In chess, a queen sacrifice is a move that sacrifices a queen, the most powerful piece, in return for some compensation, such as a tactical or positional advantage.

In chess, a queen sacrifice is a move that sacrifices a queen, the most powerful piece, in return for some compensation, such as a tactical or positional advantage.

In his book The Art of Sacrifice in Chess, Rudolf Spielmann distinguishes between real and sham sacrifices. A sham sacrifice leads to a forced and immediate benefit for the sacrificer, usually in the form of a quick checkmate (or perpetual check or stalemate if seeking a draw), or the recouping of the sacrificed material after a forced line . Since any amount of material can be sacrificed as long as checkmate will be achieved, the queen is not above being sacrificed as part of a combination. [1]

Possible reasons for a sham queen sacrifice include:

Despite the terminology "sham", sham queen sacrifices are still often considered brilliancies and are often featured in famous games.

On the other hand, "real" sacrifices, according to Spielmann, are those where the compensation is not immediate, but more positional in nature. Because the queen is the most powerful piece (see chess piece relative value), positional sacrifices of the queen virtually always entail some partial material compensation (for example, sacrificing the queen for a rook and bishop).

An opportunity may arise where a player trades off their queen for other pieces which may together be of equal or greater value than the queen. Bent Larsen remarks that giving up the queen for a rook and two minor pieces is sometimes called a "queen sacrifice", but since a rook plus two minor pieces is more valuable than the queen, he says it should not be considered a sacrifice. [2]

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |  | 8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

A celebrated game by Adolf Anderssen, the Immortal Game, featured a queen sacrifice as part of White's final mating combination. In the diagram position Anderssen gave up his queen with 22.Qf6+! to deflect Black's knight: the game continued 22...Nxf6 23.Be7#. This is an example of a sham queen sacrifice, as the sacrifice resulted in checkmate only one move later. White was able to mate since his minor pieces were clustered around the Black king, while Black's pieces were either undeveloped or trapped in the white camp and so unable to defend.

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |  | 8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

In another celebrated game by Anderssen, the Evergreen Game, Anderssen once again sacrificed his queen for a mating combination, playing 21.Qxd7+!!. The game continued 21...Kxd7 22.Bf5+ Ke8 23.Bd7+ Kf8 24.Bxe7#. The game is another example of a sham queen sacrifice. Although Black is on the verge of checkmating White, his defences around his king are weak, so White was able to mate.

White to move |

Position after 13.h4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

For an example of a "real" (positional) queen sacrifice, Rudolf Spielmann presented this game against Jorgen Moeller in Gothenburg 1920. In the first diagram Black threatens 9...Bg4 winning the queen, since it must not leave the f2-square unguarded under threat of checkmate. But Spielmann played 9.Nd2! allowing Black to win his queen, and after 9...Bg4 10.Nxe4 Bxf3 11.Nxf3 Qh6 12.Nf6+ Kd8 13.h4 the position in the second diagram was reached. White has only a knight and bishop for his queen and pawn, but his minor pieces are very active and the black queen is out of play. White won on move 28. [3]

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |  | 8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

A queen sacrifice can sometimes be used as a resource to draw. Here Hermann Pilnik (White) is defending an endgame three pawns down, but played Qf2!, when Samuel Reshevsky (Black) had nothing better than ...Qxf2 stalemate. [4]

Black to move |

Position after 25...Nxd1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In The Game of the Century, Bobby Fischer uncorked a queen sacrifice to obtain a winning material advantage. In the first diagram, White's king is stuck in the center and Black has control of the open e-file. Fischer ignored the threat to his queen and played 17...Be6!!. The game continued 18.Bxb6 Bxc4+ 19.Kg1 Ne2+ 20.Kf1 Nxd4+ 21.Kg1 Ne2+ 22.Kf1 Nc3+ 23.Kg1 axb6 24.Qb4 Ra4 25.Qxb6 Nxd1 and Black has emerged with a large material and positional advantage. He can threaten back-rank mate to win even more material; his pieces are coordinated and White's rook is trapped in the corner. Black went on to win the game. [5]

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |  | 8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

In the World Chess Championship 2016, Magnus Carlsen defeated Sergey Karjakin in the final tie-break game with the queen sacrifice 50.Qh6+!!. Either way the queen is captured, there is mate on the next move: 50...Kxh6 51.Rh8#, or 50...gxh6 51.Rxf7#. [6]

Zugzwang is a situation found in chess and other turn-based games wherein one player is put at a disadvantage because of their obligation to make a move; a player is said to be "in zugzwang" when any legal move will worsen their position.

The Game of the Century is a chess game that was won by the 13-year-old future world champion Bobby Fischer against Donald Byrne in the Rosenwald Memorial Tournament at the Marshall Chess Club in New York City on October 17, 1956. In Chess Review, Hans Kmoch dubbed it "The Game of the Century" and wrote: "The following game, a stunning masterpiece of combination play performed by a boy of 13 against a formidable opponent, matches the finest on record in the history of chess prodigies."

The Immortal Game was a chess game played in 1851 by Adolf Anderssen and Lionel Kieseritzky. It was played while the London 1851 chess tournament was in progress, an event in which both players participated. The Immortal Game was itself a casual game, however, not played as part of the tournament. Anderssen won the game by allowing a double rook sacrifice, a major loss of material, while also developing a mating attack with his remaining minor pieces. Despite losing the game, Kieseritzky was impressed with Anderssen's performance. Shortly after it was played, Kieseritzky published the game in La Régence, a French chess journal which he helped to edit. In 1855, Ernst Falkbeer published an analysis of the game, describing it for the first time with its namesake "immortal".

The Evergreen Game is a famous chess game won by Adolf Anderssen against Jean Dufresne in 1852.

In chess, a smothered mate is a checkmate delivered by a knight in which the mated king is unable to move because it is completely surrounded by its own pieces.

In chess, a relative value is a standard value conventionally assigned to each piece. Piece valuations have no role in the rules of chess but are useful as an aid to assessing a position.

In chess and other related games, a double check is a check delivered by two pieces simultaneously. In chess notation, it is almost always represented the same way as a single check ("+"), but is sometimes symbolized by "++". This article uses "++" for double check and "#" for checkmate.

In chess, a pure mate is a checkmate position such that the mated king is attacked exactly once, and prevented from moving to any of the adjacent squares in its field for exactly one reason per square. Each of the squares in the mated king's field is attacked or "guarded" by one—and only one—attacking unit, or else a square which is not attacked is occupied by a friendly unit, a unit of the same color as the mated king. Some authors allow that special situations involving double check or pins may also be considered as pure mate.

Anderssen's Opening is a chess opening defined by the opening move:

Handicaps in chess are handicapping variants which enable a weaker player to have a chance of winning against a stronger one. There are a variety of such handicaps, such as material odds, extra moves, extra time on the chess clock, and special conditions. Various permutations of these, such as "pawn and two moves", are also possible.

The Légal Trap or Blackburne Trap is a chess opening trap, characterized by a queen sacrifice followed by checkmate with minor pieces if Black accepts the sacrifice. The trap is named after the French player Sire de Légall. Joseph Henry Blackburne, a British master and one of the world's top five players in the latter part of the 19th century, set the trap on many occasions.

In chess, a sacrifice is a move that gives up a piece with the objective of gaining tactical or positional compensation in other forms. A sacrifice could also be a deliberate exchange of a chess piece of higher value for an opponent's piece of lower value.

In chess, the exchange is the material difference of a rook for a minor piece. Having a rook for a minor piece is generally advantageous, since the rook is usually more valuable. A player who has a rook for a minor piece is said to be up the exchange, and the other player is down the exchange. A player who wins a rook for a minor piece is said to have won the exchange, while the other player has lost the exchange. The opposing captures often happen on consecutive moves, but this is not strictly necessary. Although it is generally detrimental to lose the exchange, one may occasionally find reason to purposely do so; the result is an exchange sacrifice.

In chess, a fortress is an endgame drawing technique in which the side behind in material sets up a zone of protection that the opponent cannot penetrate. This might involve keeping the enemy king out of one's position, or a zone the enemy cannot force one out of. An elementary fortress is a theoretically drawn position with reduced material in which a passive defense will maintain the draw.

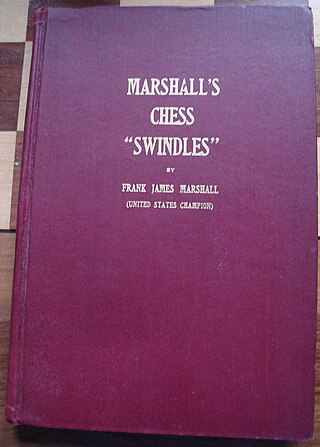

In chess, a swindle is a ruse by which a player in a losing position tricks their opponent and thereby achieves a win or draw instead of the expected loss. It may also refer more generally to obtaining a win or draw from a clearly losing position. I. A. Horowitz and Fred Reinfeld distinguish among "traps", "pitfalls", and "swindles". In their terminology, a "trap" refers to a situation where players go wrong through their own efforts. In a "pitfall", the beneficiary of the pitfall plays an active role, creating a situation where a plausible move by the opponent will turn out badly. A "swindle" is a pitfall adopted by a player who has a clearly lost game. Horowitz and Reinfeld observe that swindles, "though ignored in virtually all chess books", "play an enormously important role in over-the-board chess, and decide the fate of countless games".

In chess, a windmill is a tactic in which a piece repeatedly gains material while simultaneously creating an inescapable series of alternating direct and discovered checks. Because the opponent must attend to check every move, they are unable to prevent their pieces from being captured; thus, windmills can be extremely powerful. A windmill most commonly consists of a rook supported by a bishop.

In chess, several checkmate patterns occur frequently enough to have acquired specific names in chess commentary. By definition, a checkmate pattern is a recognizable/particular/studied arrangements of pieces that delivers checkmate. The diagrams that follow show these checkmates with White checkmating Black.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to chess:

In chess, an economical mate is a checkmate position such that all of the attacker's remaining knights, bishops, rooks and queens contribute to the mating attack. The attacker's king and pawns may also contribute to the mate, but their assistance is not required, nor does it disqualify the position from being an economical mate. Economical mates are of interest to chess problem composers for their aesthetic value. In real gameplay, their occurrence is incidental. Nevertheless, some notable games have concluded with an economical mate such as the Opera game, won by Paul Morphy.