Giant cell arteritis (GCA), also called temporal arteritis, is an inflammatory autoimmune disease of large blood vessels. Symptoms may include headache, pain over the temples, flu-like symptoms, double vision, and difficulty opening the mouth. Complication can include blockage of the artery to the eye with resulting blindness, as well as aortic dissection, and aortic aneurysm. GCA is frequently associated with polymyalgia rheumatica.

Rheumatology is a branch of medicine devoted to the diagnosis and management of disorders whose common feature is inflammation in the bones, muscles, joints, and internal organs. Rheumatology covers more than 100 different complex diseases, collectively known as rheumatic diseases, which includes many forms of arthritis as well as lupus and Sjögren's syndrome. Doctors who have undergone formal training in rheumatology are called rheumatologists.

The erythrocyte sedimentation rate is the rate at which red blood cells in anticoagulated whole blood descend in a standardized tube over a period of one hour. It is a common hematology test, and is a non-specific measure of inflammation. To perform the test, anticoagulated blood is traditionally placed in an upright tube, known as a Westergren tube, and the distance which the red blood cells fall is measured and reported in millimetres at the end of one hour.

Erythema infectiosum, fifth disease, or slapped cheek syndrome is one of several possible manifestations of infection by parvovirus B19. Fifth disease typically presents as a rash and is more common in children. While parvovirus B19 can affect humans of all ages, only two out of ten individuals will present with physical symptoms.

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) is a type of arthritis characterized by long-term inflammation of the joints of the spine, typically where the spine joins the pelvis. Occasionally, areas affected may include other joints such as the shoulders or hips. Eye and bowel problems may occur as well as back pain. Joint mobility in the affected areas generally worsens over time.

Prednisone is a glucocorticoid medication mostly used to suppress the immune system and decrease inflammation in conditions such as asthma, COPD, and rheumatologic diseases. It is also used to treat high blood calcium due to cancer and adrenal insufficiency along with other steroids. It is taken by mouth.

Primate erythroparvovirus 1, generally referred to as B19 virus(B19V),parvovirus B19 or sometimes erythrovirus B19, is the first known human virus in the family Parvoviridae, genus Erythroparvovirus; it measures only 23–26 nm in diameter. The name is derived from Latin parvum, meaning small, reflecting the fact that B19 ranks among the smallest DNA viruses. B19 virus is most known for causing disease in the pediatric population; however, it can also affect adults. It is the classic cause of the childhood rash called fifth disease or erythema infectiosum, or "slapped cheek syndrome".

Vasculitis is a group of disorders that destroy blood vessels by inflammation. Both arteries and veins are affected. Lymphangitis is sometimes considered a type of vasculitis. Vasculitis is primarily caused by leukocyte migration and resultant damage. Although both occur in vasculitis, inflammation of veins (phlebitis) or arteries (arteritis) on their own are separate entities.

Henoch–Schönlein purpura (HSP), also known as IgA vasculitis, is a disease of the skin, mucous membranes, and sometimes other organs that most commonly affects children. In the skin, the disease causes palpable purpura, often with joint pain and abdominal pain. With kidney involvement, there may be a loss of small amounts of blood and protein in the urine, but this usually goes unnoticed; in a small proportion of cases, the kidney involvement proceeds to chronic kidney disease. HSP is often preceded by an infection, such as a throat infection.

Polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) is a systemic necrotizing inflammation of blood vessels (vasculitis) affecting medium-sized muscular arteries, typically involving the arteries of the kidneys and other internal organs but generally sparing the lungs' circulation. Small aneurysms are strung like the beads of a rosary, therefore making this "rosary sign" an important diagnostic feature of the vasculitis. PAN is sometimes associated with infection by the hepatitis B or hepatitis C virus. The condition may be present in infants.

Arteritis is the inflammation of the walls of arteries, usually as a result of infection or autoimmune response. Arteritis, a complex disorder, is still not entirely understood. Arteritis may be distinguished by its different types, based on the organ systems affected by the disease. A complication of arteritis is thrombosis, which can be fatal. Arteritis and phlebitis are forms of vasculitis.

Posterior ischemic optic neuropathy (PION) is a medical condition characterized by damage to the retrobulbar portion of the optic nerve due to inadequate blood flow (ischemia) to the optic nerve. Despite the term posterior, this form of damage to the eye's optic nerve due to poor blood flow also includes cases where the cause of inadequate blood flow to the nerve is anterior, as the condition describes a particular mechanism of visual loss as much as the location of damage in the optic nerve. In contrast, anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (AION) is distinguished from PION by the fact that AION occurs spontaneously and on one side in affected individuals with predisposing anatomic or cardiovascular risk factors.

A giant cell is a mass formed by the union of several distinct cells, often forming a granuloma.

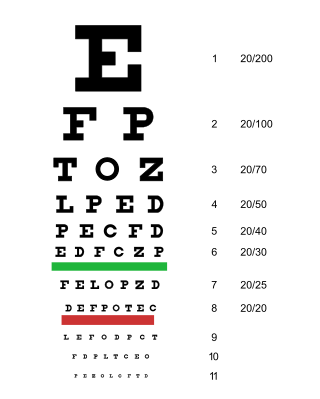

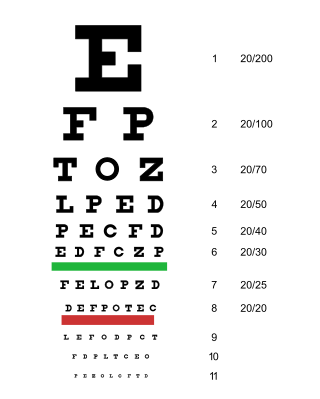

Arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy is the cause of vision loss that occurs in temporal arteritis. Temporal arteritis is an inflammatory disease of medium-sized blood vessels that happens especially with advancing age. AAION occurs in about 15-20 percent of patients with temporal arteritis. Damage to the blood vessels supplying the optic nerves leads to insufficient blood supply (ischemia) to the nerve and subsequent optic nerve fiber death. Most cases of AAION result in nearly complete vision loss first to one eye. If the temporal arteritis is left untreated, the fellow eye will likely suffer vision loss as well within 1–2 weeks. Arteritic AION falls under the general category of anterior ischemic optic neuropathy, which also includes non-arteritic AION. AION is considered an eye emergency, immediate treatment is essential to rescue remaining vision.

A neuromuscular disease is any disease affecting the peripheral nervous system (PNS), the neuromuscular junctions, or skeletal muscles, all of which are components of the motor unit. Damage to any of these structures can cause muscle atrophy and weakness. Issues with sensation can also occur.

Aortitis is the inflammation of the aortic wall. The disorder is potentially life-threatening and rare. It is reported that there are only 1–3 new cases of aortitis per year per million people in the United States and Europe. Aortitis is most common in people 10 to 40 years of age.

Cerebral vasculitis is vasculitis involving the brain and occasionally the spinal cord. It affects all of the vessels: very small blood vessels (capillaries), medium-size blood vessels, or large blood vessels. If blood flow in a vessel with vasculitis is reduced or stopped, the parts of the body that receive blood from that vessel begins to die. It may produce a wide range of neurological symptoms, such as headache, skin rashes, feeling very tired, joint pains, difficulty moving or coordinating part of the body, changes in sensation, and alterations in perception, thought or behavior, as well as the phenomena of a mass lesion in the brain leading to coma and herniation. Some of its signs and symptoms may resemble multiple sclerosis. 10% have associated bleeding in the brain.

Necrotizing vasculitis, also called systemic necrotizing vasculitus, is a category of vasculitis, comprising vasculitides that present with necrosis. Examples include giant cell arteritis, microscopic polyangiitis, and granulomatosis with polyangiitis. ICD-10 uses the variant "necrotizing vasculopathy". ICD-9, while classifying these conditions together, does not use a dedicated phrase, instead calling them "polyarteritis nodosa and allied conditions".

Acute visual loss is a rapid loss of the ability to see. It is caused by many ocular conditions like retinal detachment, glaucoma, macular degeneration, and giant cell arteritis, etc.

Amplified musculoskeletal pain syndrome (AMPS) is a long-term condition characterized by amplified pain without an identifiable physical cause. Other common symptoms include changes in the skin texture, color, and temperature; changes in hair and nail growth; skin sensitivity to touch, also known as allodynia; and dizziness, especially when going to a standing position after sitting. In up to 80% of cases, symptoms are caused by psychological trauma or psychological stress. AMPS is also commonly caused by physical injury or illness. Other possible causes of AMPS include Ehlers-danlos syndrome, myositis, arthritis, and other rheumatologic diseases. Due to the nature of the condition, AMPS is often not diagnosed when it first presents. AMPS is diagnosed through a review of a patient's medical history, as well as multiple tests to rule out the diagnosis of other conditions, such as bone fracture.