Brain abscess is an abscess within the brain tissue caused by inflammation and collection of infected material coming from local or remote infectious sources. The infection may also be introduced through a skull fracture following a head trauma or surgical procedures. Brain abscess is usually associated with congenital heart disease in young children. It may occur at any age but is most frequent in the third decade of life.

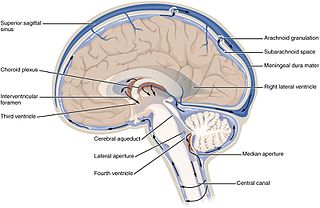

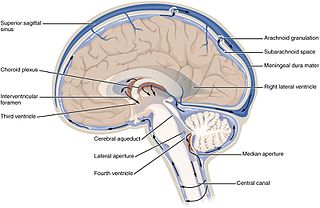

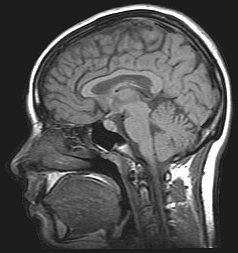

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is a clear, colorless body fluid found within the tissue that surrounds the brain and spinal cord of all vertebrates.

Idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH), previously known as pseudotumor cerebri and benign intracranial hypertension, is a condition characterized by increased intracranial pressure without a detectable cause. The main symptoms are headache, vision problems, ringing in the ears, and shoulder pain. Complications may include vision loss.

Viral meningitis, also known as aseptic meningitis, is a type of meningitis due to a viral infection. It results in inflammation of the meninges. Symptoms commonly include headache, fever, sensitivity to light and neck stiffness.

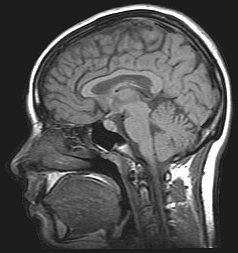

Hydrocephalus is a condition in which an accumulation of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) occurs within the brain. This typically causes increased pressure inside the skull. Older people may have headaches, double vision, poor balance, urinary incontinence, personality changes, or mental impairment. In babies, it may be seen as a rapid increase in head size. Other symptoms may include vomiting, sleepiness, seizures, and downward pointing of the eyes.

Colpocephaly is a cephalic disorder involving the disproportionate enlargement of the occipital horns of the lateral ventricles and is usually diagnosed early after birth due to seizures. It is a nonspecific finding and is associated with multiple neurological syndromes, including agenesis of the corpus callosum, Chiari malformation, lissencephaly, and microcephaly. Although the exact cause of colpocephaly is not known yet, it is commonly believed to occur as a result of neuronal migration disorders during early brain development, intrauterine disturbances, perinatal injuries, and other central nervous system disorders. Individuals with colpocephaly have various degrees of motor disabilities, visual defects, spasticity, and moderate to severe intellectual disability. No specific treatment for colpocephaly exists, but patients may undergo certain treatments to improve their motor function or intellectual disability.

Lumbar puncture (LP), also known as a spinal tap, is a medical procedure in which a needle is inserted into the spinal canal, most commonly to collect cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) for diagnostic testing. The main reason for a lumbar puncture is to help diagnose diseases of the central nervous system, including the brain and spine. Examples of these conditions include meningitis and subarachnoid hemorrhage. It may also be used therapeutically in some conditions. Increased intracranial pressure is a contraindication, due to risk of brain matter being compressed and pushed toward the spine. Sometimes, lumbar puncture cannot be performed safely. It is regarded as a safe procedure, but post-dural-puncture headache is a common side effect if a small atraumatic needle is not used.

Normal-pressure hydrocephalus (NPH), also called malresorptive hydrocephalus, is a form of communicating hydrocephalus in which excess cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) occurs in the ventricles, and with normal or slightly elevated cerebrospinal fluid pressure. As the fluid builds up, it causes the ventricles to enlarge and the pressure inside the head to increase, compressing surrounding brain tissue and leading to neurological complications. The disease presents in a classic triad of symptoms, which are memory impairment, urinary frequency, and balance problems/gait deviations. The disease was first described by Salomón Hakim and Adams in 1965.

A craniotomy is a surgical operation in which a bone flap is temporarily removed from the skull to access the brain. Craniotomies are often critical operations, performed on patients who are suffering from brain lesions, such as tumors, blood clots, removal of foreign bodies such as bullets, or traumatic brain injury (TBI), and can also allow doctors to surgically implant devices, such as deep brain stimulators for the treatment of Parkinson's disease, epilepsy, and cerebellar tremor. The procedure is also used in epilepsy surgery to remove the parts of the brain that are causing epilepsy.

A cerebral shunt is a device permanently implanted inside the head and body to drain excess fluid away from the brain. They are commonly used to treat hydrocephalus, the swelling of the brain due to excess buildup of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). If left unchecked, the excess CSF can lead to an increase in intracranial pressure (ICP), which can cause intracranial hematoma, cerebral edema, crushed brain tissue or herniation. The drainage provided by a shunt can alleviate or prevent these problems in patients with hydrocephalus or related diseases.

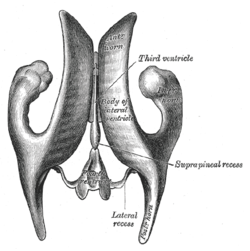

Intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH), also known as intraventricular bleeding, is a bleeding into the brain's ventricular system, where the cerebrospinal fluid is produced and circulates through towards the subarachnoid space. It can result from physical trauma or from hemorrhagic stroke.

An external ventricular drain (EVD), also known as a ventriculostomy or extraventricular drain, is a device used in neurosurgery to treat hydrocephalus and relieve elevated intracranial pressure when the normal flow of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) inside the brain is obstructed. An EVD is a flexible plastic catheter placed by a neurosurgeon or neurointensivist and managed by intensive care unit (ICU) physicians and nurses. The purpose of external ventricular drainage is to divert fluid from the ventricles of the brain and allow for monitoring of intracranial pressure. An EVD must be placed in a center with full neurosurgical capabilities, because immediate neurosurgical intervention can be needed if a complication of EVD placement, such as bleeding, is encountered.

Mollaret's meningitis is a recurrent or chronic inflammation of the protective membranes covering the brain and spinal cord, known collectively as the meninges. Since Mollaret's meningitis is a recurrent, benign (non-cancerous), aseptic meningitis, it is also referred to as benign recurrent lymphocytic meningitis. It was named for Pierre Mollaret, the French neurologist who first described it in 1944.

Meningitis is acute or chronic inflammation of the protective membranes covering the brain and spinal cord, collectively called the meninges. The most common symptoms are fever, headache, and neck stiffness. Other symptoms include confusion or altered consciousness, nausea, vomiting, and an inability to tolerate light or loud noises. Young children often exhibit only nonspecific symptoms, such as irritability, drowsiness, or poor feeding. A non-blanching rash may also be present.

A cerebrospinal fluid leak is a medical condition where the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) surrounding the brain or spinal cord leaks out of one or more holes or tears in the dura mater. A cerebrospinal fluid leak can be either cranial or spinal, and these are two different disorders. A spinal CSF leak can be caused by one or more meningeal diverticula or CSF-venous fistulas not associated with an epidural leak.

Bobble-head doll syndrome is a rare neurological movement disorder in which patients, usually children around age 3, begin to bob their head and shoulders forward and back, or sometimes side-to-side, involuntarily, in a manner reminiscent of a bobblehead doll. The syndrome is related to cystic lesions and swelling of the third ventricle in the brain. Symptoms of bobble-head doll syndrome are diverse but can be grouped into two categories: physical and neurological. The most common form of treatment is surgical implanting of a shunt to relieve the swelling of the brain.

Citrobacter koseri, formerly known as Citrobacter diversus, is a Gram-negative, non-spore-forming bacillus. It is a facultative anaerobe capable of aerobic respiration. It is motile via peritrichous flagella. It is a member of the family of Enterobacteriaceae. The members of this family are the part of the normal flora and commonly found in the digestive tracts of humans and animals. C. koseri may act as an opportunistic pathogen in individuals who are immunocompromised.

Neonatal meningitis is a serious medical condition in infants that is rapidly fatal if untreated. Meningitis is an inflammation of the meninges, the protective membranes of the central nervous system, is more common in the neonatal period than any other time in life, and is an important cause of morbidity and mortality globally. Mortality is roughly half in developing countries and ranges from 8%-12.5% in developed countries.

Aqueductal stenosis is a narrowing of the aqueduct of Sylvius which blocks the flow of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) in the ventricular system. Blockage of the aqueduct can lead to hydrocephalus, specifically as a common cause of congenital and/or obstructive hydrocephalus.

Intracerebroventricular injection is a route of administration for drugs via injection into the cerebral ventricles so that it reaches the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). This route of administration is often used to bypass the blood-brain barrier because it can prevent important medications from reaching the central nervous system. This injection method is widely used in diseased mice models to study the effect of drugs, plasmid DNA, and viral vectors on the central nervous system. In humans, ICV injection can be used for the administration of drugs for various reasons. Examples include the treatment of Spinal Muscular Atrophy (SMA), the administration of chemotherapy in gliomas, and the administration of drugs for long-term pain management. ICV injection is also used in the creation of diseased animal models specifically to model neurological disorders.