Glycolysis is the metabolic pathway that converts glucose into pyruvate and, in most organisms, occurs in the liquid part of cells. The free energy released in this process is used to form the high-energy molecules adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH). Glycolysis is a sequence of ten reactions catalyzed by enzymes.

Hypoxia is a condition in which the body or a region of the body is deprived of adequate oxygen supply at the tissue level. Hypoxia may be classified as either generalized, affecting the whole body, or local, affecting a region of the body. Although hypoxia is often a pathological condition, variations in arterial oxygen concentrations can be part of the normal physiology, for example, during strenuous physical exercise.

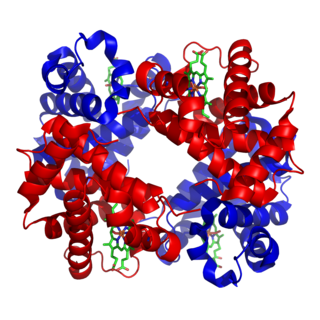

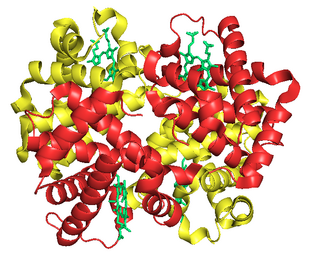

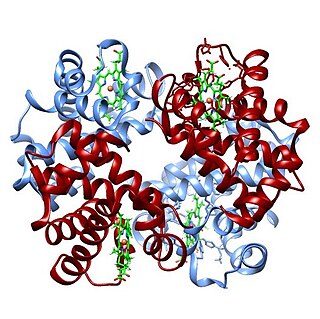

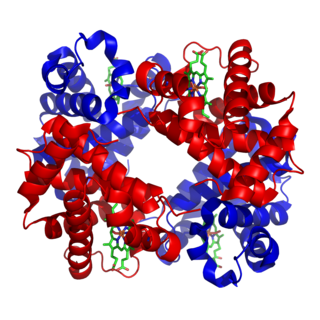

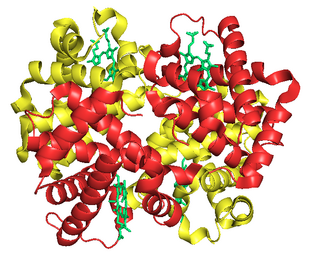

Hemoglobin is a protein containing iron that facilitates the transport of oxygen in red blood cells. Almost all vertebrates contain hemoglobin, with the exception of the fish family Channichthyidae. Hemoglobin in the blood carries oxygen from the respiratory organs to the other tissues of the body, where it releases the oxygen to enable aerobic respiration which powers the animal's metabolism. A healthy human has 12 to 20 grams of hemoglobin in every 100 mL of blood. Hemoglobin is a metalloprotein, a chromoprotein, and globulin.

Tumor hypoxia is the situation where tumor cells have been deprived of oxygen. As a tumor grows, it rapidly outgrows its blood supply, leaving portions of the tumor with regions where the oxygen concentration is significantly lower than in healthy tissues. Hypoxic microenvironments in solid tumors are a result of available oxygen being consumed within 70 to 150 μm of tumor vasculature by rapidly proliferating tumor cells thus limiting the amount of oxygen available to diffuse further into the tumor tissue. In order to support continuous growth and proliferation in challenging hypoxic environments, cancer cells are found to alter their metabolism. Furthermore, hypoxia is known to change cell behavior and is associated with extracellular matrix remodeling and increased migratory and metastatic behavior.

Fetal hemoglobin, or foetal haemoglobin is the main oxygen carrier protein in the human fetus. Hemoglobin F is found in fetal red blood cells, and is involved in transporting oxygen from the mother's bloodstream to organs and tissues in the fetus. It is produced at around 6 weeks of pregnancy and the levels remain high after birth until the baby is roughly 2–4 months old. Hemoglobin F has a different composition than adult forms of hemoglobin, allowing it to bind oxygen more strongly; this in turn enables the developing fetus to retrieve oxygen from the mother's bloodstream, which occurs through the placenta found in the mother's uterus.

The Bohr effect is a phenomenon first described in 1904 by the Danish physiologist Christian Bohr. Hemoglobin's oxygen binding affinity (see oxygen–haemoglobin dissociation curve) is inversely related both to acidity and to the concentration of carbon dioxide. That is, the Bohr effect refers to the shift in the oxygen dissociation curve caused by changes in the concentration of carbon dioxide or the pH of the environment. Since carbon dioxide reacts with water to form carbonic acid, an increase in CO2 results in a decrease in blood pH, resulting in hemoglobin proteins releasing their load of oxygen. Conversely, a decrease in carbon dioxide provokes an increase in pH, which results in hemoglobin picking up more oxygen.

Carboxyhemoglobin is a stable complex of carbon monoxide and hemoglobin (Hb) that forms in red blood cells upon contact with carbon monoxide. Carboxyhemoglobin is often mistaken for the compound formed by the combination of carbon dioxide (carboxyl) and hemoglobin, which is actually carbaminohemoglobin. Carboxyhemoglobin terminology emerged when carbon monoxide was known by its historic name, "carbonic oxide", and evolved through Germanic and British English etymological influences; the preferred IUPAC nomenclature is carbonylhemoglobin.

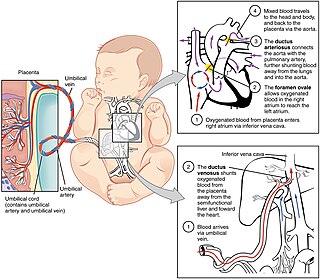

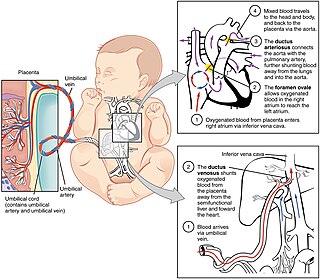

In humans, the circulatory system is different before and after birth. The fetal circulation is composed of the placenta, umbilical blood vessels encapsulated by the umbilical cord, heart and systemic blood vessels. A major difference between the fetal circulation and postnatal circulation is that the lungs are not used during the fetal stage resulting in the presence of shunts to move oxygenated blood and nutrients from the placenta to the fetal tissue. At birth, the start of breathing and the severance of the umbilical cord prompt various changes that quickly transform fetal circulation into postnatal circulation.

1,3-Bisphosphoglyceric acid (1,3-Bisphosphoglycerate or 1,3BPG) is a 3-carbon organic molecule present in most, if not all, living organisms. It primarily exists as a metabolic intermediate in both glycolysis during respiration and the Calvin cycle during photosynthesis. 1,3BPG is a transitional stage between glycerate 3-phosphate and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate during the fixation/reduction of CO2. 1,3BPG is also a precursor to 2,3-bisphosphoglycerate which in turn is a reaction intermediate in the glycolytic pathway.

The oxygen–hemoglobin dissociation curve, also called the oxyhemoglobin dissociation curve or oxygen dissociation curve (ODC), is a curve that plots the proportion of hemoglobin in its saturated (oxygen-laden) form on the vertical axis against the prevailing oxygen tension on the horizontal axis. This curve is an important tool for understanding how our blood carries and releases oxygen. Specifically, the oxyhemoglobin dissociation curve relates oxygen saturation (SO2) and partial pressure of oxygen in the blood (PO2), and is determined by what is called "hemoglobin affinity for oxygen"; that is, how readily hemoglobin acquires and releases oxygen molecules into the fluid that surrounds it.

The Haldane effect is a property of hemoglobin first described by John Scott Haldane, within which oxygenation of blood in the lungs displaces carbon dioxide from hemoglobin, increasing the removal of carbon dioxide. Consequently, oxygenated blood has a reduced affinity for carbon dioxide. Thus, the Haldane effect describes the ability of hemoglobin to carry increased amounts of carbon dioxide (CO2) in the deoxygenated state as opposed to the oxygenated state. Vice versa, it is true that a high concentration of CO2 facilitates dissociation of oxyhemoglobin, though this is the result of two distinct processes (Bohr effect and Margaria-Green effect) and should be distinguished from Haldane effect.

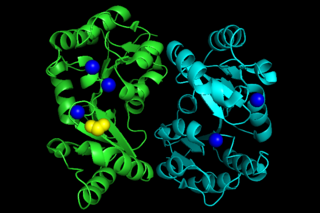

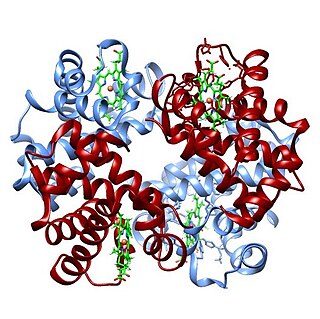

Phosphoglycerate kinase is an enzyme that catalyzes the reversible transfer of a phosphate group from 1,3-bisphosphoglycerate (1,3-BPG) to ADP producing 3-phosphoglycerate (3-PG) and ATP :

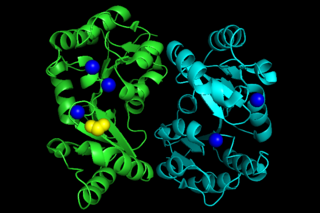

Bisphosphoglycerate mutase is an enzyme expressed in erythrocytes and placental cells. It is responsible for the catalytic synthesis of 2,3-Bisphosphoglycerate (2,3-BPG) from 1,3-bisphosphoglycerate. BPGM also has a mutase and a phosphatase function, but these are much less active, in contrast to its glycolytic cousin, phosphoglycerate mutase (PGM), which favors these two functions, but can also catalyze the synthesis of 2,3-BPG to a lesser extent.

Phosphoglycerate mutase (PGM) is any enzyme that catalyzes step 8 of glycolysis - the internal transfer of a phosphate group from C-3 to C-2 which results in the conversion of 3-phosphoglycerate (3PG) to 2-phosphoglycerate (2PG) through a 2,3-bisphosphoglycerate intermediate. These enzymes are categorized into the two distinct classes of either cofactor-dependent (dPGM) or cofactor-independent (iPGM). The dPGM enzyme is composed of approximately 250 amino acids and is found in all vertebrates as well as in some invertebrates, fungi, and bacteria. The iPGM class is found in all plants and algae as well as in some invertebrate, fungi, and Gram-positive bacteria. This class of PGM enzyme shares the same superfamily as alkaline phosphatase.

Carbamino refers to an adduct generated by the addition of carbon dioxide to the free amino group of an amino acid or a protein, such as hemoglobin forming carbaminohemoglobin.

Phosphoglycolate phosphatase(EC 3.1.3.18; systematic name 2-phosphoglycolate phosphohydrolase), also commonly referred to as phosphoglycolate hydrolase, 2-phosphoglycolate phosphatase, P-glycolate phosphatase, and phosphoglycollate phosphatase, is an enzyme responsible for catalyzing the conversion of 2-phosphoglycolate into glycolate and phosphate:

Oxygen saturation is the fraction of oxygen-saturated haemoglobin relative to total haemoglobin in the blood. The human body requires and regulates a very precise and specific balance of oxygen in the blood. Normal arterial blood oxygen saturation levels in humans are 96–100 percent. If the level is below 90 percent, it is considered low and called hypoxemia. Arterial blood oxygen levels below 80 percent may compromise organ function, such as the brain and heart, and should be promptly addressed. Continued low oxygen levels may lead to respiratory or cardiac arrest. Oxygen therapy may be used to assist in raising blood oxygen levels. Oxygenation occurs when oxygen molecules enter the tissues of the body. For example, blood is oxygenated in the lungs, where oxygen molecules travel from the air and into the blood. Oxygenation is commonly used to refer to medical oxygen saturation.

The Root effect is a physiological phenomenon that occurs in fish hemoglobin, named after its discoverer R. W. Root. It is the phenomenon where an increased proton or carbon dioxide concentration (lower pH) lowers hemoglobin's affinity and carrying capacity for oxygen. The Root effect is to be distinguished from the Bohr effect where only the affinity to oxygen is reduced. Hemoglobins showing the Root effect show a loss of cooperativity at low pH. This results in the Hb-O2 dissociation curve being shifted downward and not just to the right. At low pH, hemoglobins showing the Root effect don't become fully oxygenated even at oxygen tensions up to 20kPa. This effect allows hemoglobin in fish with swim bladders to unload oxygen into the swim bladder against a high oxygen gradient. The effect is also noted in the choroid rete, the network of blood vessels which carries oxygen to the retina. In the absence of the Root effect, retia will result in the diffusion of some oxygen directly from the arterial blood to the venous blood, making such systems less effective for the concentration of oxygen. It has also been hypothesized that the loss of affinity is used to provide more oxygen to red muscle during acidotic stress.

Fish are exposed to large oxygen fluctuations in their aquatic environment since the inherent properties of water can result in marked spatial and temporal differences in the concentration of oxygen. Fish respond to hypoxia with varied behavioral, physiological, and cellular responses to maintain homeostasis and organism function in an oxygen-depleted environment. The biggest challenge fish face when exposed to low oxygen conditions is maintaining metabolic energy balance, as 95% of the oxygen consumed by fish is used for ATP production releasing the chemical energy of nutrients through the mitochondrial electron transport chain. Therefore, hypoxia survival requires a coordinated response to secure more oxygen from the depleted environment and counteract the metabolic consequences of decreased ATP production at the mitochondria.

In biochemistry, the Luebering–Rapoport pathway is a metabolic pathway in mature erythrocytes involving the formation of 2,3-bisphosphoglycerate (2,3-BPG), which regulates oxygen release from hemoglobin and delivery to tissues. 2,3-BPG, the reaction product of the Luebering–Rapoport pathway was first described and isolated in 1925 by the Austrian biochemist Samuel Mitja Rapoport and his technical assistant Jane Luebering.