Related Research Articles

Lethal injection is the practice of injecting one or more drugs into a person for the express purpose of causing rapid death. The main application for this procedure is capital punishment, but the term may also be applied in a broader sense to include euthanasia and other forms of suicide. The drugs cause the person to become unconscious, stops their breathing, and causes a heart arrhythmia, in that order.

The electric chair is a specialized device employed for carrying out capital punishment through the process of electrocution. During its use, the individual sentenced to death is securely strapped to a specially designed wooden chair and electrocuted via strategically positioned electrodes affixed to the head and leg. This method of execution was conceptualized by Alfred P. Southwick, a dentist based in Buffalo, New York, in 1881. Over the following decade, this execution technique was developed further, aiming to provide a more humane alternative to the conventional forms of execution, particularly hanging. The electric chair was first utilized in 1890 and subsequently became known as a symbol of this method of execution.

A gas chamber is an apparatus for killing humans or other animals with gas, consisting of a sealed chamber into which a poisonous or asphyxiant gas is introduced. Poisonous agents used include hydrogen cyanide and carbon monoxide.

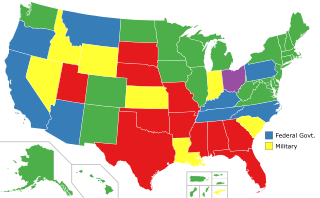

In the United States, capital punishment is a legal penalty throughout the country at the federal level, in 27 states, and in American Samoa. It is also a legal penalty for some military offenses. Capital punishment has been abolished in 23 states and in the federal capital, Washington, D.C. It is usually applied for only the most serious crimes, such as aggravated murder. Although it is a legal penalty in 27 states, 20 states currently have the ability to execute death sentences, with the other seven, as well as the federal government, being subject to different types of moratoriums.

Capital punishment is a legal penalty in the U.S. state of Oklahoma.

Wrongful execution is a miscarriage of justice occurring when an innocent person is put to death by capital punishment. Cases of wrongful execution are cited as an argument by opponents of capital punishment, while proponents say that the argument of innocence concerns the credibility of the justice system as a whole and does not solely undermine the use of the death penalty.

Hill v. McDonough, 547 U.S. 573 (2006), was a United States Supreme Court case challenging the use of lethal injection as a form of execution in the state of Florida. The Court ruled unanimously that a challenge to the method of execution as violating the Eighth Amendment to the United States Constitution properly raised a claim under 42 U.S.C. § 1983, which provides a cause of action for civil rights violations, rather than under the habeas corpus provisions. Accordingly, that the prisoner had previously sought habeas relief could not bar the present challenge.

Baze v. Rees, 553 U.S. 35 (2008), is a decision by the United States Supreme Court, which upheld the constitutionality of a particular method of lethal injection used for capital punishment.

Capital punishment in Alabama is a legal penalty. Alabama has the highest per capita capital sentencing rate in the United States. In some years, its courts impose more death sentences than Texas, a state that has a population five times as large. However, Texas has a higher rate of executions both in absolute terms and per capita.

Wilkerson v. Utah, 99 U.S. 130 (1879), is a United States Supreme Court case in which the Court affirmed the judgment of the Supreme Court of the Territory of Utah in stating that execution by firing squad, as prescribed by the Utah territorial statute, was not cruel and unusual punishment under the Eighth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

William Earl Lynd was an American murderer who was executed by the state of Georgia for the 1988 murder of his then-girlfriend, Ginger Moore. He was notable for being the first person to be executed in the United States after the Baze v. Rees ruling.

Participation of medical professionals in American executions is a controversial topic, due to its moral and legal implications. The practice is proscribed by the American Medical Association, as defined in its Code of Medical Ethics. The American Society of Anesthesiologists endorses this position, stating that lethal injections "can never conform to the science, art and practice of anesthesiology".

Romell Broom was an American death row inmate who was convicted of murder, kidnapping and rape. He was sentenced to death for the 1984 murder of 14-year-old Tryna Middleton. Broom was scheduled to be executed on September 15, 2009, but after executioners failed to locate a vein he was granted a reprieve. A second execution attempt was scheduled for June 2020, which was delayed until March 2022. Broom died from COVID-19 in prison before the sentence could be carried out.

Glossip v. Gross, 576 U.S. 863 (2015), was a United States Supreme Court case in which the Court held, 5–4, that lethal injections using midazolam to kill prisoners convicted of capital crimes do not constitute cruel and unusual punishment under the Eighth Amendment to the United States Constitution. The Court found that condemned prisoners can only challenge their method of execution after providing a known and available alternative method.

Richard Eugene Glossip is an American prisoner currently on death row at Oklahoma State Penitentiary after being convicted of commissioning the 1997 murder of Barry Van Treese. The man who murdered Van Treese, Justin Sneed, had a "meth habit" and agreed to plead guilty in exchange for testifying against Glossip. Sneed received a life sentence without parole. Glossip's case has attracted international attention due to the unusual nature of his conviction, namely that there was little or no corroborating evidence, with the first case against him described as "extremely weak" by the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals.

Capital punishment is a legal penalty in the U.S. state of Kentucky.

Bucklew v. Precythe, 587 U.S. ___ (2019), was a United States Supreme Court case regarding the standards for challenging methods of capital punishment under the Eighth Amendment to the United States Constitution. In a 5–4 decision, the Court held that when a convict sentenced to death challenges the State's method of execution due to claims of excessive pain, the convict must show that other alternative methods of execution exist and clearly demonstrate they would cause less pain than the state-determined one. The Court's opinion emphasized the precedential force of its prior decisions in Baze v. Rees and Glossip v. Gross.

The execution of John Grant took place in the U.S. state of Oklahoma by means of lethal injection. Grant was sentenced to death for the 1998 murder of prison cafeteria worker Gay Carter.

Glossip v. Chandler is a United States District Court for the Western District of Oklahoma case in which the plaintiffs challenged the State of Oklahoma's execution protocol. The initial lawsuit, Glossip v. Gross, rose to the United States Supreme Court in 2015 at the preliminary injunction stage and involved an earlier version of Oklahoma's lethal injection protocol. The case was reopened in the District Court in 2020 following an end to Oklahoma's moratorium on executions.

References

- ↑ "Grant Schulte, Associated Press, Company: Nebraska shouldn't have gotten death penalty drug". Lincoln Journal Star . April 13, 2017. Archived from the original on September 5, 2017. Retrieved September 5, 2017.

- ↑ "Alan Blinder, Alabama Inmate, 75, Hopes to Dodge Death for an Eighth Time". The New York Times . May 24, 2017. Archived from the original on September 5, 2017. Retrieved September 5, 2017.

- ↑ "Zusha Elinson and Beth Reinhard, Effort Expands to Boost Punishment for Police Killers" . The Wall Street Journal . June 8, 2017. Archived from the original on September 5, 2017. Retrieved September 5, 2017.

- ↑ "Three States Accounted For 80 Percent Of Executions in 2014". The Huffington Post . Archived from the original on December 20, 2014. Retrieved December 18, 2014.

- ↑ Latzer, Barry (October 27, 2010). Death Penalty Cases: Leading U.S. Supreme Court Cases on Capital Punishment. Elsevier. p. 21. ISBN 978-0123820259.

- ↑ "1000+ Death Penalty Links". The ClarkCounty Prosecuting Attorney. Retrieved September 5, 2017.

- ↑ "Arguments for and Against the Death Penalty" . Retrieved July 1, 2022.

- ↑ "Death Penalty Census Codebook" (PDF).

- ↑ "Death Penalty Census Database" . Retrieved June 29, 2022.

- ↑ "List of Projects financed under EIDHR" (PDF). European Commission . Archived from the original (PDF) on August 11, 2011. Retrieved August 20, 2017.

- ↑ "About Us". Death Penalty information Center. Retrieved August 9, 2019.

- ↑ "The Death Penalty in 2022: Year End Report" (PDF). Death Penalty Information Center. Retrieved February 1, 2023.

- ↑ "Reports". Death Penalty information Center. Archived from the original on September 5, 2017. Retrieved September 5, 2017.

- ↑ "Behind the Curtain: Secrecy and the Death Penalty in the United States" (PDF). Death Penalty information Center. Retrieved August 9, 2019.

- ↑ "Enduring Injustice: The Persistence of Racial Discrimination in the U.S. Death Penalty" (PDF). Death Penalty information Center. Retrieved October 29, 2020.

- ↑ "Colleen Long, Report: Death penalty cases show history of racial disparity". Associated Press. 15 September 2020. Retrieved September 15, 2020.

- ↑ "Innocence and the Death Penalty: Assessing The Danger of Mistaken Executions". Death Penalty Information Center. October 21, 1993. Archived from the original on September 5, 2017. Retrieved September 5, 2017.

- ↑ "Innocence Database". Death Penalty Information Center. Retrieved February 1, 2023.

- ↑ "Additional Innocence Information". Death Penalty Information Center. Archived from the original on September 5, 2017. Retrieved September 5, 2017.

- ↑ "DPIC Special Report: The Innocence Epidemic". Death Penalty Information Center. Retrieved July 1, 2022.

- 1 2 "Botched Executions". Death Penalty Information Center. Retrieved August 9, 2019.

- ↑ Baze v. Rees oral arguments.

- ↑ "Glossip v. Gross" (PDF).