Thrombosis is the formation of a blood clot inside a blood vessel, obstructing the flow of blood through the circulatory system. When a blood vessel is injured, the body uses platelets (thrombocytes) and fibrin to form a blood clot to prevent blood loss. Even when a blood vessel is not injured, blood clots may form in the body under certain conditions. A clot, or a piece of the clot, that breaks free and begins to travel around the body is known as an embolus.

Venous thrombosis is the blockage of a vein caused by a thrombus. A common form of venous thrombosis is deep vein thrombosis (DVT), when a blood clot forms in the deep veins. If a thrombus breaks off (embolizes) and flows to the lungs to lodge there, it becomes a pulmonary embolism (PE), a blood clot in the lungs. The conditions of DVT only, DVT with PE, and PE only, are all captured by the term venous thromboembolism (VTE).

Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) is a condition in which blood clots form throughout the body, blocking small blood vessels. Symptoms may include chest pain, shortness of breath, leg pain, problems speaking, or problems moving parts of the body. As clotting factors and platelets are used up, bleeding may occur. This may include blood in the urine, blood in the stool, or bleeding into the skin. Complications may include organ failure.

Antiphospholipid syndrome, or antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, is an autoimmune, hypercoagulable state caused by antiphospholipid antibodies. APS can lead to blood clots (thrombosis) in both arteries and veins, pregnancy-related complications, and other symptoms like low platelets, kidney disease, heart disease, and rash. Although the exact etiology of APS is still not clear, genetics is believed to play a key role in the development of the disease. Diagnosis is made based on symptoms and testing, but sometimes research criteria are used to aid in diagnosis. The research criteria for definite APS requires one clinical event and two positive blood test results spaced at least three months apart that detect lupus anticoagulant, anti-apolipoprotein antibodies, and/or anti-cardiolipin antibodies.

Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) is a type of venous thrombosis involving the formation of a blood clot in a deep vein, most commonly in the legs or pelvis. A minority of DVTs occur in the arms. Symptoms can include pain, swelling, redness, and enlarged veins in the affected area, but some DVTs have no symptoms.

Budd–Chiari syndrome is a very rare condition, affecting one in a million adults. The condition is caused by occlusion of the hepatic veins that drain the liver. The symptoms are non-specific and vary widely, but it may present with the classical triad of abdominal pain, ascites, and liver enlargement. It is usually seen in younger adults, with the median age at diagnosis between the ages of 35 and 40, and it has a similar incidence in males and females. The syndrome can be fulminant, acute, chronic, or asymptomatic. Subacute presentation is the most common form.

Thrombophilia is an abnormality of blood coagulation that increases the risk of thrombosis. Such abnormalities can be identified in 50% of people who have an episode of thrombosis that was not provoked by other causes. A significant proportion of the population has a detectable thrombophilic abnormality, but most of these develop thrombosis only in the presence of an additional risk factor.

Thrombophlebitis is a phlebitis related to a thrombus. When it occurs repeatedly in different locations, it is known as thrombophlebitis migrans.

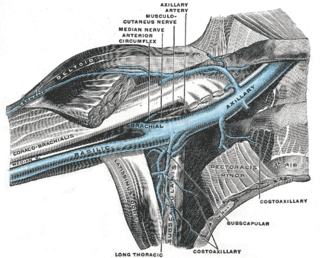

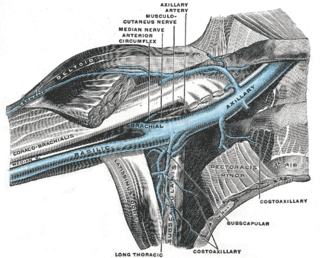

Paget–Schroetter disease is a form of upper extremity deep vein thrombosis (DVT), a medical condition in which blood clots form in the deep veins of the arms. These DVTs typically occur in the axillary and/or subclavian veins.

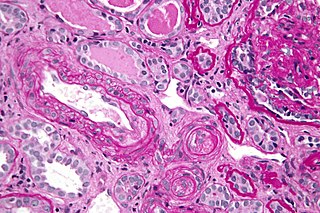

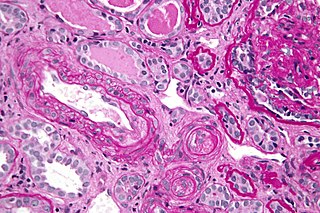

Renal vein thrombosis (RVT) is the formation of a clot in the vein that drains blood from the kidneys, ultimately leading to a reduction in the drainage of one or both kidneys and the possible migration of the clot to other parts of the body. First described by German pathologist Friedrich Daniel von Recklinghausen in 1861, RVT most commonly affects two subpopulations: newly born infants with blood clotting abnormalities or dehydration and adults with nephrotic syndrome.

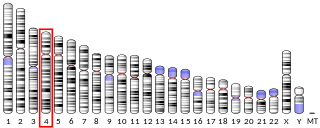

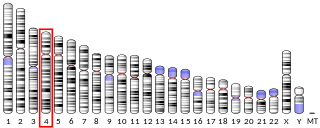

P-selectin is a type-1 transmembrane protein that in humans is encoded by the SELP gene.

Activated protein C resistance (APCR) is a hypercoagulability characterized by a lack of a response to activated protein C (APC), which normally helps prevent blood from clotting excessively. This results in an increased risk of venous thrombosis, which resulting in medical conditions such as deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. The most common cause of hereditary APC resistance is factor V Leiden mutation.

Vascular disease is a class of diseases of the vessels of the circulatory system in the body, including blood vessels – the arteries and veins, and the lymphatic vessels. Vascular disease is a subgroup of cardiovascular disease. Disorders in this vast network of blood and lymph vessels can cause a range of health problems that can sometimes become severe, and fatal. Coronary heart disease for example, is the leading cause of death for men and women in the United States.

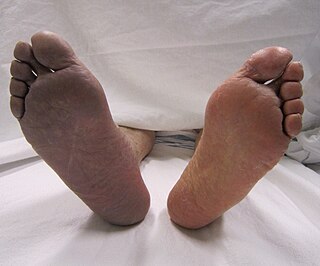

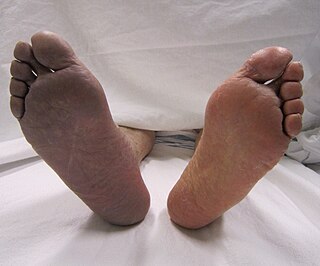

Post-thrombotic syndrome (PTS), also called postphlebitic syndrome and venous stress disorder is a medical condition that may occur as a long-term complication of deep vein thrombosis (DVT).

Hypercoagulability in pregnancy is the propensity of pregnant women to develop thrombosis. Pregnancy itself is a factor of hypercoagulability, as a physiologically adaptive mechanism to prevent post partum bleeding. However, when combined with an additional underlying hypercoagulable states, the risk of thrombosis or embolism may become substantial.

Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis (CVST), cerebral venous and sinus thrombosis or cerebral venous thrombosis (CVT), is the presence of a blood clot in the dural venous sinuses, the cerebral veins, or both. Symptoms may include severe headache, visual symptoms, any of the symptoms of stroke such as weakness of the face and limbs on one side of the body, and seizures, which occur in around 40% of patients.

Heparanase, also known as HPSE, is an enzyme that acts both at the cell-surface and within the extracellular matrix to degrade polymeric heparan sulfate molecules into shorter chain length oligosaccharides.

Superficial thrombophlebitis is a thrombosis and inflammation of superficial veins which presents as a painful induration (thickening) with erythema, often in a linear or branching configuration; forming a cord-like appearance.

Septic pelvic thrombophlebitis (SPT), also known as suppurative pelvic thrombophlebitis, is a rare postpartum complication which consists of a persistent postpartum fever that is not responsive to broad-spectrum antibiotics, in which pelvic infection leads to infection of the vein wall and intimal damage leading to thrombogenesis in the ovarian veins. The thrombus is then invaded by microorganisms. Ascending infections cause 99% of postpartum SPT.

Superficial vein thrombosis (SVT) is a blood clot formed in a superficial vein, a vein near the surface of the body. Usually there is thrombophlebitis, which is an inflammatory reaction around a thrombosed vein, presenting as a painful induration with redness. SVT itself has limited significance when compared to a deep vein thrombosis (DVT), which occurs deeper in the body at the deep venous system level. However, SVT can lead to serious complications, and is therefore no longer regarded as a benign condition. If the blood clot is too near the saphenofemoral junction there is a higher risk of pulmonary embolism, a potentially life-threatening complication.