A glacier is a persistent body of dense ice that is constantly moving under its own weight. A glacier forms where the accumulation of snow exceeds its ablation over many years, often centuries. It acquires distinguishing features, such as crevasses and seracs, as it slowly flows and deforms under stresses induced by its weight. As it moves, it abrades rock and debris from its substrate to create landforms such as cirques, moraines, or fjords. Although a glacier may flow into a body of water, it forms only on land and is distinct from the much thinner sea ice and lake ice that form on the surface of bodies of water.

Ice is water that is frozen into a solid state, typically forming at or below temperatures of 0 °C, 32 °F, or 273.15 K. As a naturally occurring crystalline inorganic solid with an ordered structure, ice is considered to be a mineral. Depending on the presence of impurities such as particles of soil or bubbles of air, it can appear transparent or a more or less opaque bluish-white color.

An iceberg is a piece of freshwater ice more than 15 m long that has broken off a glacier or an ice shelf and is floating freely in open water. Smaller chunks of floating glacially derived ice are called "growlers" or "bergy bits". Much of an iceberg is below the water's surface, which led to the expression "tip of the iceberg" to illustrate a small part of a larger unseen issue. Icebergs are considered a serious maritime hazard.

The Ross Ice Shelf is the largest ice shelf of Antarctica. It is several hundred metres thick. The nearly vertical ice front to the open sea is more than 600 kilometres (370 mi) long, and between 15 and 50 metres high above the water surface. Ninety percent of the floating ice, however, is below the water surface.

Sea ice arises as seawater freezes. Because ice is less dense than water, it floats on the ocean's surface. Sea ice covers about 7% of the Earth's surface and about 12% of the world's oceans. Much of the world's sea ice is enclosed within the polar ice packs in the Earth's polar regions: the Arctic ice pack of the Arctic Ocean and the Antarctic ice pack of the Southern Ocean. Polar packs undergo a significant yearly cycling in surface extent, a natural process upon which depends the Arctic ecology, including the ocean's ecosystems. Due to the action of winds, currents and temperature fluctuations, sea ice is very dynamic, leading to a wide variety of ice types and features. Sea ice may be contrasted with icebergs, which are chunks of ice shelves or glaciers that calve into the ocean. Depending on location, sea ice expanses may also incorporate icebergs.

An ice shelf is a large platform of glacial ice floating on the ocean, fed by one or multiple tributary glaciers. Ice shelves form along coastlines where the ice thickness is insufficient to displace the more dense surrounding ocean water. The boundary between the ice shelf (floating) and grounded ice is referred to as the grounding line; the boundary between the ice shelf and the open ocean is the ice front or calving front.

An ice core is a core sample that is typically removed from an ice sheet or a high mountain glacier. Since the ice forms from the incremental buildup of annual layers of snow, lower layers are older than upper ones, and an ice core contains ice formed over a range of years. Cores are drilled with hand augers or powered drills; they can reach depths of over two miles (3.2 km), and contain ice up to 800,000 years old.

The Filchner–Ronne Ice Shelf or Ronne–Filchner Ice Shelf is an Antarctic ice shelf bordering the Weddell Sea.

The Larsen Ice Shelf is a long ice shelf in the northwest part of the Weddell Sea, extending along the east coast of the Antarctic Peninsula from Cape Longing to Smith Peninsula. It is named after Captain Carl Anton Larsen, the master of the Norwegian whaling vessel Jason, who sailed along the ice front as far as 68°10' South during December 1893. In finer detail, the Larsen Ice Shelf is a series of shelves that occupy distinct embayments along the coast. From north to south, the segments are called Larsen A, Larsen B, and Larsen C by researchers who work in the area. Further south, Larsen D and the much smaller Larsen E, F and G are also named.

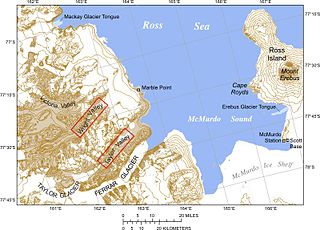

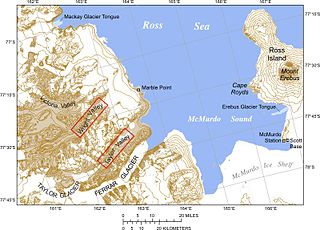

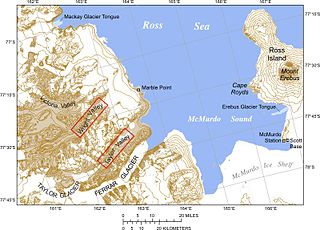

The McMurdo Sound is a sound in Antarctica, known as the southernmost passable body of water in the world, located approximately 1,300 kilometres (810 mi) from the South Pole.

Firn is partially compacted névé, a type of snow that has been left over from past seasons and has been recrystallized into a substance denser than névé. It is ice that is at an intermediate stage between snow and glacial ice. Firn has the appearance of wet sugar, but has a hardness that makes it extremely resistant to shovelling. Its density generally ranges from 0.35 g/cm3 to 0.9 g/cm3, and it can often be found underneath the snow that accumulates at the head of a glacier.

A blue ice runway is a runway constructed in Antarctic areas with no net annual snow accumulation. The density of the ice increases as air bubbles are forced out, strengthening the resultant ice surface so that aircraft landings using wheels instead of skis can be supported. Such runways simplify the transfer of materials to research stations, since wheeled aircraft can carry much heavier loads than ski-equipped aircraft.

The color of water varies with the ambient conditions in which that water is present. While relatively small quantities of water appear to be colorless, pure water has a slight blue color that becomes deeper as the thickness of the observed sample increases. The hue of water is an intrinsic property and is caused by selective absorption and scattering of blue light. Dissolved elements or suspended impurities may give water a different color.

Mertz Glacier is a heavily crevassed glacier in George V Coast of East Antarctica. It is the source of a glacial prominence that historically has extended northward into the Southern Ocean, the Mertz Glacial Tongue. It is named in honor of the Swiss explorer Xavier Mertz.

Pine Island Glacier (PIG) is a large ice stream, and the fastest melting glacier in Antarctica, responsible for about 25% of Antarctica's ice loss. The glacier ice streams flow west-northwest along the south side of the Hudson Mountains into Pine Island Bay, Amundsen Sea, Antarctica. It was mapped by the United States Geological Survey (USGS) from surveys and United States Navy (USN) air photos, 1960–66, and named by the Advisory Committee on Antarctic Names (US-ACAN) in association with Pine Island Bay.

A cryoseism, ice quake or frost quake, is a seismic event caused by a sudden cracking action in frozen soil or rock saturated with water or ice, or by stresses generated at frozen lakes. As water drains into the ground, it may eventually freeze and expand under colder temperatures, putting stress on its surroundings. This stress builds up until relieved explosively in the form of a cryoseism. The requirements for a cryoseism to occur are numerous; therefore, accurate predictions are not entirely possible and may constitute a factor in structural design and engineering when constructing in an area historically known for such events. Speculation has been made between global warming and the frequency of cryoseisms.

The Erebus Glacier Tongue is a mountain outlet glacier and the seaward extension of Erebus Glacier from Ross Island. It projects 11 kilometres (6.8 mi) into McMurdo Sound from the Ross Island coastline near Cape Evans, Antarctica. The glacier tongue varies in thickness from 50 metres (160 ft) at the snout to 300 metres (980 ft) at the point where it is grounded on the shoreline. Explorers from Robert F. Scott's Discovery Expedition (1901–1904) named and charted the glacier tongue.

Wilkins Sound is a seaway in Antarctica that is largely occupied by the Wilkins Ice Shelf. It is located on the southwest side of the Antarctic Peninsula between the concave western coastline of Alexander Island and the shores of Charcot Island and Latady Island farther to the west.

A blue iceberg is visible after the ice from above the water melts, causing the smooth portion of ice from below the water to overturn. The rare blue ice is formed from the compression of pure snow, which then develops into glacial ice.

A blue-ice area is an ice-covered area of Antarctica where wind-driven snow transport and sublimation result in net mass loss from the ice surface in the absence of melting, forming a blue surface that contrasts with the more common white Antarctic surface. Such blue-ice areas typically form when the movement of both air and ice are obstructed by topographic obstacles such as mountains that emerge from the ice sheet, generating particular climatic conditions where the net snow accumulation is exceeded by wind-driven sublimation and snow transports.