The Austronesian languages are a language family widely spoken throughout Maritime Southeast Asia, parts of Mainland Southeast Asia, Madagascar, the islands of the Pacific Ocean and Taiwan. They are spoken by about 386 million people. This makes it the fifth-largest language family by number of speakers. Major Austronesian languages include Malay, Javanese, Sundanese, Tagalog, Malagasy and Cebuano. According to some estimates, the family contains 1,257 languages, which is the second most of any language family.

TaaTAH, also known as ǃXóõKOH, is a Tuu language notable for its large number of phonemes, perhaps the largest in the world. It is also notable for having perhaps the heaviest functional load of click consonants, with one count finding that 82% of basic vocabulary items started with a click. Most speakers live in Botswana, but a few hundred live in Namibia. The people call themselves ǃXoon or ʼNǀohan, depending on the dialect they speak. The Tuu languages are one of the three traditional language families that make up the Khoisan languages. In 2011, there were around 2,500 speakers of Taa.

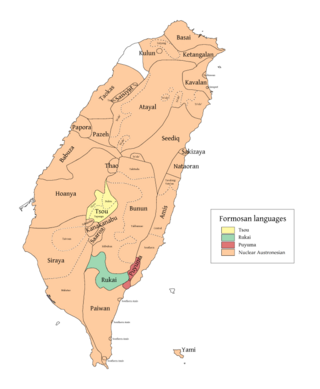

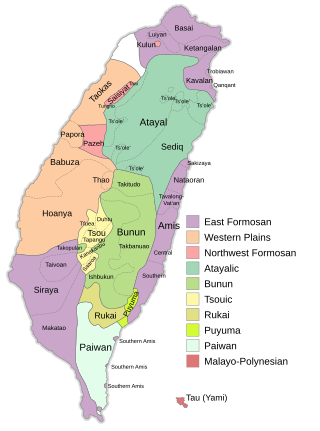

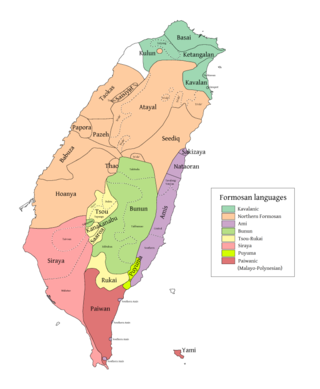

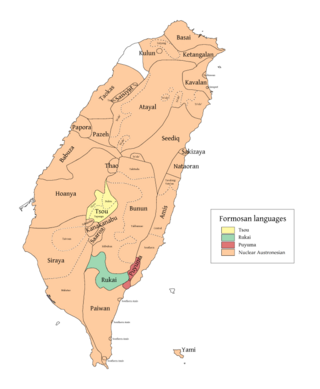

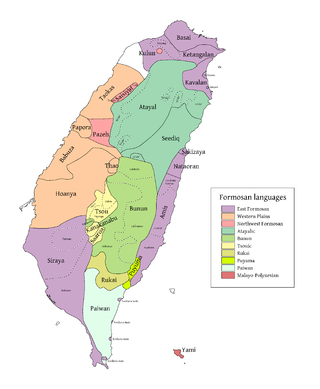

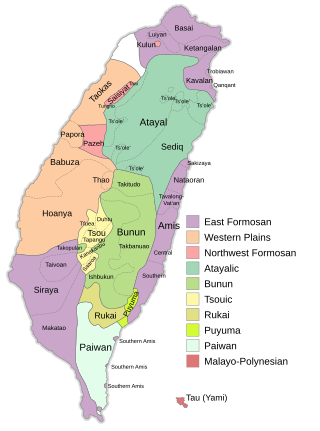

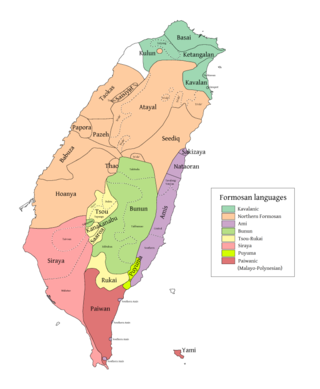

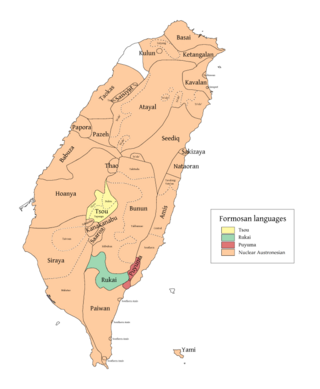

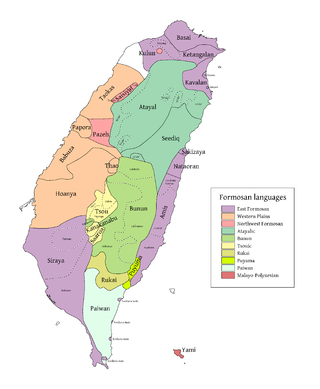

The Formosan languages are a geographic grouping comprising the languages of the indigenous peoples of Taiwan, all of which are Austronesian. They do not form a single subfamily of Austronesian but rather up to nine separate primary subfamilies. The Taiwanese indigenous peoples recognized by the government are about 2.3% of the island's population. However, only 35% speak their ancestral language, due to centuries of language shift. Of the approximately 26 languages of the Taiwanese indigenous peoples, at least ten are extinct, another four are moribund, and all others are to some degree endangered.

Sandawe is a language spoken by about 60,000 Sandawe people in the Dodoma Region of Tanzania. Sandawe's use of click consonants, a rare feature shared with only two other languages of East Africa – Hadza and Dahalo, had been the basis of its classification as a member of the defunct Khoisan family of Southern Africa since Albert Drexel in the 1920s. Recent investigations however suggest that Sandawe may be related to the Khoe family regardless of the validity of Khoisan as a whole. A discussion of Sandawe's linguistic classification can be found in Sands (1998).

The Wariʼ language is the sole remaining vibrant language of the Chapacuran language family of the Brazilian–Bolivian border region of the Amazon. It has about 2,700 speakers, also called Wariʼ, who live along tributaries of the Pacaas Novos river in Western Brazil. The word wariʼ means "we!" in the Wariʼ language and is the term given to the language and tribe by its speakers.

Seediq, also known as Sediq, Taroko, is an Atayalic language spoken in the mountains of Northern Taiwan by the Seediq and Taroko people.

Kavalan was formerly spoken in the Northeast coast area of Taiwan by the Kavalan people (噶瑪蘭). It is an East Formosan language of the Austronesian family.

The Puyuma language or Pinuyumayan, is the language of the Puyuma, an indigenous people of Taiwan. It is a divergent Formosan language of the Austronesian family. Most speakers are older adults.

Rukai is a Formosan language spoken by the Rukai people in Taiwan. It is a member of the Austronesian language family. The Rukai language comprises six dialects, which are Budai, Labuan, Maga, Mantauran, Tanan and Tona. The number of speakers of the six Rukai dialects is estimated to be about 10,000. Some of them are monolingual. There are varying degrees of mutual intelligibility among the Rukai dialects. Rukai is notable for its distinct grammatical voice system among the Formosan languages.

Pazeh and Kaxabu are dialects of an extinct language of the Pazeh and Kaxabu, neighboring Taiwanese indigenous peoples. The language was Formosan, of the Austronesian language family. The last remaining native speaker of the Pazeh dialect died in 2010.

Kanakanavu is a Southern Tsouic language spoken by the Kanakanavu people, an indigenous people of Taiwan. It is a Formosan language of the Austronesian family.

Saaroa or Lhaʼalua is a Southern Tsouic language spoken by the Saaroa (Hla'alua) people, an indigenous people of Taiwan. It is a Formosan language of the Austronesian family.

Kara is an Austronesian language spoken by about 5,000 people in 1998 in the Kavieng District of New Ireland Province, Papua New Guinea.

Proto-Austronesian is a proto-language. It is the reconstructed ancestor of the Austronesian languages, one of the world's major language families. Proto-Austronesian is assumed to have begun to diversify c. 4000 BCE – c. 3500 BCE in Taiwan.

This article is about the sound system of the Navajo language. The phonology of Navajo is intimately connected to its morphology. For example, the entire range of contrastive consonants is found only at the beginning of word stems. In stem-final position and in prefixes, the number of contrasts is drastically reduced. Similarly, vowel contrasts found outside of the stem are significantly neutralized. For details about the morphology of Navajo, see Navajo grammar.

In phonetics, a homorganic consonant is a consonant sound that is articulated in the same place of articulation as another. For example,, and are homorganic consonants of one another since they share the bilabial place of articulation. Consonants that are not articulated in the same place are called heterorganic.

The phonology of Burmese is fairly typical of a Southeast Asian language, involving phonemic tone or register, a contrast between major and minor syllables, and strict limitations on consonant clusters.

This article describes the personal pronoun systems of various Austronesian languages.

The Hawu language is the language of the Savu people of Savu Island in Indonesia and of Raijua Island off the western tip of Savu. Hawu has been referred to by a variety of names such as Havu, Savu, Sabu, Sawu, and is known to outsiders as Savu or Sabu. Hawu belongs to the Malayo-Polynesian branch of the Austronesian language family, and is most closely related to Dhao and the languages of Sumba. Dhao was once considered a dialect of Hawu, but the two languages are not mutually intelligible.

Wamesa is an Austronesian language of Indonesian New Guinea, spoken across the neck of the Doberai Peninsula or Bird's Head. There are currently 5,000–8,000 speakers. While it was historically used as a lingua franca, it is currently considered an under-documented, endangered language. This means that fewer and fewer children have an active command of Wamesa. Instead, Papuan Malay has become increasingly dominant in the area.