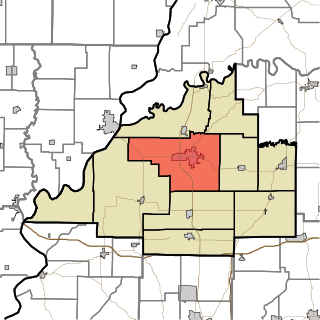

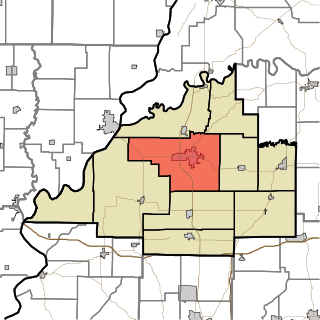

Gibson County is a county in the southwestern part of the U.S. state of Indiana. As of the 2010 United States Census, the population was 33,503. The county seat is Princeton.

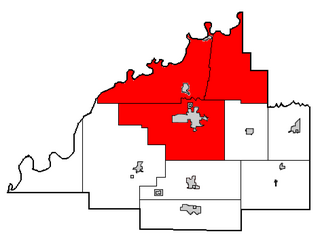

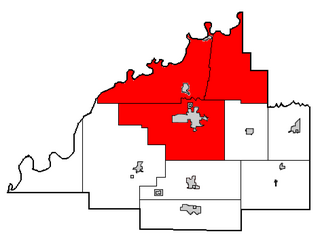

Princeton is a city in Patoka Township, Gibson County, Indiana, United States. The population was 8,644 at the 2010 census, and it is part of the greater Evansville, Indiana, Metropolitan Area. The city is the county seat of and the largest city in Gibson County.

Evansville is a city in, and the county seat of, Vanderburgh County, Indiana. The population was 117,429 at the 2010 census, making it the state's third-most populous city after Indianapolis and Fort Wayne, the largest city in Southern Indiana, and the 232nd-most populous city in the United States. It is the commercial, medical, and cultural hub of Southwestern Indiana and the Illinois–Indiana–Kentucky tri-state area, home to over 911,000 people. The 38th parallel crosses the north side of the city and is marked on Interstate 69.

The Patoka River is a 167-mile-long (269 km) tributary of the Wabash River in southwestern Indiana in the United States. It drains a largely rural area of forested bottomland and agricultural lands among the hills north of Evansville.

Angel Mounds State Historic Site, an expression of the Mississippian culture, is an archaeological site managed by the Indiana State Museum and Historic Sites that includes more than 600 acres of land about 8 miles (13 km) southeast of present-day Evansville, in Vanderburgh and Warrick counties in Indiana. The large residential and agricultural community was constructed and inhabited from AD 1100 to AD 1450, and served as the political, cultural, and economic center of the Angel chiefdom. It extended within 120 miles (190 km) of the Ohio River valley to the Green River in present-day Kentucky. The town had as many as 1,000 inhabitants at its peak, and included a complex of thirteen earthen mounds, hundreds of home sites, a palisade (stockade), and other structures.

Indiana Landmarks is America's largest private statewide historic preservation organization. Founded in 1960 as Historic Landmarks Foundation of Indiana by a volunteer group of civic and business leaders led by Indianapolis pharmaceutical executive Eli Lilly, the organization is a private non-governmental organization with nearly 6,000 members and an endowment of over $40-million. The organization simplified its name to Indiana Landmarks in 2010.

The Gibson Generating Station is a coal-burning power plant located at the northernmost end of Montgomery Township, Gibson County, Indiana, United States. It is close to the Wabash River, 1.5 miles southeast of Mount Carmel, Illinois, 2 miles south of the mouth of the Patoka River, and 4 miles south of the mouth of the White River. The closest Indiana communities are Owensville 7.5 miles to the southeast of the plant, and Princeton, 10.5 miles to the east. With a 2013 aggregate output capacity among its five units of 3,345 megawatts, it is the largest power plant run by Duke Energy, the tenth-largest electrical plant in the United States, With the reduction of Nanticoke Generating Station, it became the largest coal power plant in North America by generated power late in 2012. Also on the grounds of the facility is a 3,000-acre (12 km2) large man-made lake called Gibson Lake which is used as a cooling pond for the plant. Neighboring the plant is a Duke-owned, publicly accessible access point to the Wabash River near a small island that acts as a wildlife preserve. This is the nearest boat-ramp to Mount Carmel on the Indiana side of the river. Located immediately south of Gibson Lake, the plant's cooling pond, is the Cane Ridge National Wildlife Refuge, the newest unit of the Patoka River National Wildlife Refuge and Management Area. Opened in August 2006, this 26-acre (11 ha) area serves as a nesting ground for the least tern, a rare bird. Cane Ridge NWR is reportedly the easternmost nesting ground for the bird in the U.S. The Gibson Generating Station is connected to the power grid via five 345 kV and one 138 kV transmission lines to 79 Indiana counties including the Indianapolis area and a sixth 345 kV line running from GGS to Evansville and Henderson, owned by Vectren and Kenergy.

Lyles Consolidated School is a historic school in Lyles Station, Indiana. The third school to be located in Lyles Station, it was opened in 1919 and used until 1958. Abandoned for nearly forty years, it had deteriorated almost to the point of total collapse by 1997. The Lyles Station Historic Preservation Corporation was founded in June 1997, to preserve and promote the history of the Lyles Station community. Its major project was restoration of the schoolhouse, intending to use it as a living history museum to educate others both about Lyles Station's history and the daily school routine in the early twentieth century. The school was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1999. Restoration of the site was completed in 2003.

Montgomery Township is the largest of the ten townships in Gibson County, Indiana as well as one of the largest townships by area in Southwestern Indiana. As of the 2010 census, its population was 3,996 and it contained 1,645 housing units, 75% of which live in areas adjacent to Owensville. Montgomery Township is served by the South Gibson School Corporation. Gibson Generating Station and Gibson Lake are located at the northern end of Montgomery Township.

Patoka Township is one of ten townships in Gibson County, Indiana, United States. As of the 2010 census, its population was 11,864 and it contained 5,341 housing units. It is the largest township in population, accounting for roughly 30% of the county's total population.

The South Gibson School Corporation is the largest of the three public school governing institutions in both enrollment and territory covered in Gibson County, Indiana as well as one of the ten largest in enrollment in Southwestern Indiana. The SGSC is responsible for a district including four townships of southern and southwestern Gibson County; Johnson, Montgomery, Union, Wabash, and parts of Barton, Center and Patoka Townships within Gibson County as well as drawing in students from Northern Vanderburgh and Posey Counties. It consists of a superintendent, a five-member school board, eight principals and vice principals and employs around 190 teachers and specialists. The SGSC's renovation of the then-35-year-old Gibson Southern High School was complete as of 2010-11 School Year.

The North Gibson School Corporation is the second largest of the three public school governing institutions in Gibson County, Indiana, United States as well as one of the twenty largest in enrollment in Southwestern Indiana. The NGSC is responsible for a district including three townships of northern and northeastern Gibson County; Patoka, Washington, and White River. However, the Gibson-Pike-Warrick Special Education Cooperative sends the majority of the special needs students from Pike and Gibson Counties to Princeton Community High School, the high school of the district.

The Underground Railroad in Indiana was part of a larger, unofficial, and loosely-connected network of groups and individuals who aided and facilitated the escape of runaway slaves from the southern United States. The network in Indiana gradually evolved in the 1830s and 1840s, reached its peak during the 1850s, and continued until slavery was abolished throughout the United States at the end of the American Civil War in 1865. It is not known how many fugitive slaves escaped through Indiana on their journey to Michigan and Canada. An unknown number of Indiana's abolitionists, anti-slavery advocates, and people of color, as well as Quakers and other religious groups illegally operated stations along the network. Some of the network's operatives have been identified, including Levi Coffin, the best-known of Indiana's Underground Railroad leaders. In addition to shelter, network agents provided food, guidance, and, in some cases, transportation to aid the runaways.

Roberts Chapel, is a non-denominational church that was originally built in 1847 at Roberts Settlement, one of Indiana's early black pioneer communities. The rural church, whose main building dates from 1858, is located near the present-day town of Atlanta in rural Jackson Township, Hamilton County, Indiana. The chapel was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1996.

The Bethel A.M.E. Church, known in its early years as Indianapolis Station or the Vermont Street Church, is a historic African Methodist Episcopal Church in Indianapolis, Indiana. Organized in 1836, it is the city's oldest African-American congregation. The three-story church on West Vermont Street dates to 1869 and was added to the National Register in 1991. The surrounding neighborhood, once the heart of downtown Indianapolis's African American community, significantly changed with post-World War II urban development that included new hotels, apartments, office space, museums, and the Indiana University–Purdue University at Indianapolis campus. In 2016 the congregation sold their deteriorating church, which will be used in a future commercial development. The congregation built a new worship center at 6417 Zionsville Road in Pike Township, Marion County, Indiana.

Weaver is an unincorporated community in Liberty Township, Grant County, Indiana. Weaver's first settlers were free people of color who migrated from North Carolina and South Carolina to Grant County in the early 1840s. The neighborhood was originally known as Crossroad; however, it was later renamed Weaver in honor of a prominent family of the community. The rural settlement reached its peak in the late 1800s, when its population reportedly reached 2,000. Many of its residents left the community for higher-paying jobs in larger towns during the Indiana's natural gas boom, but more than 100 families remained in the settlement in the early 1920s. Weaver, as with most of Indiana's black rural settlements, no longer exists as a self-contained community, but Weaver Cemetery remains as a community landmark.

Beech Settlement was a rural settlement in Ripley Township, Rush County, Indiana. Its early settlers were free people of color and a small number of free blacks, who came to the area with Quakers. Beech was one of Indiana's early black rural settlements and also one of its largest. The rural neighborhood received its name because of a large stand of beech trees in its vicinity. By 1835 the farming community had a population of 400 residents, but largely due to changing economic conditions, including rising costs of farming, the settlement's population began to decline after 1870. Fewer than six of the Beech families remained by 1920. As with most of Indiana's black rural settlements, Beech Settlement no longer exists. Few major points of interest remain; however, the community's Mount Pleasant Beech Church serves as the site for annual reunions of its friends and the descendants of former residents.

Roberts Settlement was an early rural settlement in Jackson Township, Hamilton County, Indiana. Dating from the 1830s, its first settlers were free people of color, most of whom migrated from Beech Settlement, located 40 miles (64 km) southeast in rural Rush County, Indiana. Many of Roberts Settlement's early pioneers were born in eastern North Carolina and Virginia. Some of its settlers were ex-slaves. The neighborhood received its name from the large contingent of its residents who had the surname of Roberts. By the 1870s the farming community had a population of approximately 300 residents. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the settlement's population began to decline, largely due to changing economic conditions that included rising costs of farming. Fewer than six families remained at the settlement by the mid-1920s. Most of Indiana's early black rural settlements, including Roberts Settlement, no longer exist. Roberts Chapel, listed on the National Register of Historic Places, serves as the site for the community's annual reunions of its friends and the descendants of former residents.

Indiana State Federation of Colored Women's Clubs, also known as the Minor House, is a historic National Association of Colored Women's Clubs clubhouse in Indianapolis, Indiana. The two-and-one-half-story "T"-plan building was originally constructed in 1897 as a private dwelling for John and Sarah Minor; however, since 1927 it has served as the headquarters of the Indiana State Federation of Colored Women's Clubs, a nonprofit group of African American women. The Indiana federation was formally organized on April 27, 1904, in Indianapolis and incorporated in 1927. The group's Colonial Revival style frame building sits on a brick foundation and has a gable roof with hipped dormers. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1987.

The Union Literary Institute, located in rural Randolph County, Indiana, at 8605 East County Road 600 South, Union City, Indiana, was a school founded in 1846 by abolitionist Quakers and free blacks from Ohio, Kentucky, and North Carolina, after the Indiana Legislature decreed in 1843 that "colored students" could not attend the public schools. When founded it was one of only a handful of American schools in which black and white students studied together; it was the first in Indiana, The school closed briefly because of the Civl War. It published a magazine, and survived until 1880.