Human papillomavirus infection is caused by a DNA virus from the Papillomaviridae family. Many HPV infections cause no symptoms and 90% resolve spontaneously within two years. In some cases, an HPV infection persists and results in either warts or precancerous lesions. These lesions, depending on the site affected, increase the risk of cancer of the cervix, vulva, vagina, penis, anus, mouth, tonsils, or throat. Nearly all cervical cancer is due to HPV, and two strains – HPV16 and HPV18 – account for 70% of all cases. HPV16 is responsible for almost 90% of HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancers. Between 60% and 90% of the other cancers listed above are also linked to HPV. HPV6 and HPV11 are common causes of genital warts and laryngeal papillomatosis.

Genital warts are a sexually transmitted infection caused by certain types of human papillomavirus (HPV). They may be flat or project out from the surface of the skin, and their color may vary; brownish, white, pale yellow, pinkish-red, or gray. There may be a few individual warts or several, either in a cluster or merged together to look cauliflower-shaped. They can be itchy and feel burning. Usually they cause few symptoms, but can occasionally be painful. Typically they appear one to eight months following exposure. Warts are the most easily recognized symptom of genital HPV infection.

A plantar wart is a wart occurring on the bottom of the foot or toes. Its color is typically similar to that of the skin. Small black dots often occur on the surface. One or more may occur in an area. They may result in pain with pressure such that walking is difficult.

Penile cancer, or penile carcinoma, is a cancer that develops in the skin or tissues of the penis. Symptoms may include abnormal growth, an ulcer or sore on the skin of the penis, and bleeding or foul smelling discharge.

Actinic keratosis (AK), sometimes called solar keratosis or senile keratosis, is a pre-cancerous area of thick, scaly, or crusty skin. Actinic keratosis is a disorder of epidermal keratinocytes that is induced by ultraviolet (UV) light exposure. These growths are more common in fair-skinned people and those who are frequently in the sun. They are believed to form when skin gets damaged by UV radiation from the sun or indoor tanning beds, usually over the course of decades. Given their pre-cancerous nature, if left untreated, they may turn into a type of skin cancer called squamous cell carcinoma. Untreated lesions have up to a 20% risk of progression to squamous cell carcinoma, so treatment by a dermatologist is recommended.

A papilloma is a benign epithelial tumor growing exophytically in nipple-like and often finger-like fronds. In this context, papilla refers to the projection created by the tumor, not a tumor on an already existing papilla.

Pearly penile papules are benign, small bumps or spots on the human penis. They vary in size from 1–4 mm, are pearly or flesh-colored, smooth and dome-topped or filiform, and appear in one or, several rows around the corona, the ridge of the head of the penis and sometimes on the penile shaft. They are painless, non-cancerous and not harmful. The medical condition of having such papules is called hirsutoid papillomatosis or hirsuties papillaris coronae glandis.

Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccines are vaccines that prevent infection by certain types of human papillomavirus (HPV). Available HPV vaccines protect against either two, four, or nine types of HPV. All HPV vaccines protect against at least HPV types 16 and 18, which cause the greatest risk of cervical cancer. It is estimated that HPV vaccines may prevent 70% of cervical cancer, 80% of anal cancer, 60% of vaginal cancer, 40% of vulvar cancer, and show more than 90% efficacy in preventing HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancers. They additionally prevent some genital warts, with the quadrivalent and nonavalent vaccines that protect against HPV types HPV-6 and HPV-11 providing greater protection.

A skin infection is an infection of the skin in humans and other animals, that can also affect the associated soft tissues such as loose connective tissue and mucous membranes. They comprise a category of infections termed skin and skin structure infections (SSSIs), or skin and soft tissue infections (SSTIs), and acute bacterial SSSIs (ABSSSIs). They are distinguished from dermatitis, although skin infections can result in skin inflammation.

Duct tape occlusion therapy (DTOT) is a method of treating warts by covering them with duct tape for prolonged periods.

Gardasil is an HPV vaccine for use in the prevention of certain strains of human papillomavirus (HPV). It was developed by Merck & Co. High-risk human papilloma virus (hr-HPV) genital infection is the most common sexually transmitted infection among women. The HPV strains that Gardasil protects against are sexually transmitted, specifically HPV types 6, 11, 16 and 18. HPV types 16 and 18 cause an estimated 70% of cervical cancers, and are responsible for most HPV-induced anal, vulvar, vaginal, and penile cancer cases. HPV types 6 and 11 cause an estimated 90% of genital warts cases. HPV type 16 is responsible for almost 90% of HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancers, and the prevalence is higher in males than females. Though Gardasil does not treat existing infection, vaccination is still recommended for HPV-positive individuals, as it may protect against one or more different strains of the disease.

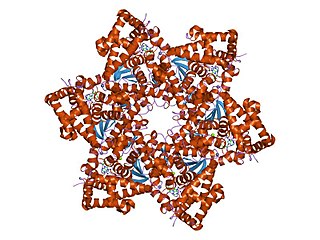

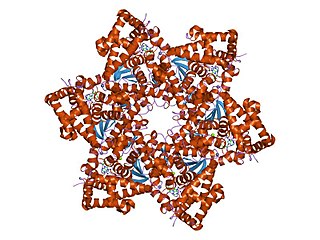

Bovine papillomaviruses (BPV) are a paraphyletic group of DNA viruses of the subfamily Firstpapillomavirinae of Papillomaviridae that are common in cattle. All BPVs have a circular double-stranded DNA genome. Infection causes warts of the skin and alimentary tract, and more rarely cancers of the alimentary tract and urinary bladder. They are also thought to cause the skin tumour equine sarcoid in horses and donkeys.

Cervarix is a vaccine against certain types of cancer-causing human papillomavirus (HPV).

Vulvar cancer is a cancer of the vulva, the outer portion of the female genitals. It most commonly affects the labia majora. Less often, the labia minora, clitoris, or Bartholin's glands are affected. Symptoms include a lump, itchiness, changes in the skin, or bleeding from the vulva.

Epidermodysplasia verruciformis (EV) is a skin condition characterised by warty skin lesions. It results from an abnormal susceptibility to HPV infection (HPV) and is associated with a high lifetime risk of squamous cell carcinomas in skin. It generally presents with scaly spots and small bumps particularly on the hands, feet, face and neck; typically beginning in childhood or in a young adult. The bumps tend to be flat, grow in number and then merge to form plaques. On the trunk, it typically appears like pityriasis versicolor; lesions there being slightly scaly and tan, brown, red or looking pale. On the elbows, it may appear like psoriasis. On the forehead, neck and trunk, the lesions may appear like seborrheic keratosis.

Margaret Anne Stanley, OBE FMedSc, is a British virologist and epithelial biologist. She attended the Universities of London, Bristol, and Adelaide. As of 2018, she is an Emeritus Professor of Epithelial Biology in the Department of Pathology at the University of Cambridge and a Fellow of the Academy of Medical Sciences. She is also an Honorary Fellow of the UK Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists and an honorary fellow of Christ's College, Cambridge. Stanley is a research scientist in virology focusing on the human papillomavirus (HPV). Her research work has led to new scientific findings on HPV. Additionally, she uses her expertise on HPV to serve on multiple advisory committees and journal editorial boards.

A squamous cell papilloma is a generally benign papilloma that arises from the stratified squamous epithelium of the skin, lip, oral cavity, tongue, pharynx, larynx, esophagus, cervix, vagina or anal canal. Squamous cell papillomas are typically associated with human papillomavirus (HPV) while sometimes the cause is unknown.

HspE7 is an investigational therapeutic vaccine candidate being developed by Nventa Biopharmaceuticals for the treatment of precancerous and cancerous lesions caused by the human papillomavirus (HPV). HspE7 uses recombinant DNA technology to covalently fuse a heat shock protein (Hsp) to a target antigen, thereby stimulating cellular immune system responses to specific diseases. HspE7 is a patented construct consisting of the HPV Type 16 E7 protein and heat shock protein 65 (Hsp65) and is currently the only candidate using Hsp technology to target the over 20 million Americans already infected with HPV.

Cervical cancer screening is a medical screening test designed to identify risk of cervical cancer. Cervical screening may involve looking for viral DNA, and/or to identify abnormal, potentially precancerous cells within the cervix as well as cells that have progressed to early stages of cervical cancer. One goal of cervical screening is to allow for intervention and treatment so abnormal lesions can be removed prior to progression to cancer. An additional goal is to decrease mortality from cervical cancer by identifying cancerous lesions in their early stages and providing treatment prior to progression to more invasive disease.

Human papillomavirus (HPV)-associated oropharyngeal cancer awareness and prevention is a vital concept from a public and community health perspective.