Nepali grammar is the study of the morphology and syntax of Nepali, an Indo-European language spoken in South Asia.

Nepali grammar is the study of the morphology and syntax of Nepali, an Indo-European language spoken in South Asia.

In matters of script, Nepali uses Devanagari. On this grammar page Nepali is written in "standard orientalist" transcription as outlined in Masica (1991 :xv). Being "primarily a system of transliteration from the Indian scripts, [and] based in turn upon Sanskrit" (cf. IAST), these are its salient features: subscript dots for retroflex consonants; macrons for etymologically, contrastively long vowels; h denoting aspirated plosives. Tildes denote nasalized vowels.

Vowels and consonants are outlined in the tables below. Hovering the mouse cursor over them will reveal the appropriate IPA symbol, while in the rest of the article hovering the mouse cursor over underlined forms will reveal the appropriate English translation.

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Like Bengali, Assamese, and Marathi and unlike Hindustani, Nepali may retain the final schwa in a word. The following rules can be followed to figure out whether or not Nepali words retain the final schwa.

1) Schwa is retained if the final syllable is a conjunct consonant. अन्त (anta, 'end'), सम्बन्ध (sambandha, 'relation'), श्रेष्ठ (śreṣṭha, 'greatest'/a last name).

Exceptions: conjuncts such as ञ्चञ्ज in मञ्च (mañc, 'stage') गञ्ज (gañj, 'city') and occasionally the last name पन्त (panta/pant).

2) For any verb form the final schwa is always retained unless the schwa-cancelling halanta is present. हुन्छ (huncha, 'it happens'), भएर (bhaera, 'in happening so; therefore'), गएछ(gaecha, 'he apparently went'), but छन् (chan, 'they are'), गईन् (gain, 'she went').

Meanings may change with the wrong orthography: गईन (gaina, 'she didn't go') vs गईन् (gain, 'she went').

3) Adverbs, onomatopoeia and postpositions usually maintain the schwa and if they don't, halanta is acquired: अब (aba 'now'), तिर (tira, 'towards'), आज (āja, 'today') सिम्सिम (simsim 'drizzle') vs झन् (jhan, 'more').

4) Few exceptional nouns retain the schwa such as: दुख(dukha, 'suffering'), सुख (sukha, 'pleasure').

Note: Schwas are often retained in music and poetry to facilitate singing and recitation.

Nepali nouns that denote male and female beings are sometimes distinguished by suffixation or through pairs of lexically differing terms. [1] Thus one pattern involves masculine -o/ā vs feminine -ī suffixes (e.g. chorā "son" : chorī "daughter", buṛho "old man" : buṛhī "old woman"), while another such phenomenon is that of the derivational feminine suffix -nī (e.g. chetrī "Chetri" : chetrīnī "Chetri woman", kukur "dog" : kukurnī "female dog"). Beyond this, nouns are otherwise not overtly marked (i.e. inanimate nouns, abstract nouns, all other animates).

Overall, in terms of grammatical gender, among Indo-Aryan languages, Nepali possesses an "attenuated gender" system, in which "gender accord typically is restricted to female animates (so that the system is essentially restructured as zero/+Fem), optional or loose even then […], and greatly reduced in syntactic scope. […] In Nepali, the [declensional] ending is a neutral -o, changeable to -ī with Personal Feminines in more formal style." [2]

Nepali distinguishes two numbers, with a common pluralizing suffix for nouns in -harū (e.g. mitra "friend" : mitraharū "friends"). Unlike the English plural it is not mandatory, and may be left unexpressed if plurality is already indicated in some other way: e.g. by explicit numbering, or agreement. Riccardi (2003 :554) further notes that the suffix "rarely indicates simple plurality: it often means that other objects of the same or a like class are also indicated and may be translated as 'and other things'."

Adjectives may be divided into declinable and indeclinable categories. Declinables are marked, through termination, for the gender and number of the nouns they qualify. The declinable endings are -o for the "masculine" singular, -ī for the feminine singular, and -ā for the plural. e.g. sāno kitāb "small book", sānī keṭī "small girl", sānā kalamharū "small pens".

"Masculine", or rather "neutral" -o is the citation form and the otherwise overwhelmingly more encountered declension, as previously noted, gender in Nepali is attenuated and accord "typically is restricted to female animates", and "optional or loose even then". However, "In writing, there has been a strong tendency by some to extend the use of feminine markers beyond their use in speech to include the consistent marking of certain adjectives with feminine endings. This tendency is strengthened by some Nepali grammars and may be reinforced by the influence of Hindi upon both speech and writing." [3]

Indeclinable adjectives are completely invariable, and can end in either consonants or vowels (except -o).

In Nepali the locus of grammatical function or "case-marking" lies within a system of agglutinative suffixes or particles known as postpositions, which parallel English's prepositions. There is a number of such one-word primary postpositions:

Beyond this come compound postpositions, composed of a primary postposition (most likely ko or bhandā) plus an adverb.

Nepali has personal pronouns for the first and second persons, while third person forms are of demonstrative origin, and can be categorized deictically as proximate and distal. The pronominal system is quite elaborate, by reason of its differentiation on lines of sociolinguistic formality. In this respect it has three levels or grades of formality/status: low, middle, and high (see T-V distinction for further clarification). Pronouns do not distinguish gender.

The first person singular pronoun is मma, and the first person plural is हामीhāmī. The following table lists the second and third person singular forms.

| 2nd pn. | 3rd pn. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prox. | Dist. | |||

| Low | तँ tã | यो yo( यस yas) | त्यो tyo( त्यस tyas) | ऊ ū( उस us) |

| Middle | तिमी timī | यिनी yinī( यिन yin) | तिनी tinī( तिन tin) | उनी unī( उन un) |

| High | तपाईं tapāī̃ | यहाँ yahā̃ | वहाँ wahā̃ | |

yo and tyo have yī and tī as plurals, while other pronouns pluralize (including hāmī, for emphasis, but excluding ū) with the common suffix -harū. Also, bracketed beside of a number of forms in the above chart are their oblique counterparts, used when they (as demonstrative pronouns) or that which they qualify (as demonstrative determiners) are followed by a postposition. However, the need to oblique weakens the longer distance between demonstrative and postposition gets. Also, one exception which does not require obliquing is -sãga "with".

Verbs in Nepali are quite highly inflected, agreeing with the subject in number, gender, status and person. They also inflect for tense, mood, and aspect. As well as these inflected finite forms, there are also a large number of participial forms.

Possibly the most important verb in Nepali, as well as the most irregular, is the verb हुनु hunu 'to be, to become'. In the simple present tense, there are at least three conjugations of हुनु hunu, only one of which is regular. The first, the ho-conjugation is, broadly speaking, used to define things, and as such its complement is usually a noun. The second, the cha-conjugation is used to describe things, and the complement is usually an adjectival or prepositional phrase. The third, the huncha-conjugation, is used to express regular occurrences or future events, and also expresses 'to become' or 'to happen'.

They are conjugated as follows:

| हो ho | छ cha | हुन्छ huncha | |

|---|---|---|---|

| First person singular | हुँ hũ | छु chu | हुन्छु hunchu |

| First person plural | हौँ haũ | छौँ chaũ | हुन्छौँ hunchaũ |

| Second person singular low-grade | होस् hos | छस् chas | हुन्छस् hunchas |

| Second person middle-grade/plural | हौ hau | छौ chau | हुन्छौ hunchau |

| High grade | हुनुहन्छ hunuhuncha | हुनुहन्छ hunuhuncha | हुनुहन्छ hunuhuncha |

| Third person singular low-grade | हो ho | छ cha | हुन्छ huncha |

| Third person middle-grade/plural masculine | हुन् hun | छन् chan | हुन्छन् hunchan |

| Third person middle-grade/plural feminine | हुन् hun | छिन् chin | हुन्छिन् hunchin |

हुनु hunu also has two suppletive stems in the simple past, namely भ- bha- (the use of which corresponds to the huncha-conjugation) and थि- thi- (which corresponds to both the cha and ho-conjugations) which are otherwise regularly conjugated. भ- bha- is also the stem used in the formation of the various participles.

The finite forms of regular verbs are conjugated as follows (using गर्नु garnu 'to do' as an example):

| Simple Present/Future | Probable Future | Simple Past | Past Habitual | Injunctive | Imperative | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First person singular | गर्छु garchu 'I (will) do' | गरुँला garũlā 'I will (probably) do' | गरेँ garẽ 'I did' | गर्थेँ garthẽ 'I used to do' | गरुँ garũ 'may I do' | – |

| First person plural | गर्छौँ garchaũ 'We (will) do' | गरौँला garaũlā 'We will (probably) do' | गर्यौ garyaũ 'We did' | गर्थ्यौँ garthyaũ 'We used to do' | गरौँ garaũ 'may we do, let's do' | – |

| Second person singular low-grade | गर्छस् garchas 'you (will) do' | गर्लास् garlās 'you will (probably) do' | गरिस् garis 'you did' | गर्थिस् garthis 'you used to do' | गरेस् gares 'may you do' | गर् gar 'do!' |

| Second person middle-grade/plural | गर्छौ garchau 'you (will) do' | गरौला garaulā 'you will (probably) do' | गर्यौ garyau 'you did' | गर्थ्यौ garthyau 'you used to do' | गरौ garau 'may you do' | गर gara 'do' |

| High grade | गर्नुहुन्छ garnuhuncha 'you (will) do' | गर्नुहोला garnuhola 'you will (probably) do' | गर्नुभयो garnubhayo 'you did' | गर्नुहुन्थ्यो garnuhunthyo 'you used to do' | गर्नुहोस् garnuhos 'may you do, please do' | – |

| Third person singular low-grade | गर्छ garcha 'he does' | गर्ला garlā 'he will (probably) do' | गर्यो garyo 'he did' | गर्थ्यो garthyo 'he used to do' | गरोस् garos 'may he do' | – |

| Third person middle-grade/plural masculine | गर्छन् garchan 'they (will) do' | गर्लान् garlān 'they will (probably) do' | गरे gare 'they did' | गर्थे garthe 'they used to do' | गरून् garūn 'may they do' | – |

| Third person middle-grade/plural feminine | गर्छिन् garchin 'she (will) do' | गर्लिन् garlin 'she will (probably) do' | गरिन् garin 'she did' | गर्थिन् garthin 'she used to do' | गरुन् garūn 'may she do' | – |

As well as these, there are two forms which are infinitival and participial in origin, but are frequently used as if they were finite verbs. Again using गर्नु garnu as an example, these are गरेको gareko 'did' and गर्ने garne 'will do'. Since they are simpler than the conjugated forms, these are often overused by non-native speakers, which can sound stilted.

The eko-participle is also the basis of perfect constructions in Nepali. This is formed by using the auxiliary verb हुनु hunu (usually the cha-form in the present tense and the thi-form in the past) with the eko-participle. So, for example, मैले काम गरेको छु maile kām gareko chu means 'I have done (the) work'.

Nepali has two infinitives. The first is formed by adding -नु nu to the verb stem. This is the citation form of the verb, and is used in a number of constructions, the most important being the construction expressing obligation. This is formed by combining the nu-infinitive with the verb पर्नु parnu 'to fall'. This is an impersonal construction, which means that the object marker -लाई lāī is often added to the agent, unless the verb is transitive, in which case the ergative/instrumental case marker -ले le is added. So, for example, I have to do work would be translated as मैले काम गर्नुपर्छ maile kām garnuparcha. It is also used with the postposition -अघि aghi 'before'. गर्नुअघि garnuaghi, then, means 'before doing'.

The second infinitive is formed by adding -न na to the verb stem. This is used in a wide variety of situations, and can generally be used where the infinitive is used in English. For example, म काम गर्न रामकहाँ गएको थिएँ ma kām garna rāmkahā̃ gaeko thiẽ 'I had gone to Ram's place to do work'.

The Finnish language is spoken by the majority of the population in Finland and by ethnic Finns elsewhere. Unlike the languages spoken in neighbouring countries, such as Swedish and Norwegian, which are North Germanic languages, or Russian, which is a Slavic language, Finnish is a Uralic language of the Finnic languages group. Typologically, Finnish is agglutinative. As in some other Uralic languages, Finnish has vowel harmony, and like other Finnic languages, it has consonant gradation.

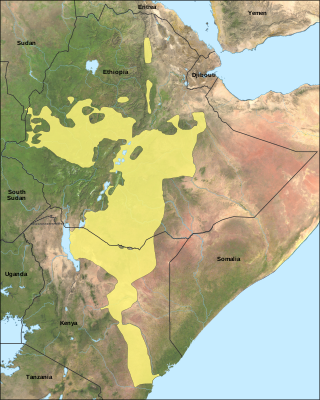

Oromo, historically also called Galla, is an Afroasiatic language that belongs to the Cushitic branch. It is native to the Ethiopian state of Oromia and Northern Kenya and is spoken predominantly by the Oromo people and neighboring ethnic groups in the Horn of Africa. It is used as a lingua franca particularly in the Oromia Region and northeastern Kenya.

Catalan grammar, the morphology and syntax of the Catalan language, is similar to the grammar of most other Romance languages. Catalan is a relatively synthetic, fusional language. Features include:

Bengali grammar is the study of the morphology and syntax of Bengali, an Indo-European language spoken in the Indian subcontinent. Given that Bengali has two forms, চলিত ভাষা and সাধু ভাষা, it is important to note that the grammar discussed below applies fully only to the চলিত (cholito) form. Shadhu bhasha is generally considered outdated and no longer used either in writing or in normal conversation. Although Bengali is typically written in the Bengali script, a romanization scheme is also used here to suggest the pronunciation.

Hindustani, the lingua franca of Northern India and Pakistan, has two standardised registers: Hindi and Urdu. Grammatical differences between the two standards are minor but each uses its own script: Hindi uses Devanagari while Urdu uses an extended form of the Perso-Arabic script, typically in the Nastaʿlīq style.

Eastern Lombard grammar reflects the main features of Romance languages: the word order of Eastern Lombard is usually SVO, nouns are inflected in number, adjectives agree in number and gender with the nouns, verbs are conjugated in tenses, aspects and moods and agree with the subject in number and person. The case system is present only for the weak form of the pronoun.

The grammar of the Gujarati language is the study of the word order, case marking, verb conjugation, and other morphological and syntactic structures of the Gujarati language, an Indo-Aryan language native to the Indian state of Gujarat and spoken by the Gujarati people. This page overviews the grammar of standard Gujarati, and is written in a romanization. Hovering the mouse cursor over underlined forms will reveal the appropriate English translation.

This article discusses the grammar of the Western Lombard (Insubric) language. The examples are in Milanese, written according to the Classical Milanese orthography.

Kurdish grammar has many inflections, with prefixes and suffixes added to roots to express grammatical relations and to form words.

The grammar of the Marathi language shares similarities with other modern Indo-Aryan languages such as Odia, Gujarati or Punjabi. The first modern book exclusively about the grammar of Marathi was printed in 1805 by Willam Carey.

Breton is a Brittonic Celtic language in the Indo-European family, and its grammar has many traits in common with these languages. Like most Indo-European languages it has grammatical gender, grammatical number, articles and inflections and, like the other Celtic languages, Breton has mutations. In addition to the singular–plural system, it also has a singulative–collective system, similar to Welsh. Unlike the other Brittonic languages, Breton has both a definite and indefinite article, whereas Welsh and Cornish lack an indefinite article and unlike the other extant Celtic languages, Breton has been influenced by French.

Somali is an agglutinative language, using many affixes and particles to determine and alter the meaning of words. As in other related Afroasiatic languages, Somali nouns are inflected for gender, number and case, while verbs are inflected for persons, number, tenses, and moods.

Punjabi is an Indo-Aryan language native to the region of Punjab of Pakistan and India and spoken by the Punjabi people. This page discusses the grammar of Modern Standard Punjabi as defined by the relevant sources below.

In linguistic morphology, inflection is a process of word formation in which a word is modified to express different grammatical categories such as tense, case, voice, aspect, person, number, gender, mood, animacy, and definiteness. The inflection of verbs is called conjugation, and one can refer to the inflection of nouns, adjectives, adverbs, pronouns, determiners, participles, prepositions and postpositions, numerals, articles, etc, as declension.

This article deals with the grammar of the Udmurt language.

Old Norse has three categories of verbs and two categories of nouns. Conjugation and declension are carried out by a mix of inflection and two nonconcatenative morphological processes: umlaut, a backness-based alteration to the root vowel; and ablaut, a replacement of the root vowel, in verbs.

Zotung (Zobya) is a language spoken by the Zotung people, in Rezua Township, Chin State, Burma. It is a continuum of closely related dialects and accents. The language does not have a standard written form since it has dialects with multiple variations on its pronunciations. Instead, Zotung speakers use a widely accepted alphabet for writing with which they spell using their respective dialect. However, formal documents are written using the Lungngo dialect because it was the tongue of the first person to prescribe a standard writing, Sir Siabawi Khuamin.

This article concerns the morphology of the Albanian language, including the declension of nouns and adjectives, and the conjugation of verbs. It refers to the Tosk-based Albanian standard regulated by the Academy of Sciences of Albania.

The grammar of Old Saxon is highly inflected, similar to that of Old English or Latin. As an ancient Germanic language, the morphological system of Old Saxon is similar to that of the hypothetical Proto-Germanic reconstruction, retaining many of the inflections thought to have been common in Proto-Indo-European and also including characteristically Germanic constructions such as the umlaut. Among living languages, Old Saxon morphology most closely resembles that of modern High German.

Hindustani verbs conjugate according to mood, tense, person and number. Hindustani inflection is markedly simpler in comparison to Sanskrit, from which Hindustani has inherited its verbal conjugation system. Aspect-marking participles in Hindustani mark the aspect. Gender is not distinct in the present tense of the indicative mood, but all the participle forms agree with the gender and number of the subject. Verbs agree with the gender of the subject or the object depending on whether the subject pronoun is in the dative or ergative case or the nominative case.