Lungfish are freshwater vertebrates belonging to the Superorder Dipnoi. Lungfish are best known for retaining ancestral characteristics within the Osteichthyes, including the ability to breathe air, and ancestral structures within Sarcopterygii, including the presence of lobed fins with a well-developed internal skeleton. Lungfish represent the closest living relatives of the tetrapods. The mouths of lungfish typically bear tooth plates, which are used to crush hard shelled organisms.

Sarcopterygii — sometimes considered synonymous with Crossopterygii — is a taxon of the bony fish known as the lobe-finned fish or sarcopterygians, characterised by prominent muscular limb buds (lobes) within the fins, which are supported by articulated appendicular skeletons. This is in contrast to the other clade of bony fish, the Actinopterygii, which have only skin-covered bony spines (lepidotrichia) supporting the fins.

The maxilla in vertebrates is the upper fixed bone of the jaw formed from the fusion of two maxillary bones. In humans, the upper jaw includes the hard palate in the front of the mouth. The two maxillary bones are fused at the intermaxillary suture, forming the anterior nasal spine. This is similar to the mandible, which is also a fusion of two mandibular bones at the mandibular symphysis. The mandible is the movable part of the jaw.

Rhipidistia, also known as Dipnotetrapodomorpha, is a clade of lobe-finned fishes which includes the tetrapods and lungfishes. Rhipidistia formerly referred to a subgroup of Sarcopterygii consisting of the Porolepiformes and Osteolepiformes, a definition that is now obsolete. However, as cladistic understanding of the vertebrates has improved over the last few decades, a monophyletic Rhipidistia is now understood to include the whole of Tetrapoda and the lungfishes.

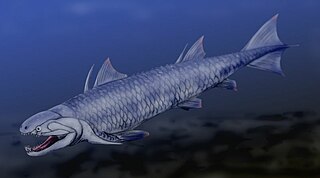

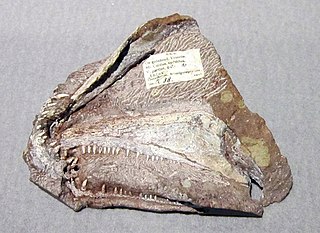

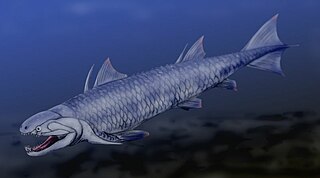

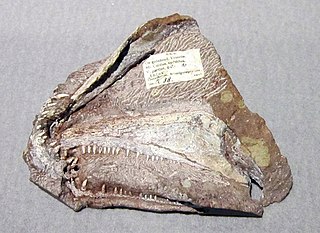

Eusthenopteron is a genus of prehistoric sarcopterygian which has attained an iconic status from its close relationships to tetrapods. Early depictions of this animal show it emerging onto land; however, paleontologists now widely agree that it was a strictly aquatic animal. The genus Eusthenopteron is known from several species that lived during the Late Devonian period, about 385 million years ago. Eusthenopteron was first described by J. F. Whiteaves in 1881, as part of a large collection of fishes from Miguasha, Quebec. Some 2,000 Eusthenopteron specimens have been collected from Miguasha, one of which was the object of intensely detailed study and several papers from the 1940s to the 1990s by paleoichthyologist Erik Jarvik.

Panderichthys is a genus of extinct sarcopterygian from the late Devonian period, about 380 Mya. Panderichthys, which was recovered from Frasnian deposits in Latvia, is represented by two species. P. stolbovi is known only from some snout fragments and an incomplete lower jaw. P. rhombolepis is known from several more complete specimens. Although it probably belongs to a sister group of the earliest tetrapods, Panderichthys exhibits a range of features transitional between tristichopterid lobe-fin fishes and early tetrapods. It is named after the German-Baltic paleontologist Christian Heinrich Pander. Possible tetrapod tracks dating back to before the appearance of Panderichthys in the fossil record were reported in 2010, which suggests that Panderichthys is not a direct ancestor of tetrapods, but nonetheless shows the traits that evolved during the fish-tetrapod evolution

The choanae, posterior nasal apertures or internal nostrils are two openings found at the back of the nasal passage between the nasal cavity and the pharynx, in humans and other mammals. They are considered one of the most important synapomorphies of tetrapodomorphs, that allowed the passage from water to land.

The Tetrapodomorpha are a clade of vertebrates consisting of tetrapods and their closest sarcopterygian relatives that are more closely related to living tetrapods than to living lungfish. Advanced forms transitional between fish and the early labyrinthodonts, such as Tiktaalik, have been referred to as "fishapods" by their discoverers, being half-fish, half-tetrapods, in appearance and limb morphology. The Tetrapodomorpha contains the crown group tetrapods and several groups of early stem tetrapods, which includes several groups of related lobe-finned fishes, collectively known as the osteolepiforms. The Tetrapodomorpha minus the crown group Tetrapoda are the stem Tetrapoda, a paraphyletic unit encompassing the fish to tetrapod transition.

Ventastega is an extinct genus of stem tetrapod that lived during the Upper Fammenian of the Late Devonian, approximately 372.2 to 358.9 million years ago. Only one species is known that belongs in the genus, Ventastega curonica, which was described in 1996 after fossils were discovered in 1933 and mistakenly associated with a fish called Polyplocodus wenjukovi. ‘Curonica’ in the species name refers to Curonia, the Latin name for Kurzeme, a region in western Latvia. Ventastega curonica was discovered in two localities in Latvia, and was the first stem tetrapod described in Latvia along with being only the 4th Devonian tetrapodomorph known at the time of description. Based on the morphology of both cranial and post-cranial elements discovered, Ventastega is more primitive than other Devonian tetrapodomorphs including Acanthostega and Ichthyostega, and helps further understanding of the fish-tetrapod transition.

Rhizodontida is an extinct group of predatory tetrapodomorphs known from many areas of the world from the Givetian through to the Pennsylvanian - the earliest known species is about 377 million years ago (Mya), the latest around 310 Mya. Rhizodonts lived in tropical rivers and freshwater lakes and were the dominant predators of their age. They reached huge sizes - the largest known species, Rhizodus hibberti from Europe and North America, was an estimated 7 m in length, making it the largest freshwater fish known.

Psarolepis is a genus of extinct bony fish which lived around 397 to 418 million years ago. Fossils of Psarolepis have been found mainly in South China and described by paleontologist Xiaobo Yu in 1998. It is not known certainly in which group Psarolepis belongs, but paleontologists agree that it probably is a basal genus and seems to be close to the common ancestor of lobe-finned and ray-finned fishes. In 2001, paleontologist John A. Long compared Psarolepis with onychodontiform fishes and refer to their relationships.

Diabolepis is an extinct genus of very primitive lungfish which lived about 400 million years ago, in the Early Devonian period of South China. Diabolepis is the most basal known dipnoan.

Colosteidae is a family of stegocephalians that lived in the Carboniferous period. They possessed a variety of characteristics from different tetrapod or stem-tetrapod groups, which made them historically difficult to classify. They are now considered to be part of a lineage intermediate between the earliest Devonian terrestrial vertebrates, and the different groups ancestral to all modern tetrapods, such as temnospondyls and reptiliomorphs.

Elpistostegalia or Panderichthyida is an order of prehistoric lobe-finned fishes which lived during the Middle Devonian to Late Devonian period. They represent the advanced tetrapodomorph stock, the fishes more closely related to tetrapods than the osteolepiform fishes. The earliest elpistostegalians, combining fishlike and tetrapod-like characters, are sometimes called fishapods, a phrase coined for the advanced elpistostegalian Tiktaalik. Through a strict cladistic view, the order includes the terrestrial tetrapods.

Megalichthyidae is an extinct family of tetrapodomorphs which lived from the Middle–Late Devonian to the Early Permian. They are known primarily from freshwater deposits, mostly in the Northern Hemisphere, but one genus (Cladarosymblema) is known from Australia, and the possible megalichthyid Mahalalepis is from Antarctica.

The skull roof or the roofing bones of the skull are a set of bones covering the brain, eyes and nostrils in bony fishes and all land-living vertebrates. The bones are derived from dermal bone and are part of the dermatocranium.

Ymeria is an extinct genus of early stem tetrapod from the Devonian of Greenland. Of the two other genera of stem tetrapods from Greenland, Acanthostega and Ichthyostega, Ymeria is most closely related to Ichthyostega, though the single known specimen is smaller, the skull about 10 cm in length. A single interclavicle resembles that of Ichthyostega, an indication Ymeria may have resembled this genus in the post-cranial skeleton.

Tinirau is an extinct genus of sarcopterygian fish from the Middle Devonian of Nevada. Although it spent its entire life in the ocean, Tinirau is a stem tetrapod close to the ancestry of land-living vertebrates in the crown group Tetrapoda. Relative to more well-known stem tetrapods, Tinirau is more closely related to Tetrapoda than is Eusthenopteron, but farther from Tetrapoda than is Panderichthys. The type and only species of Tinirau is T. clackae, named in 2012.

The evolution of tetrapods began about 400 million years ago in the Devonian Period with the earliest tetrapods evolved from lobe-finned fishes. Tetrapods are categorized as animals in the biological superclass Tetrapoda, which includes all living and extinct amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals. While most species today are terrestrial, little evidence supports the idea that any of the earliest tetrapods could move about on land, as their limbs could not have held their midsections off the ground and the known trackways do not indicate they dragged their bellies around. Presumably, the tracks were made by animals walking along the bottoms of shallow bodies of water. The specific aquatic ancestors of the tetrapods, and the process by which land colonization occurred, remain unclear. They are areas of active research and debate among palaeontologists at present.

Innovations conventionally associated with terrestrially first appeared in aquatic elpistostegalians such as Panderichthys rhombolepis, Elpistostege watsoni, and Tiktaalik roseae. Phylogenetic analyses distribute the features that developed along the tetrapod stem and display a stepwise process of character acquisition, rather than abrupt. The complete transition occurred over a period of 30 million years beginning with the tetrapodomorph diversification in the Middle Devonian.