Georgian is the most widely spoken Kartvelian language; it also serves as the literary language or lingua franca for speakers of related languages. It is the official language of Georgia and the native or primary language of 87.6% of its population. Its speakers today amount to approximately four million. Georgian is written in its own unique alphabet.

Guttural speech sounds are those with a primary place of articulation near the back of the oral cavity, where it is difficult to distinguish a sound's place of articulation and its phonation. In popular usage it is an imprecise term for sounds produced relatively far back in the vocal tract, such as German ch or the Arabic ayin, but not simple glottal sounds like h. The term 'guttural language' is used for languages that have such sounds.

In phonetics, ejective consonants are usually voiceless consonants that are pronounced with a glottalic egressive airstream. In the phonology of a particular language, ejectives may contrast with aspirated, voiced and tenuis consonants. Some languages have glottalized sonorants with creaky voice that pattern with ejectives phonologically, and other languages have ejectives that pattern with implosives, which has led to phonologists positing a phonological class of glottalic consonants, which includes ejectives.

The Georgians, or Kartvelians, are a nation and indigenous Caucasian ethnic group native to Georgia and the South Caucasus. Georgian diaspora communities are also present throughout Russia, Turkey, Greece, Iran, Ukraine, United States, and European Union.

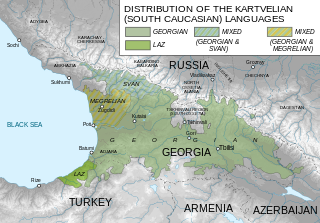

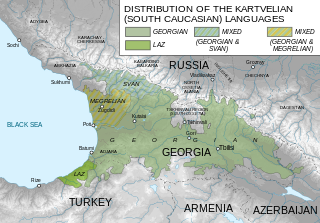

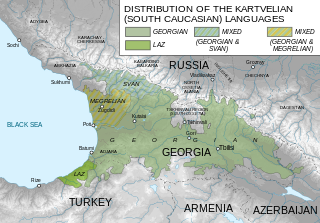

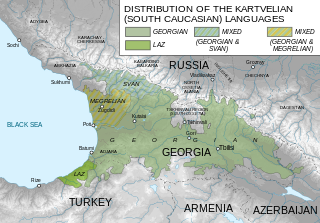

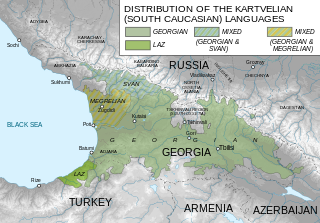

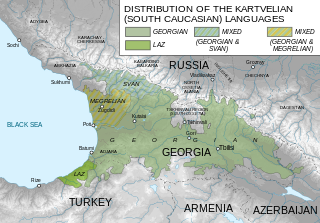

The Laz language or Lazuri is a Kartvelian language spoken by the Laz people on the southeastern shore of the Black Sea. In 2007, it was estimated that there were around 20,000 native speakers in Turkey, in a strip of land extending from Melyat to the Georgian border, and around 1,000 native speakers around Adjara in Georgia. There are also around 1,000 native speakers of Laz in Germany.

Mingrelian or Megrelian is a Kartvelian language spoken in Western Georgia, primarily by the Mingrelians. The language was also called Kolkhuri in the early 20th century. Mingrelian has historically been only a regional language within the boundaries of historical Georgian states and then modern Georgia, and the number of younger people speaking it has decreased substantially, with UNESCO designating it as a "definitely endangered language".

Svan is a Kartvelian language spoken in the western Georgian region of Svaneti primarily by the Svan people. With its speakers variously estimated to be between 30,000 and 80,000, the UNESCO designates Svan as a "definitely endangered language". It is of particular interest because it has retained many features that have been lost in the other Kartvelian languages.

Implosive consonants are a group of stop consonants with a mixed glottalic ingressive and pulmonic egressive airstream mechanism. That is, the airstream is controlled by moving the glottis downward in addition to expelling air from the lungs. Therefore, unlike the purely glottalic ejective consonants, implosives can be modified by phonation. Contrastive implosives are found in approximately 13% of the world's languages.

Georgian grammar has many distinctive and extremely complex features, such as split ergativity and a polypersonal verb agreement system.

The phonology of the Persian language varies between regional dialects, standard varieties, and even from older variates of Persian. Persian is a pluricentric language and countries that have Persian as an official language have separate standard varieties, namely: Standard Dari (Afghanistan), Standard Iranian Persian and Standard Tajik (Tajikistan). The most significant differences between standard varieties of Persian are their vowel systems. Standard varieties of Persian have anywhere from 6 to 8 vowel distinctions, and similar vowels may be pronounced differently between standards. However, there are not many notable differences when comparing consonants, as all standard varieties a similar amount of consonant sounds. Though, colloquial varieties generally have more differences than their standard counterparts. Most dialects feature contrastive stress and syllable-final consonant clusters.

Georgian is a Kartvelian language spoken by about 4 million people, primarily in Georgia but also by indigenous communities in northern Turkey and Azerbaijan, and the diaspora, such as in Russia, Turkey, Iran, Europe, and North America. It is a highly standardized language, with established literary and linguistic norms dating back to the 5th century.

Yeyi is a Bantu language spoken by many of the approximately 50,000 Yeyi people along the Okavango River in Namibia and Botswana. Yeyi, influenced by Juu languages, is one of several Bantu languages along the Okavango with clicks. Indeed, it has the largest known inventory of clicks of any Bantu language, with dental, alveolar, palatal, and lateral articulations. Though most of its older speakers prefer Yeyi in normal conversation, it is being gradually phased out in Botswana by a popular move towards Tswana, with Yeyi only being learned by children in a few villages. Yeyi speakers in the Caprivi Strip of north-eastern Namibia, however, retain Yeyi in villages, but may also speak the regional lingua franca, Lozi.

Garre is an Afro-Asiatic language spoken by the Garre people inhabiting southern Somalia, Ethiopia and northern Kenya. It belongs to the family's Cushitic branch, and had an estimated 50,000 speakers in Somalia in 1998, 57,500 in 2006 and 83,600 in 2019. The total number of speakers in Kenya and Somalia was estimated at 685,600 in 2019. Garre language is considered an ancient Somali dialect. Af-Garre is in the Digil classification of Somali dialects. Garre language is readily intelligible to Digil speakers as it has some affinity with Af-Maay and Af-Boon.

The Proto-Kartvelian language, or Common Kartvelian, is the linguistic reconstruction of the common ancestor of the Kartvelian languages, which was spoken by the ancestors of the modern Kartvelian peoples. The existence of such a language is widely accepted by specialists in linguistics, who have reconstructed a broad outline of the language by comparing the existing Kartvelian languages against each other. Several linguists, namely, Gerhard Deeters and Georgy Klimov have also reconstructed a lower-level proto-language called Proto-Karto-Zan or Proto-Georgian-Zan, which is the ancestor of Karto-Zan languages.

The Kartvelian languages are a language family indigenous to the South Caucasus and spoken primarily in Georgia. There are approximately 5.2 million Kartvelian speakers worldwide, with large groups in Russia, Iran, the United States, the European Union, Israel, and northeastern Turkey. The Kartvelian family has no known relation to any other language family, making it one of the world's primary language families.

The Zan languages, or Zanuri or Colchidian, are a branch of the Kartvelian languages constituted by the Mingrelian and Laz languages. The grouping is disputed as some Georgian linguists consider the two to form a dialect continuum of one Zan language. This is often challenged on the most commonly applied criteria of mutual intelligibility when determining borders between languages, as Mingrelian and Laz are only partially mutually intelligible, though speakers of one language can recognize a sizable amount of vocabulary of the other, primarily due to semantic loans, lexical loans and other areal features resulting from geographical proximity and historical close contact common for dialect continuums.

Mingrelian is a Kartvelian language that is mainly spoken in the Western Georgian regions Samegrelo and Abkhazia. In Abkhazia the number of Mingrelian speakers declined dramatically in the 1990s as a result of heavy ethnic cleansing of ethnic Georgians, the overwhelming majority of which were Mingrelians.

This article discusses the phonology of the Inuit languages. Unless otherwise noted, statements refer to Inuktitut dialects of Canada.

Mengen and Poeng are rather divergent dialects of an Austronesian language of New Britain in Papua New Guinea.

Adyghe is a language of the Northwest Caucasian family which, like the other Northwest Caucasian languages, is very rich in consonants, featuring many labialized and ejective consonants. Adyghe is phonologically more complex than Kabardian, having the retroflex consonants and their labialized forms.