The Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) of June 18, 1934, or the Wheeler–Howard Act, was U.S. federal legislation that dealt with the status of American Indians in the United States. It was the centerpiece of what has been often called the "Indian New Deal".

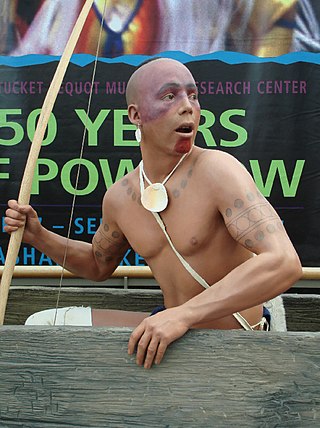

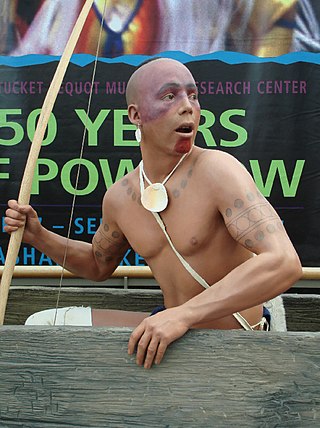

The Pequot are a Native American people of Connecticut. The modern Pequot are members of the federally recognized Mashantucket Pequot Tribe, four other state-recognized groups in Connecticut including the Eastern Pequot Tribal Nation, or the Brothertown Indians of Wisconsin. They historically spoke Pequot, a dialect of the Mohegan-Pequot language, which became extinct by the early 20th century. Some tribal members are undertaking revival efforts.

The Mashantucket Pequot Tribal Nation is a federally recognized American Indian tribe in the state of Connecticut. They are descended from the Pequot people, an Algonquian-language tribe that dominated the southern New England coastal areas, and they own and operate Foxwoods Resort Casino within their reservation in Ledyard, Connecticut. As of 2018, Foxwoods Resort Casino is one of the largest casinos in the world in terms of square footage, casino floor size, and number of slot machines, and it was one of the most economically successful in the United States until 2007, but it became deeply in debt by 2012 due to its expansion and changing conditions.

The Oneida people are a Native American tribe and First Nations band. They are one of the five founding nations of the Iroquois Confederacy in the area of upstate New York, particularly near the Great Lakes.

The Catawba, also known as Issa, Essa or Iswä but most commonly Iswa, are a federally recognized tribe of Native Americans, known as the Catawba Indian Nation. Their current lands are in South Carolina, on the Catawba River, near the city of Rock Hill. Their territory once extended into North Carolina, as well, and they still have legal claim to some parcels of land in that state. They were once considered one of the most powerful Southeastern tribes in the Carolina Piedmont, as well as one of the most powerful tribes in the South as a whole, with other, smaller tribes merging into the Catawba as their post-contact numbers dwindled due to the effects of colonization on the region.

An American Indian reservation is an area of land held and governed by a U.S. federal government-recognized Native American tribal nation, whose government is autonomous, subject to regulations passed by the United States Congress and administered by the United States Bureau of Indian Affairs, and not to the U.S. state government in which it is located. Some of the country's 574 federally recognized tribes govern more than one of the 326 Indian reservations in the United States, while some share reservations, and others have no reservation at all. Historical piecemeal land allocations under the Dawes Act facilitated sales to non–Native Americans, resulting in some reservations becoming severely fragmented, with pieces of tribal and privately held land being treated as separate enclaves. This jumble of private and public real estate creates significant administrative, political, and legal difficulties.

The Menominee are a federally recognized tribe of Native Americans officially known as the Menominee Indian Tribe of Wisconsin. Their land base is the Menominee Indian Reservation in Wisconsin. Their historic territory originally included an estimated 10 million acres (40,000 km2) in present-day Wisconsin and the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. The tribe currently has about 8,700 members.

There are four treaties of Buffalo Creek, named for the Buffalo River in New York. The Second Treaty of Buffalo Creek, also known as the Treaty with the New York Indians, 1838, was signed on January 15, 1838 between the Seneca Nation, Mohawk nation, Cayuga nation, Oneida Indian Nation, Onondaga (tribe), Tuscarora (tribe) and the United States. It covered land sales of tribal reservations under the U.S. Indian Removal program, by which they planned to move most eastern tribes to Kansas Territory west of the Mississippi River.

The Oneida Indian Nation (OIN) or Oneida Nation is a federally recognized tribe of Oneida people in the United States. The tribe is headquartered in Verona, New York, where the tribe originated and held territory prior to European colonialism, and continues to hold territory today. They are Iroquoian-speaking people, and one of the Five Nations of the Iroquois Confederacy, or Haudenosaunee. The Oneida are known as "America's first allies" as they were the first, and one of the few, Iroquois nations to support the American cause. Three other federally recognized Oneida tribes operate in locations where they migrated or were removed to during and after the American Revolutionary War: one in Wisconsin in the United States, and two in Ontario, Canada.

The Brothertown Indians, located in Wisconsin, are a possible Native American tribe formed in the late 18th century from communities of so-called "praying Indians", descended from Christianized Pequot, Narragansett, Montauk, Tunxis, Niantic, and Mohegan (Algonquian-speaking) tribes of southern New England and eastern Long Island, New York. In the 1780s after the American Revolutionary War, they migrated from New England into New York state, where they accepted land from the Iroquois Oneida Nation in Oneida County.

The Stockbridge–Munsee Community, also known as the Mohican Nation Stockbridge–Munsee Band, is a federally recognized Native American tribe formed in the late eighteenth century from communities of so-called "praying Indians", descended from Christianized members of two distinct groups: Mohican and Wappinger from the praying town of Stockbridge, Massachusetts, and Munsee (Lenape), from the area where present-day New York, Pennsylvania and New Jersey meet. Their land-base, the Stockbridge–Munsee Indian Reservation, consists of a checkerboard of 24.03 square miles (62.2 km2) in the towns of Bartelme and Red Springs in Shawano County, Wisconsin. Among their enterprises is the North Star Mohican Resort and Casino.

The Seneca–Cayuga Nation is one of three federally recognized tribes of Seneca people in the United States. It includes the Cayuga people and is based in Oklahoma, United States. The tribe had more than 5,000 people in 2011. They have a tribal jurisdictional area in the northeast corner of Oklahoma and are headquartered in Grove. They are descended from Iroquoian peoples who had relocated to Ohio from New York state in the mid-18th century.

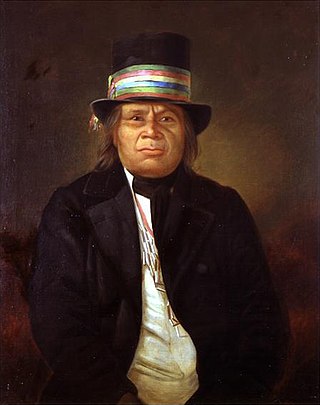

Purcell Powless was the tribal chairman of the Oneida Nation of Wisconsin, United States.

Aboriginal title in New York refers to treaties, purchases, laws and litigation associated with land titles of aboriginal peoples of New York, in particular, to dispossession of those lands by actions of European Americans. The European purchase of lands from indigenous populations dates back to the legendary Dutch purchase of Manhattan in 1626, "the most famous land transaction of all." More than any other state, New York disregarded the Confederation Congress Proclamation of 1783 and the follow-on Nonintercourse Acts, purchasing the majority of the state directly from the Iroquois nations without federal involvement or ratification.

The Kickapoo Tribe of Indians of the Kickapoo Reservation in Kansas is one of three Federally recognized tribes of Kickapoo people. The other Kickapoo tribes in the United States are the Kickapoo Traditional Tribe of Texas and the Kickapoo Tribe of Oklahoma. The Tribu Kikapú are a distinct subgroup of the Oklahoma Kickapoo and reside on a hacienda near Múzquiz Coahuila, Mexico; they also have a small band located in the Mexican states of Sonora and Durango.

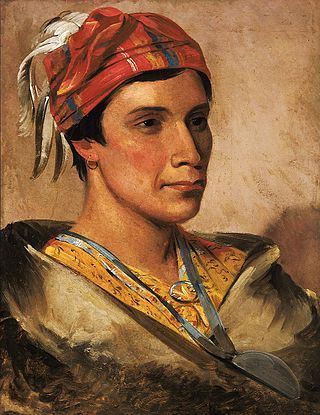

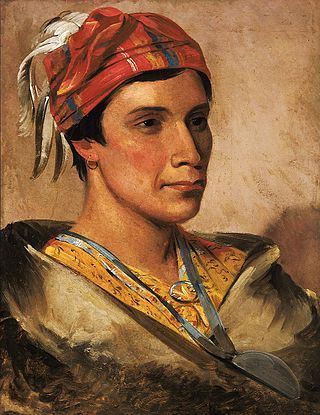

Cornelius Hill or Onangwatgo was the last hereditary chief of the Oneida Nation, and fought to preserve his people's lands and rights under various treaties with the United States government. A lifelong Episcopalian, he was ordained a priest of the Episcopal Church in the United States of America at age 69, and ministered to his people until shortly before his death.

Laura Cornelius Kellogg ("Minnie") ("Wynnogene"), was an Oneida leader, author, orator, activist and visionary. Kellogg, a descendant of distinguished Oneida leaders, was a founder of the Society of American Indians. Kellogg was an advocate for the renaissance and sovereignty of the Six Nations of the Iroquois, and fought for communal tribal lands, tribal autonomy and self-government. Popularly known as "Indian Princess Wynnogene," Kellogg was the voice of the Oneidas and Haudenosaunee people in national and international forums. During the 1920s and 1930s, Kellogg and her husband, Orrin J. Kellogg, pursued land claims in New York on behalf of the Six Nations people. Kellogg's "Lolomi Plan" was a Progressive Era alternative to Bureau of Indian Affairs control emphasizing indigenous American self-sufficiency, cooperative labor and organization, and capitalization of labor. According to historian Laurence Hauptman, "Kellogg helped transform the modern Iroquois, not back into their ancient League, but into major actors, activists and litigants in the modern world of the 20th century Indian politics."

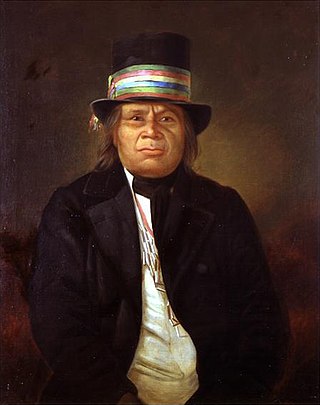

Daniel Bread was an Oneida political and cultural leader who helped the Oneida preserve their culture while adapting to new realities during their transplantation from New York to Wisconsin. He was frequently described as a "principal chief", "head chief", or "sachem" by the Oneida but held no hereditary position and was not an officially condoled chief. Bread was a pragmatist who found ways to compromise between "promoting tribal sovereignty and treaty rights" and cooperating with federal and state officials. He played a major role in adapting the Iroquois condolence ceremony into a July 4 celebration that recognized the alliance of the Oneida with George Washington during the American Revolution. At age 14, Bread was part of the defense of Sackets Harbor during the Battle of Big Sandy Creek.

The Everett Report of 1922 was a New York State Assembly report compiled by a legislative commission led by Edward A. Everett. It concluded that "the Iroquois were fraudulently dispossessed of over six million acres of land in New York." However, the report was "buried" by New York State and not published until 1971.

Mary Cornelius Winder was a Native American activist who wrote a series of letters to the federal government related to Oneida Indian Nation ancestral land claims.