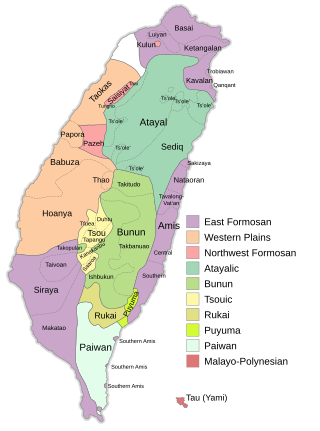

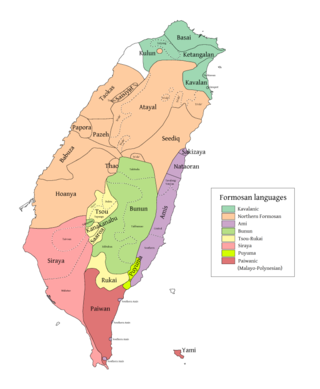

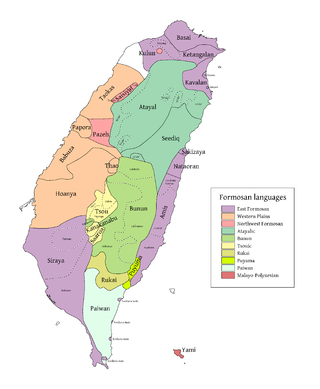

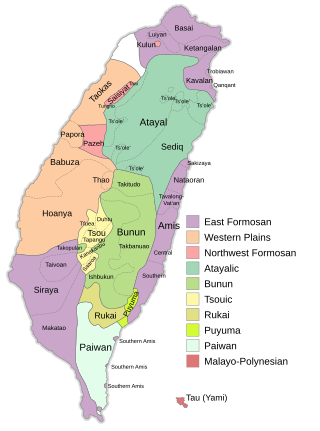

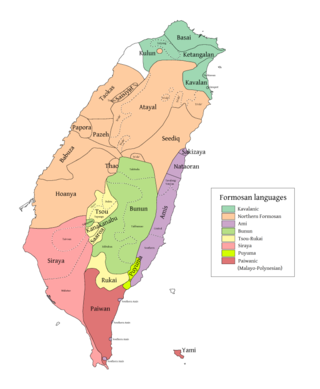

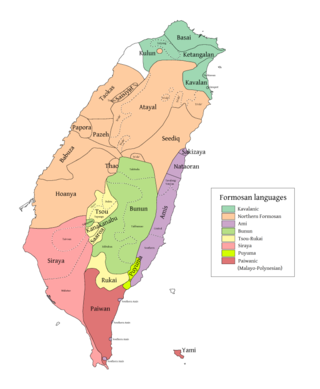

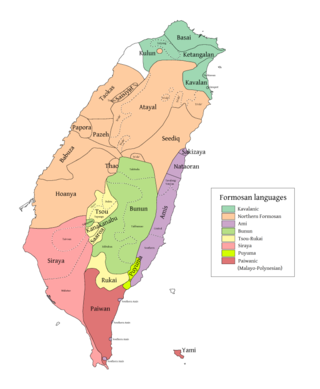

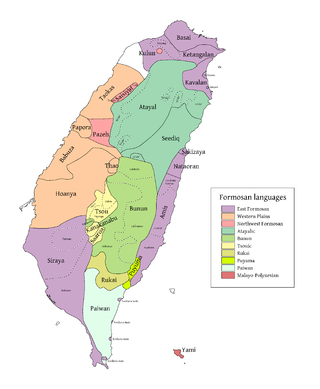

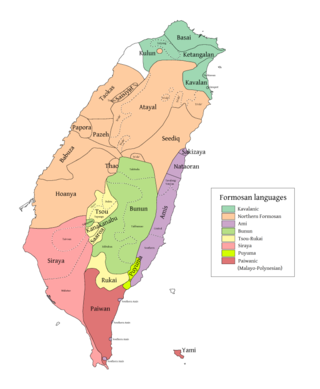

The Formosan languages are a geographic grouping comprising the languages of the indigenous peoples of Taiwan, all of which are Austronesian. They do not form a single subfamily of Austronesian but rather up to nine separate primary subfamilies. The Taiwanese indigenous peoples recognized by the government are about 2.3% of the island's population. However, only 35% speak their ancestral language, due to centuries of language shift. Of the approximately 26 languages of the Taiwanese indigenous peoples, at least ten are extinct, another four are moribund, and all others are to some degree endangered.

Kapampangan, Capampáñgan, or Pampangan is an Austronesian language, and one of the eight major languages of the Philippines. It is the primary and predominant language of the entire province of Pampanga and southern Tarlac, on the southern part of Luzon's central plains geographic region, where the Kapampangan ethnic group resides. Kapampangan is also spoken in northeastern Bataan, as well as in the provinces of Bulacan, Nueva Ecija, and Zambales that border Pampanga. It is further spoken as a second language by a few Aeta groups in the southern part of Central Luzon. The language is known honorifically as Amánung Sísuan.

Tzeltal or Tseltal is a Mayan language spoken in the Mexican state of Chiapas, mostly in the municipalities of Ocosingo, Altamirano, Huixtán, Tenejapa, Yajalón, Chanal, Sitalá, Amatenango del Valle, Socoltenango, Las Rosas, Chilón, San Juan Cancuc, San Cristóbal de las Casas and Oxchuc. Tzeltal is one of many Mayan languages spoken near this eastern region of Chiapas, including Tzotzil, Chʼol, and Tojolabʼal, among others. There is also a small Tzeltal diaspora in other parts of Mexico and the United States, primarily as a result of unfavorable economic conditions in Chiapas.

Basay was a Formosan language spoken around modern-day Taipei in northern Taiwan by the Basay, Qauqaut, and Trobiawan peoples. Trobiawan, Linaw, and Qauqaut were other dialects.

The Bunun language is spoken by the Bunun people of Taiwan. It is one of the Formosan languages, a geographic group of Austronesian languages, and is subdivided in five dialects: Isbukun, Takbunuaz, Takivatan, Takibaka and Takituduh. Isbukun, the dominant dialect, is mainly spoken in the south of Taiwan. Takbunuaz and Takivatan are mainly spoken in the center of the country. Takibaka and Takituduh both are northern dialects. A sixth dialect, Takipulan, became extinct in the 1970s.

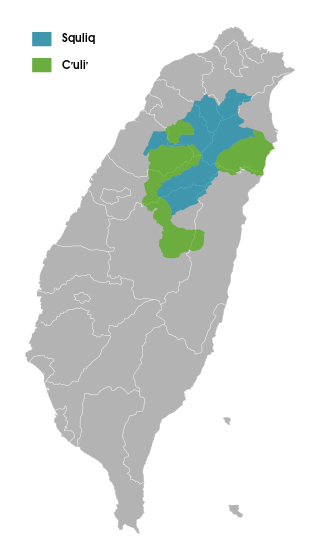

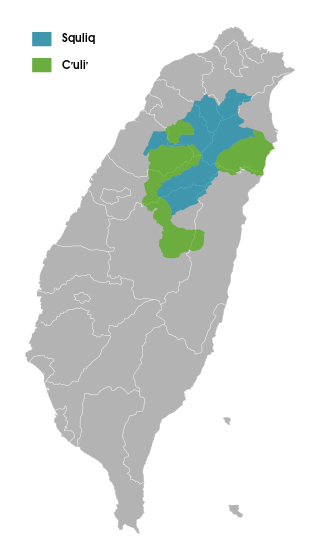

The Atayal language is an Austronesian language spoken by the Atayal people of Taiwan. Squliq and C’uli’ (Ts’ole’) are two major dialects. Mayrinax and Pa’kuali’, two subdialects of C’uli’, are unique among Atayal dialects in having male and female register distinctions in their vocabulary.

Seediq, also known as Sediq, Taroko, is an Atayalic language spoken in the mountains of Northern Taiwan by the Seediq and Taroko people.

Kavalan was formerly spoken in the Northeast coast area of Taiwan by the Kavalan people (噶瑪蘭). It is an East Formosan language of the Austronesian family.

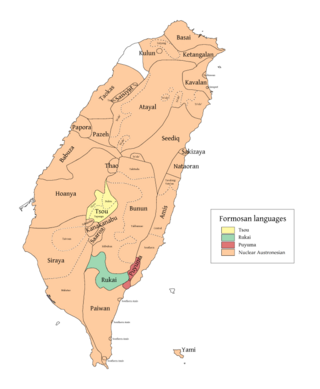

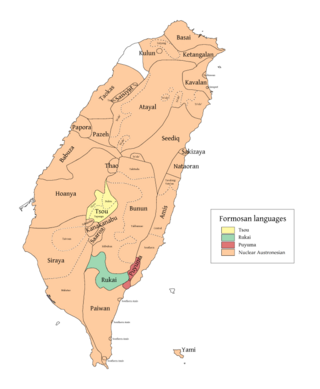

The Puyuma language or Pinuyumayan, is the language of the Puyuma, an indigenous people of Taiwan. It is a divergent Formosan language of the Austronesian family. Most speakers are older adults.

Rukai is a Formosan language spoken by the Rukai people in Taiwan. It is a member of the Austronesian language family. The Rukai language comprises six dialects, which are Budai, Labuan, Maga, Mantauran, Tanan and Tona. The number of speakers of the six Rukai dialects is estimated to be about 10,000. Some of them are monolingual. There are varying degrees of mutual intelligibility among the Rukai dialects. Rukai is notable for its distinct grammatical voice system among the Formosan languages.

Thao, also known as Sao, is the nearly extinct language of the Thao people, an indigenous people of Taiwan from the Sun Moon Lake region in central Taiwan. It is a Formosan language of the Austronesian family; Barawbaw and Shtafari are dialects.

Pazeh and Kaxabu are dialects of an extinct language of the Pazeh and Kaxabu, neighboring Taiwanese indigenous peoples. The language was Formosan, of the Austronesian language family. The last remaining native speaker of the Pazeh dialect died in 2010.

Symmetrical voice, also known as Austronesian alignment, the Philippine-type voice system or the Austronesian focus system, is a typologically unusual kind of morphosyntactic alignment in which "one argument can be marked as having a special relationship to the verb". This special relationship manifests itself as a voice affix on the verb that corresponds to the syntactic role of a noun within the clause, that is either marked for a particular grammatical case or is found in a privileged structural position within the clause or both.

While other word categories in Ilocano are not as diverse in forms, verbs are morphologically complex inflecting chiefly for aspect. Ilocano verbs can also be cast in any one of five foci or triggers. In turn, these foci can inflect for different grammatical moods.

Proto-Austronesian is a proto-language. It is the reconstructed ancestor of the Austronesian languages, one of the world's major language families. Proto-Austronesian is assumed to have begun to diversify c. 4000 BCE – c. 3500 BCE in Taiwan.

Cebuano grammar encompasses the rules that define the Cebuano language, the most widely spoken of all the languages in the Visayan Group of languages, spoken in Cebu, Bohol, Siquijor, part of Leyte island, part of Samar island, Negros Oriental, especially in Dumaguete, and the majority of cities and provinces of Mindanao.

Siraya is a Formosan language spoken until the end of the 19th century by the indigenous Siraya people of Taiwan, derived from Proto-Siraya. Some scholars believe Taivoan and Makatao are two dialects of Siraya, but now more evidence shows that they should be classified as separate languages.

Favorlang is an extinct Formosan language closely related to Babuza.

Matigsalug is a Manobo language of Mindanao in the Philippines. It belongs to the Austronesian language family.

Yami language, also known as Tao language, is a Malayo-Polynesian and Philippine language spoken by the Tao people of Orchid Island, 46 kilometers southeast of Taiwan. It is a member of the Ivatan dialect continuum.