The Space Shuttle is a retired, partially reusable low Earth orbital spacecraft system operated from 1981 to 2011 by the U.S. National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) as part of the Space Shuttle program. Its official program name was Space Transportation System (STS), taken from a 1969 plan for a system of reusable spacecraft where it was the only item funded for development.

Space Shuttle Enterprise was the first orbiter of the Space Shuttle system. Rolled out on September 17, 1976, it was built for NASA as part of the Space Shuttle program to perform atmospheric test flights after being launched from a modified Boeing 747. It was constructed without engines or a functional heat shield. As a result, it was not capable of spaceflight.

The Space Shuttle program was the fourth human spaceflight program carried out by the U.S. National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), which accomplished routine transportation for Earth-to-orbit crew and cargo from 1981 to 2011. Its official name, Space Transportation System (STS), was taken from a 1969 plan for a system of reusable spacecraft of which it was the only item funded for development. It flew 135 missions and carried 355 astronauts from 16 countries, many on multiple trips.

STS-2 was the second Space Shuttle mission conducted by NASA, and the second flight of the orbiter Columbia. The mission, crewed by Joe H. Engle and Richard H. Truly, launched on November 12, 1981, and landed two days later on November 14, 1981. STS-2 marked the first time that a crewed, reusable orbital vehicle returned to space. This mission tested the Shuttle Imaging Radar (SIR) as part of the OSTA-1 payload, along with a wide range of other experiments including the Shuttle robotic arm, commonly known as Canadarm. Other experiments or tests included Shuttle Multispectral Infrared Radiometer, Feature Identification and Location Experiment, Measurement of Air Pollution from Satellites, Ocean Color Experiment, Night/Day optical Survey of Lightning, Heflex Bioengineering Test, and Aerodynamic Coefficient Identification Package (ACIP). One of the feats accomplished was various tests on the Orbital Maneuvring System (OMS) including starting and restarting the engines while in orbit and various adjustments to its orbit. The OMS tests also helped adjust the Shuttle's orbit for use of the radar. During the mission, President Reagan called the crew of STS-2 from Mission Control Center in Houston.

STS-3 was NASA's third Space Shuttle mission, and was the third mission for the Space Shuttle Columbia. It launched on March 22, 1982, and landed eight days later on March 30, 1982. The mission, crewed by Jack R. Lousma and C. Gordon Fullerton, involved extensive orbital endurance testing of the Columbia itself, as well as numerous scientific experiments. STS-3 was the first shuttle launch with an unpainted external tank, and the only mission to land at the White Sands Space Harbor near Alamogordo, New Mexico. The orbiter was forced to land at White Sands due to flooding at its originally planned landing site, Edwards Air Force Base.

STS-4 was the fourth NASA Space Shuttle mission, and also the fourth for Space Shuttle Columbia. Crewed by Ken Mattingly and Henry Hartsfield, the mission launched on June 27, 1982, and landed a week later on July 4, 1982. Due to parachute malfunctions, the SRBs were not recovered.

Robert Laurel Crippen is an American retired naval officer and aviator, test pilot, aerospace engineer, and retired astronaut. He traveled into space four times: as pilot of STS-1 in April 1981, the first Space Shuttle mission; and as commander of STS-7 in June 1983, STS-41-C in April 1984, and STS-41-G in October 1984. He was also a part of the Manned Orbiting Laboratory (MOL), Skylab Medical Experiment Altitude Test (SMEAT), ASTP support crew member, and the Approach and Landing Tests (ALT) for the Space Shuttle.

Joe Henry Engle is an American pilot, aeronautical engineer and former NASA astronaut. He was the commander of two Space Shuttle missions including STS-2 in 1981, the program's second orbital flight. He also flew two flights in the Shuttle program's 1977 Approach and Landing Tests. Engle is one of twelve pilots who flew the North American X-15, an experimental spaceplane jointly operated by the Air Force and NASA, and the last surviving test pilot of the aircraft. After Richard H. Truly died in 2024, Engle is now the last surviving crew member of STS-2.

Charles Gordon Fullerton was a United States Air Force colonel, a USAF and NASA astronaut, and a research pilot at NASA's Dryden Flight Research Facility, Edwards, California. His assignments included a variety of flight research and support activities piloting NASA's B-52 launch aircraft, the Boeing 747 Shuttle Carrier Aircraft (SCA), and other multi-engine and high performance aircraft.

Vance DeVoe Brand is an American naval officer, aviator, aeronautical engineer, test pilot, and NASA astronaut. He served as command module pilot during the first U.S.-Soviet joint spaceflight in 1975, and as commander of three Space Shuttle missions.

Robert Franklyn "Bob" Overmyer was an American test pilot, naval aviator, aeronautical engineer, physicist, United States Marine Corps officer, and USAF/NASA astronaut. Overmyer was selected by the Air Force as an astronaut for its Manned Orbiting Laboratory in 1966. Upon cancellation of the program in 1969, he became a NASA astronaut and served support crew duties for the Apollo program, Skylab program, and Apollo-Soyuz Test Project. In 1976, he was assigned to the Space Shuttle program and flew as pilot on STS-5 in 1982 and as commander on STS-51-B in 1985. He was selected as a lead investigator into the Space Shuttle Challenger disaster in 1986, retiring from NASA that same year. A decade later, Overmyer died while testing the Cirrus VK-30 homebuilt aircraft.

The Shuttle Carrier Aircraft (SCA) are two retired extensively modified Boeing 747 airliners that NASA used to transport Space Shuttle orbiters. One (N905NA) is a 747-100 model, while the other (N911NA) is a short-range 747-100SR.

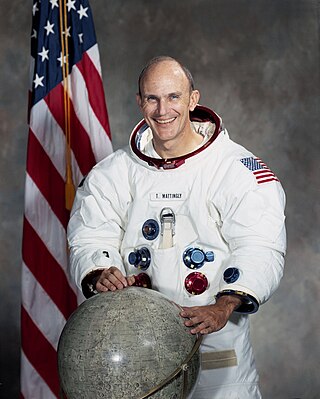

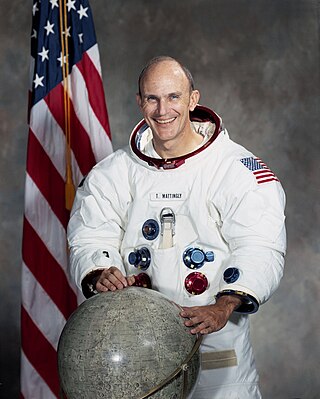

Thomas Kenneth Mattingly II was an American aviator, aeronautical engineer, test pilot, rear admiral in the United States Navy, and astronaut who flew on Apollo 16 and Space Shuttle STS-4 and STS-51-C missions.

A boilerplate spacecraft, also known as a mass simulator, is a nonfunctional craft or payload that is used to test various configurations and basic size, load, and handling characteristics of rocket launch vehicles. It is far less expensive to build multiple, full-scale, non-functional boilerplate spacecraft than it is to develop the full system. In this way, boilerplate spacecraft allow components and aspects of cutting-edge aerospace projects to be tested while detailed contracts for the final project are being negotiated. These tests may be used to develop procedures for mating a spacecraft to its launch vehicle, emergency access and egress, maintenance support activities, and various transportation processes.

Fitzhugh L. "Fitz" Fulton, Jr., , was a civilian research pilot at NASA's Dryden Flight Research Center, Edwards, California, from August 1, 1966, until July 3, 1986, following 23 years of distinguished service as a pilot in the U.S. Air Force.

The Space Shuttle orbiter is the spaceplane component of the Space Shuttle, a partially reusable orbital spacecraft system that was part of the discontinued Space Shuttle program. Operated from 1977 to 2011 by NASA, the U.S. space agency, this vehicle could carry astronauts and payloads into low Earth orbit, perform in-space operations, then re-enter the atmosphere and land as a glider, returning its crew and any on-board payload to the Earth.

A Mate-Demate Device (MDD) is a specialized crane designed to lift a Space Shuttle orbiter onto and off the back of a Shuttle Carrier Aircraft. Four Mate-Demate Devices were built.