin, behind the knee, near the ankle joint, and on foot. Pulse is equivalent to measuring the heart rate. The heart rate can also be measured by listening to the heart beat by auscultation, traditionally using a stethoscope and counting it for a minute. The radial pulse is commonly measured using three fingers. This has a reason: the finger closest to the heart is used to occlude the pulse pressure, the middle finger is used get a crude estimate of the blood pressure, and the finger most distal to the heart is used to nullify the effect of the ulnar pulse as the two arteries are connected via the palmar arches. The study of the pulse is known as sphygmology.

Blood pressure (BP) is the pressure of circulating blood against the walls of blood vessels. Most of this pressure results from the heart pumping blood through the circulatory system. When used without qualification, the term "blood pressure" refers to the pressure in a brachial artery, where it is most commonly measured. Blood pressure is usually expressed in terms of the systolic pressure over diastolic pressure in the cardiac cycle. It is measured in millimeters of mercury (mmHg) above the surrounding atmospheric pressure, or in kilopascals (kPa). The difference between the systolic and diastolic pressures is known as pulse pressure, while the average pressure during a cardiac cycle is known as mean arterial pressure.

Shock is the state of insufficient blood flow to the tissues of the body as a result of problems with the circulatory system. Initial symptoms of shock may include weakness, fast heart rate, fast breathing, sweating, anxiety, and increased thirst. This may be followed by confusion, unconsciousness, or cardiac arrest, as complications worsen.

In cardiac physiology, cardiac output (CO), also known as heart output and often denoted by the symbols , , or , is the volumetric flow rate of the heart's pumping output: that is, the volume of blood being pumped by a single ventricle of the heart, per unit time. Cardiac output (CO) is the product of the heart rate (HR), i.e. the number of heartbeats per minute (bpm), and the stroke volume (SV), which is the volume of blood pumped from the left ventricle per beat; thus giving the formula:

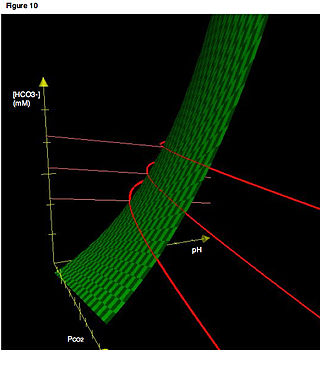

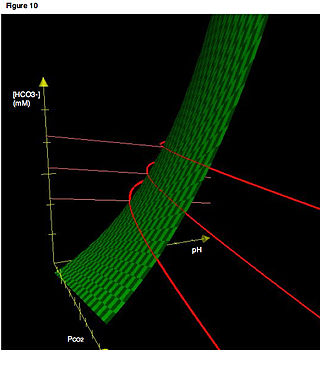

An arterial blood gas (ABG) test, or arterial blood gas analysis (ABGA) measures the amounts of arterial gases, such as oxygen and carbon dioxide. An ABG test requires that a small volume of blood be drawn from the radial artery with a syringe and a thin needle, but sometimes the femoral artery in the groin or another site is used. The blood can also be drawn from an arterial catheter.

Heart rate is the frequency of the heartbeat measured by the number of contractions of the heart per minute. The heart rate varies according to the body's physical needs, including the need to absorb oxygen and excrete carbon dioxide. It is also modulated by numerous factors, including genetics, physical fitness, stress or psychological status, diet, drugs, hormonal status, environment, and disease/illness, as well as the interaction between these factors. It is usually equal or close to the pulse measured at any peripheral point.

A sphygmomanometer, also known as a blood pressure monitor, or blood pressure gauge, is a device used to measure blood pressure, composed of an inflatable cuff to collapse and then release the artery under the cuff in a controlled manner, and a mercury or aneroid manometer to measure the pressure. Manual sphygmomanometers are used with a stethoscope when using the auscultatory technique.

Pulse oximetry is a noninvasive method for monitoring a person's blood oxygen saturation. Peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO2) readings are typically within 2% accuracy of the more accurate reading of arterial oxygen saturation (SaO2) from arterial blood gas analysis. But the two are correlated well enough that the safe, convenient, noninvasive, inexpensive pulse oximetry method is valuable for measuring oxygen saturation in clinical use.

Hypovolemic shock is a form of shock caused by severe hypovolemia. It could be the result of severe dehydration through a variety of mechanisms or blood loss. Hypovolemic shock is a medical emergency; if left untreated, the insufficient blood flow can cause damage to organs, leading to multiple organ failure.

At the end of pregnancy, the fetus must take the journey of childbirth to leave the reproductive mother. Upon its entry to the air-breathing world, the newborn must begin to adjust to life outside the uterus. This is true for all viviparous animals; this article discusses humans as the most-researched example.

A pulmonary artery catheter (PAC), also known as a Swan-Ganz catheter or right heart catheter, is a balloon-tipped catheter that is inserted into a pulmonary artery in a procedure known as pulmonary artery catheterization or right heart catheterization. Pulmonary artery catheterization is a useful measure of the overall function of the heart particularly in those with complications from heart failure, heart attack, arrythmias or pulmonary embolism. It is also a good measure for those needing intravenous fluid therapy, for instance post heart surgery, shock, and severe burns. The procedure can also be used to measure pressures in the heart chambers.

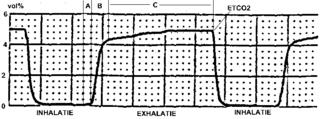

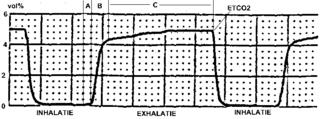

Capnography is the monitoring of the concentration or partial pressure of carbon dioxide (CO

2) in the respiratory gases. Its main development has been as a monitoring tool for use during anesthesia and intensive care. It is usually presented as a graph of CO

2 (measured in kilopascals, "kPa" or millimeters of mercury, "mmHg") plotted against time, or, less commonly, but more usefully, expired volume (known as volumetric capnography). The plot may also show the inspired CO

2, which is of interest when rebreathing systems are being used. When the measurement is taken at the end of a breath (exhaling), it is called "end tidal" CO

2 (PETCO2).

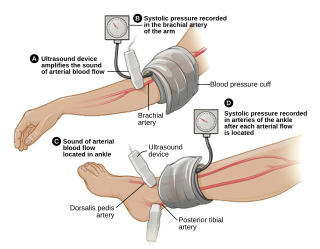

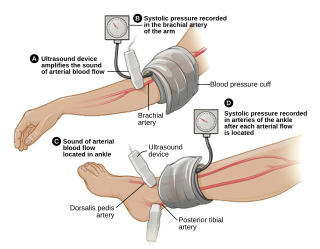

The ankle-brachial pressure index (ABPI) or ankle-brachial index (ABI) is the ratio of the blood pressure at the ankle to the blood pressure in the upper arm (brachium). Compared to the arm, lower blood pressure in the leg suggests blocked arteries due to peripheral artery disease (PAD). The ABPI is calculated by dividing the systolic blood pressure at the ankle by the systolic blood pressure in the arm.

The respiratory rate is the rate at which breathing occurs; it is set and controlled by the respiratory center of the brain. A person's respiratory rate is usually measured in breaths per minute.

Pediatric advanced life support (PALS) is a course offered by the American Heart Association (AHA) for health care providers who take care of children and infants in the emergency room, critical care and intensive care units in the hospital, and out of hospital. The course teaches healthcare providers how to assess injured and sick children and recognize and treat respiratory distress/failure, shock, cardiac arrest, and arrhythmias.

Oxygen saturation is the fraction of oxygen-saturated haemoglobin relative to total haemoglobin in the blood. The human body requires and regulates a very precise and specific balance of oxygen in the blood. Normal arterial blood oxygen saturation levels in humans are 96–100 percent. If the level is below 90 percent, it is considered low and called hypoxemia. Arterial blood oxygen levels below 80 percent may compromise organ function, such as the brain and heart, and should be promptly addressed. Continued low oxygen levels may lead to respiratory or cardiac arrest. Oxygen therapy may be used to assist in raising blood oxygen levels. Oxygenation occurs when oxygen molecules enter the tissues of the body. For example, blood is oxygenated in the lungs, where oxygen molecules travel from the air and into the blood. Oxygenation is commonly used to refer to medical oxygen saturation.

The cardiovascular examination is a portion of the physical examination that involves evaluation of the cardiovascular system. The exact contents of the examination will vary depending on the presenting complaint but a complete examination will involve the heart, lungs, belly and the blood vessels.

In medicine, monitoring is the observation of a disease, condition or one or several medical parameters over time.

The article reviews the evolution of continuous noninvasive arterial pressure measurement (CNAP). The historical gap between ease of use, but intermittent upper arm instruments and bulky, but continuous “pulse writers” (sphygmographs) is discussed starting with the first efforts to measure pulse, published by Jules Harrison in 1835. Such sphygmographs led a shadowy existence in the past, while Riva Rocci's upper arm blood pressure measurement started its triumphant success over 100 years ago. In recent times, CNAP measurement introduced by Jan Penáz in 1973 enabled the first recording of noninvasive beat-to-beat blood pressure resulting in marketed products such as the Finapres™ device and its successors. Recently, a novel method for CNAP monitoring has been designed for patient monitoring in perioperative, critical and emergency care, where blood pressure needs to be measured repeatedly or even continuously to facilitate the best care for patients.

Arterial blood pressure is most commonly measured via a sphygmomanometer, which historically used the height of a column of mercury to reflect the circulating pressure. Blood pressure values are generally reported in millimetres of mercury (mmHg), though aneroid and electronic devices do not contain mercury.