Charleston is the most populous city in the U.S. state of South Carolina, the county seat of Charleston County, and the principal city in the Charleston metropolitan area. The city lies just south of the geographical midpoint of South Carolina's coastline on Charleston Harbor, an inlet of the Atlantic Ocean formed by the confluence of the Ashley, Cooper, and Wando rivers. Charleston had a population of 150,227 at the 2020 census. The population of the Charleston metropolitan area, comprising Berkeley, Charleston, and Dorchester counties, was estimated to be 849,417 in 2023. It ranks as the third-most populous metropolitan statistical area in the state, and the 71st-most populous in the United States.

Charleston County is located in the U.S. state of South Carolina along the Atlantic coast. As of the 2020 census, the population was 408,235, making it the third-most populous county in South Carolina. Its county seat is Charleston. It is also the largest county in the state by total area, although Horry County has a larger land area. The county was created in 1800 by an act of the South Carolina State Legislature.

North Charleston is a city in Berkeley, Charleston, and Dorchester counties in the U.S. state of South Carolina. As of the 2020 census, North Charleston had a population of 114,852, making it the third-most populous city in the state, and the 248th-most populous city in the United States. North Charleston is a principal city within the Charleston-North Charleston, SC Metropolitan Statistical Area, which had an estimated population of 849,417 in 2023.

Ralph David Abernathy Sr. was an American civil rights activist and Baptist minister. He was ordained in the Baptist tradition in 1948. As a leader of the civil rights movement, he was a close friend and mentor of Martin Luther King Jr. He collaborated with King and E. D. Nixon to create the Montgomery Improvement Association, which led to the Montgomery bus boycott and co-created and was an executive board member of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). He became president of the SCLC following the assassination of King in 1968; he led the Poor People's Campaign in Washington, D.C., as well as other marches and demonstrations for disenfranchised Americans. He also served as an advisory committee member of the Congress on Racial Equality (CORE).

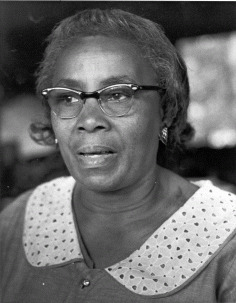

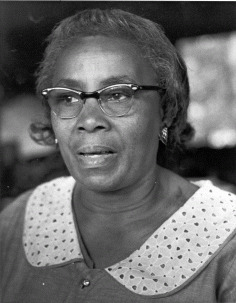

Septima Poinsette Clark was an African American educator and civil rights activist. Clark developed the literacy and citizenship workshops that played an important role in the drive for voting rights and civil rights for African Americans in the Civil Rights Movement. Septima Clark's work was commonly under-appreciated by Southern male activists. She became known as the "Queen Mother" or "Grandmother" of the Civil Rights Movement in the United States. Martin Luther King Jr. commonly referred to Clark as "The Mother of the Movement". Clark's argument for her position in the Civil Rights Movement was one that claimed "knowledge could empower marginalized groups in ways that formal legal equality couldn't."

The Poor People's Campaign, or Poor People's March on Washington, was a 1968 effort to gain economic justice for poor people in the United States. It was organized by Martin Luther King Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), and carried out under the leadership of Ralph Abernathy in the wake of King's assassination in April 1968.

MUSC Health University Medical Center is a university hospital associated with the Medical University of South Carolina, based in Charleston, South Carolina with additional sites located throughout the state.

The Memphis sanitation strike began on February 12, 1968, in response to the deaths of sanitation workers Echol Cole and Robert Walker. The deaths served as a breaking point for more than 1,300 African American men from the Memphis Department of Public Works as they demanded higher wages, time and a half overtime, dues check-off, safety measures, and pay for the rainy days when they were told to go home.

The history of Charleston, South Carolina, is one of the longest and most diverse of any community in the United States, spanning hundreds of years of physical settlement beginning in 1670. Charleston was one of leading cities in the South from the colonial era to the Civil War in the 1860s. The city grew wealthy through the export of rice and, later, sea island cotton and it was the base for many wealthy merchants and landowners. Charleston was the capital of American slavery.

The Martin Luther King, Jr. County Labor Council (MLKCLC) is the central body of labor organizations in King County, Washington. The MLKCLC is affiliated with the national AFL–CIO, the central labor organization in the United States, which represents more than 13 million working people. Over 125 organizations are affiliated with the MLKCLC, and more than 75,000 working men and women belong to Council-affiliated organizations. In addition to supporting labor organizations, it acts as a voice for the interests and needs of the working people in King County, WA.

The following is a timeline of the history of Charleston, South Carolina, USA.

The St. Petersburg sanitation strike of 1968 was a labor strike by city sanitation workers in St. Petersburg, Florida that lasted an estimated four months. The strike of 1968 was one of three labor strikes that took place within three years by city sanitation workers, who cited grievances of pay inequality and poor working conditions. A wage dispute over a newly implemented 48-hour work week triggered the sanitation strike which lasted 116 days. 211 sanitation workers participated in the work stoppage, 210 of whom were African-American. The racial makeup of the strikers increased tensions surrounding the work stoppage and impaired social race relations in the city.Strikers participated in nonviolent marches, economic boycotts, picketing, and human blockades which eventually turned violent with four nights of riots. During the four-month strike, sanitation crew chief Joe Savage led nearly 40 marches down to City Hall, and participated in nonviolent protests which resulted in mass arrests. The strike gained the attention of local and national civil rights advocates, designating this as a significant event in the city's history.

Black South Carolinians are residents of the state of South Carolina who are of African American ancestry. This article examines South Carolina's history with an emphasis on the lives, status, and contributions of African Americans. Enslaved Africans first arrived in the region in 1526, and the institution of slavery remained until the end of the Civil War in 1865. Until slavery's abolition, the free black population of South Carolina never exceeded 2%. Beginning during the Reconstruction Era, African Americans were elected to political offices in large numbers, leading to South Carolina's first majority-black government. Toward the end of the 1870s however, the Democratic Party regained power and passed laws aimed at disenfranchising African Americans, including the denial of the right to vote. Between the 1870s and 1960s, African Americans and whites lived segregated lives; people of color and whites were not allowed to attend the same schools or share public facilities. African Americans were treated as second-class citizens leading to the civil rights movement in the 1960s. In modern America, African Americans constitute 22% of the state's legislature, and in 2014, the state's first African American U.S. Senator since Reconstruction, Tim Scott, was elected. In 2015, the Confederate flag was removed from the South Carolina Statehouse after the Charleston church shooting.

I Am Somebody is a 1970 short political documentary by Madeline Anderson about black hospital workers on strike in Charleston, South Carolina. This was the first half-hour documentary film by an African-American woman in the film industry union. This film is one of the first to link black women and the fight for civil rights.

The Atlanta sanitation strike of 1977 was a labor strike involving sanitation workers in Atlanta, Georgia, United States. Precipitated by wildcat action in January, on March 28 the local chapter of the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME) agreed to strike. The main goal of the strike was a $0.50 hourly wage increase. With support from many community groups, Atlanta mayor Maynard Jackson resisted the strike, firing over 900 striking workers on April 1. By April 16, many of the striking workers had returned to their previous jobs, and by April 29 the strike was officially ended.

Prior to the civil rights movement in South Carolina, African Americans in the state had very few political rights. South Carolina briefly had a majority-black government during the Reconstruction era after the Civil War, but with the 1876 inauguration of Governor Wade Hampton III, a Democrat who supported the disenfranchisement of blacks, African Americans in South Carolina struggled to exercise their rights. Poll taxes, literacy tests, and intimidation kept African Americans from voting, and it was virtually impossible for someone to challenge the Democratic Party, which ran unopposed in most state elections for decades. By 1940, the voter registration provisions written into the 1895 constitution effectively limited African-American voters to 3,000—only 0.8 percent of those of voting age in the state.

The Charleston sanitation strike was a more than two-month movement in Charleston, South Carolina that protested the pay and working conditions of Charleston's overwhelmingly African-American sanitation workers.

Workers for the Scripto company in Atlanta, Georgia, United States, held a labor strike from November 27, 1964, to January 9, 1965. It ended when the company and union agreed to a three-year contract that included wage increases and improved employee benefits. The strike was an important event in the history of the civil rights movement, as both civil rights leaders and organized labor activists worked together to support the strike.

The 1945–1946 Charleston Cigar Factory strike was a labor strike involving workers at the Cigar Factory in Charleston, South Carolina, United States. The strike commenced on October 22, 1945, and ended on April 1 of the following year, with the strikers winning some concessions from the company.