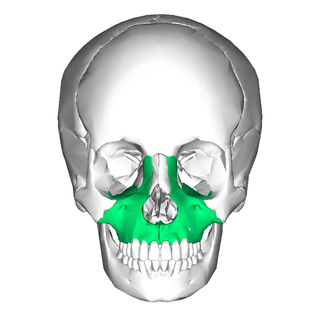

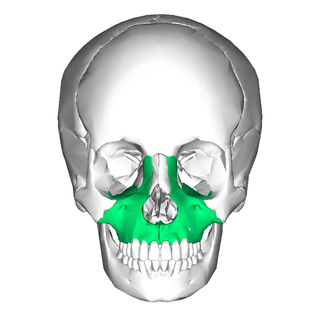

In vertebrates, the maxilla is the upper fixed bone of the jaw formed from the fusion of two maxillary bones. In humans, the upper jaw includes the hard palate in the front of the mouth. The two maxillary bones are fused at the intermaxillary suture, forming the anterior nasal spine. This is similar to the mandible, which is also a fusion of two mandibular bones at the mandibular symphysis. The mandible is the movable part of the jaw.

The jaws are a pair of opposable articulated structures at the entrance of the mouth, typically used for grasping and manipulating food. The term jaws is also broadly applied to the whole of the structures constituting the vault of the mouth and serving to open and close it and is part of the body plan of humans and most animals.

In the human skull, the zygomatic bone, also called cheekbone or malar bone, is a paired irregular bone, situated at the upper and lateral part of the face and forms part of the lateral wall and floor of the orbit, of the temporal fossa and the infratemporal fossa. It presents a malar and a temporal surface; four processes, and four borders.

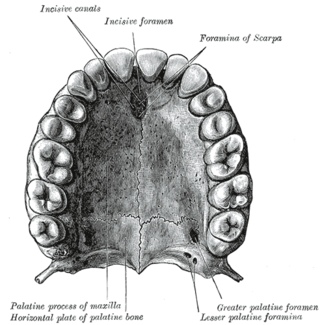

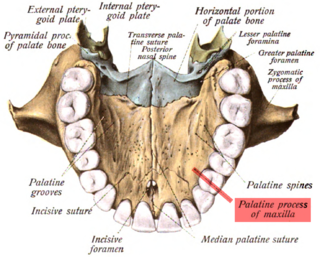

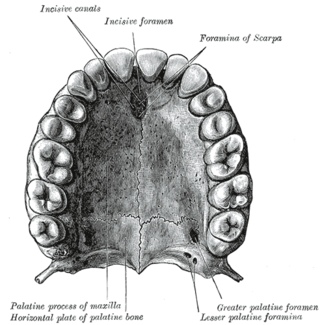

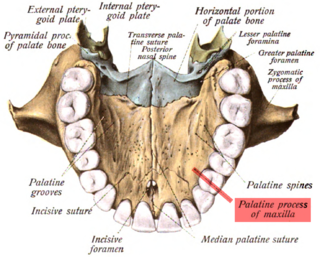

In anatomy, the palatine bones are two irregular bones of the facial skeleton in many animal species, located above the uvula in the throat. Together with the maxilla, they comprise the hard palate.

The vomer is one of the unpaired facial bones of the skull. It is located in the midsagittal line, and articulates with the sphenoid, the ethmoid, the left and right palatine bones, and the left and right maxillary bones. The vomer forms the inferior part of the nasal septum in humans, with the superior part formed by the perpendicular plate of the ethmoid bone. The name is derived from the Latin word for a ploughshare and the shape of the bone.

Galesaurus is an extinct genus of carnivorous cynodont therapsid that lived between the Induan and the Olenekian stages of the Early Triassic in what is now South Africa. It was incorrectly classified as a dinosaur by Sir Richard Owen in 1859.

In the human mouth, the incisive foramen is the opening of the incisive canals on the hard palate immediately behind the incisor teeth. It gives passage to blood vessels and nerves. The incisive foramen is situated within the incisive fossa of the maxilla.

Continuous with the dorsal end of the first pharyngeal arch, and growing forward from its cephalic border, is a triangular process, the maxillary prominence, the ventral extremity of which is separated from the mandibular arch by a ">"-shaped notch.

In human anatomy of the mouth, the palatine process of maxilla, is a thick, horizontal process of the maxilla. It forms the anterior three quarters of the hard palate, the horizontal plate of the palatine bone making up the rest. It is the most important bone in the midface. It provides structural support for the viscerocranium.

Chimaerasuchus is an extinct genus of Chinese crocodyliform from the Early Cretaceous Wulong Formation. The four teeth in the very tip of its short snout gave it a "bucktoothed" appearance. Due its multicusped teeth and marked heterodonty, it is believed to have been an herbivore. Chimaerasuchus was originally discovered in the 1960s but not identified as a crocodyliform until 1995, instead thought to possibly be a multituberculate mammal. It is highly unusual, as only two other crocodyliforms have displayed any characteristics resembling its adaptations to herbivory.

The frontonasal process, or frontonasal prominence is one of the five swellings that develop to form the face. The frontonasal process is unpaired, and the others are the paired maxillary prominences, and the paired mandibular prominences. During the fourth week of embryonic development, an area of thickened ectoderm develops, on each side of the frontonasal process called the nasal placodes or olfactory placodes, and appear immediately under the forebrain.

Around the 5th week, the intermaxillary segment arises as a result of fusion of the two medial nasal processes and the frontonasal process within the embryo. The intermaxillary segment gives rise to the primary palate. The primary palate will form the premaxillary portion of the maxilla. This small portion is anterior to the incisive foramen and will contain the maxillary incisors.

The human nose is the first organ of the respiratory system. It is also the principal organ in the olfactory system. The shape of the nose is determined by the nasal bones and the nasal cartilages, including the nasal septum, which separates the nostrils and divides the nasal cavity into two.

Xixiasaurus is a genus of troodontid dinosaur that lived during the Late Cretaceous Period in what is now China. The only known specimen was discovered in Xixia County, Henan Province, in central China, and became the holotype of the new genus and species Xixiasaurus henanensis in 2010. The names refer to the areas of discovery, and can be translated as "Henan Xixia lizard". The specimen consists of an almost complete skull, part of the lower jaw, and teeth, as well as a partial right forelimb.

Herpetoskylax is an extinct genus of biarmosuchians which existed in South Africa. The type species is Herpetoskylax hopsoni. It lived in the Late Permian Period.

Yonghesuchus is an extinct genus of Late Triassic archosaur reptile. Remains have been found from the early Late Triassic Tongchuan Formation in Shanxi, China. It is named after Yonghe County, the county where fossils were found. Currently only one species, Y. sangbiensis, is known. The specific name refers to Sangbi Creek, as fossils were found in one of its banks.

Ovoo gurvel is an extinct varanid lizard from the Late Cretaceous of Mongolia. It is one of the smallest and earliest monitor lizards. It was described in 2008. Ovoo possesses a pair of small bones in its skull that are not seen in any other lizard.

The face and neck development of the human embryo refers to the development of the structures from the third to eighth week that give rise to the future head and neck. They consist of three layers, the ectoderm, mesoderm and endoderm, which form the mesenchyme, neural crest and neural placodes. The paraxial mesoderm forms structures named somites and somitomeres that contribute to the development of the floor of the brain and voluntary muscles of the craniofacial region. The lateral plate mesoderm consists of the laryngeal cartilages. The three tissue layers give rise to the pharyngeal apparatus, formed by six pairs of pharyngeal arches, a set of pharyngeal pouches and pharyngeal grooves, which are the most typical feature in development of the head and neck. The formation of each region of the face and neck is due to the migration of the neural crest cells which come from the ectoderm. These cells determine the future structure to develop in each pharyngeal arch. Eventually, they also form the neurectoderm, which forms the forebrain, midbrain and hindbrain, cartilage, bone, dentin, tendon, dermis, pia mater and arachnoid mater, sensory neurons, and glandular stroma.

Arisierpeton is an extinct genus of synapsids from the Early Permian Garber Formation of Richards Spur, Oklahoma. It contains a single species, Arisierpeton simplex.

Nyaphulia is an extinct genus of dicynodont therapsid from the middle Permian of South Africa, containing only the type species N. oelofseni. The generic name is in honour of John Nyaphuli of the National Museum of Bloemfontein, who contributed extensively to South African palaeontology and discovered the holotype specimen of Nyaphulia in 1982. Nyaphulia was initially named as a second species of the basal dicynodont Eodicynodon by Professor Bruce Rubidge in 1990 as E. oelofseni, named after his mentor in palaeontology and geology Dr. Burger Oelofsen.