The 1967 Detroit riot, also known as the 12th Street Riot and the Detroit Uprising, was the bloodiest of the urban riots in the United States during the "long, hot summer of 1967". Composed mainly of confrontations between black residents and the Detroit Police Department, it began in the early morning hours of Sunday July 23, 1967, in Detroit, Michigan.

The Sharpeville massacre occurred on 21 March 1960, when police opened fire on a crowd of people who had assembled outside the police station in the township of Sharpeville in the then Transvaal Province of the then Union of South Africa to protest against the pass laws. A crowd of approximately 5,000 people gathered in Sharpeville that day in response to the call made by the Pan-Africanist Congress to leave their pass-books at home and to demand that the police arrest them for contravening the pass laws. The protestors were told that they would be addressed by a government official and they waited outside the police station as more police officers arrived, including senior members of the notorious Security Branch. At 1.30pm, without issuing a warning, the police fired 1,344 rounds into the crowd. For more than fifty years the number of people killed and injured has been based on the police record, which included 249 victims in total, including 29 children, with 69 people killed and 180 injured. More recent research has shown that at least 91 people were killed at Sharpeville and at least 238 people were wounded. Many people were shot in the back as they fled from the police.

Francis Lazarro Rizzo was an American police officer and politician. He served as commissioner of the Philadelphia Police Department (PPD) from 1967 to 1971 and mayor of Philadelphia from 1972 to 1980. He was a member of the Democratic Party throughout the entirety of his career in public office. He switched to the Republican Party in 1986 and campaigned as a Republican for the final five years of his life.

The Orangeburg Massacre was a shooting of student protesters that took place on February 8, 1968, on the campus of South Carolina State College in Orangeburg, South Carolina, United States. Nine highway patrolmen and one city police officer opened fire on a crowd of African American students, killing three and injuring twenty-eight. The shootings were the culmination of a series of protests against racial segregation at a local bowling alley, marking the first instance of police killing student protestors at an American university.

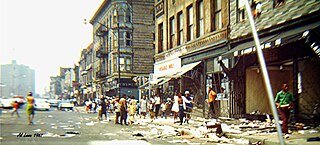

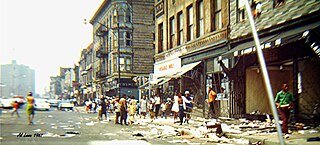

The 1967 Newark riots were an episode of violent, armed conflict in the streets of Newark, New Jersey. Taking place over a four-day period, the Newark riots resulted in at least 26 deaths and hundreds more serious injuries. Serious property damage, including shattered storefronts and fires caused by arson, left many of the city's buildings damaged or destroyed. At the height of the conflict, the National Guard was called upon to occupy the city with tanks and other military equipment, leading to iconic media depictions that were considered particularly shocking when shared in the national press. In the aftermath of the riots, Newark was quite rapidly abandoned by many of its remaining middle-class and affluent residents, as well as much of its white working-class population. This accelerated flight led to a decades-long period of disinvestment and urban blight, including soaring crime rates and gang activity.

The Philadelphia race riot, or Columbia Avenue Riot, took place in the predominantly black neighborhoods of North Philadelphia from August 28 to August 30, 1964. Tensions between black residents of the city and police had been escalating for several months over several well-publicized allegations of police brutality.

This is a timeline of African-American history, the part of history that deals with African Americans.

The School District of Philadelphia (SDP) is the school district that includes all school district-operated public schools in Philadelphia. Established in 1818, it is largest school district in Pennsylvania and the eighth-largest school district in the nation, serving over 197,000 students as of 2022.

The Soweto uprising, also known as the Soweto riots, was a series of demonstrations and protests led by black school children in South Africa during apartheid that began on the morning of 16 June 1976.

The protests of 1968 comprised a worldwide escalation of social conflicts, which were predominantly characterized by the rise of left-wing politics, anti-war sentiment, civil rights urgency, youth counterculture within the silent and baby boomer generations, and popular rebellions against military states and bureaucracies.

The Chicago Freedom Movement, also known as the Chicago open housing movement, was led by Martin Luther King Jr., James Bevel and Al Raby. It was supported by the Chicago-based Coordinating Council of Community Organizations (CCCO) and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC).

The Cambridge riots of 1963 were race riots that occurred during the summer of 1963 in Cambridge, a small city on the Eastern Shore of Maryland. The riots emerged during the Civil Rights Movement, locally led by Gloria Richardson and the local chapter of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. They were opposed by segregationists including the police.

The Harlem riot of 1964 occurred between July 16 and 22, 1964. It began after James Powell, a 15-year-old African American, was shot and killed by police Lieutenant Thomas Gilligan in front of Powell's friends and about a dozen other witnesses. Hundreds of students from Powell's school protested the killing. The shooting set off six consecutive nights of rioting that affected the New York City neighborhoods of Harlem and Bedford-Stuyvesant. By some accounts, 4,000 people participated in the riots. People attacked the New York City Police Department (NYPD), destroyed property, and looted stores. Several rioters were severely beaten by NYPD officers. The riots and unrest left one dead, 118 injured, and 465 arrested.

Woodrow Wilson Goode Sr. is a former Mayor of Philadelphia and the first African American to hold that office. He served from 1984 to 1992, a period which included the controversial MOVE police action and house bombing in 1985. Goode was also a community activist, chair of the state Public Utility Commission, and managing director for the City of Philadelphia.

All students attending the School District of Philadelphia are required to take African American History to graduate. This requirement has been in place since 2005. It was the first major city to require African American History as a requirement for high school graduation.

This is a timeline of the civil rights movement in the United States, a nonviolent mid-20th century freedom movement to gain legal equality and the enforcement of constitutional rights for people of color. The goals of the movement included securing equal protection under the law, ending legally institutionalized racial discrimination, and gaining equal access to public facilities, education reform, fair housing, and the ability to vote.

Stanley Everett Branche was an American civil rights leader from Pennsylvania who worked as executive secretary in the Chester, Pennsylvania, branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and founded the Committee for Freedom Now (CFFN).

The Chester school protests were a series of demonstrations that occurred from November 1963 through April 1964 in Chester, Pennsylvania. The demonstrations aimed to end the de facto segregation of Chester public schools that persisted after the 1954 Supreme Court case Brown v. The Board of Education of Topeka. The racial unrest and civil rights protests were led by Stanley Branche of the Committee for Freedom Now (CFFN) and George Raymond of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored Persons (NAACP).

"When the looting starts, the shooting starts" is a phrase originally used by Walter E. Headley, the police chief of Miami, Florida, in response to an outbreak of violent crime during the 1967 Christmas holiday season. He accused "young hoodlums, from 15 to 21", of taking "advantage of the civil rights campaign" that was then sweeping the United States. Having ordered his officers to combat the violence with shotguns, he told the press that "we don't mind being accused of police brutality". The quote may have been borrowed from a 1963 comment from Birmingham, Alabama police chief Bull Connor. It was featured in Headley's 1968 obituary published by the Miami Herald.

The George Floyd protests and riots in Philadelphia were a series of protests and riots occurring in the City of Philadelphia. Unrest in the city began as a response to the murder of George Floyd in police custody in Minneapolis on May 25, 2020. Numerous protests, rallies and marches took place in Philadelphia in solidarity with protestors in Minneapolis and across the United States. These demonstrations call for justice for Floyd and protest police brutality. After several days of protests and riots, Philadelphia leadership joined other major cities, including Chicago in instituting a curfew, beginning Saturday, May 30, at 8 p.m. The protests concluded on June 23, 2020.