Typhoid fever, also known as typhoid, is a disease caused by Salmonella serotype Typhi bacteria. Symptoms vary from mild to severe, and usually begin six to 30 days after exposure. Often there is a gradual onset of a high fever over several days. This is commonly accompanied by weakness, abdominal pain, constipation, headaches, and mild vomiting. Some people develop a skin rash with rose colored spots. In severe cases, people may experience confusion. Without treatment, symptoms may last weeks or months. Diarrhea may be severe, but is uncommon. Other people may carry it without being affected, but are still contagious. Typhoid fever is a type of enteric fever, along with paratyphoid fever. S. enterica Typhi is believed to infect and replicate only within humans.

An antiseptic is an antimicrobial substance or compound that is applied to living tissue to reduce the possibility of sepsis, infection or putrefaction. Antiseptics are generally distinguished from antibiotics by the latter's ability to safely destroy bacteria within the body, and from disinfectants, which destroy microorganisms found on non-living objects.

Mary Mallon, known commonly as Typhoid Mary, was an Irish-born American cook believed to have infected between 51 and 122 people with typhoid fever. The infections caused three confirmed deaths, with unconfirmed estimates of as many as 50. She was the first person in the United States identified as an asymptomatic carrier of the pathogenic bacteria Salmonella typhi. She was forcibly quarantined twice by authorities, the second time for the remainder of her life because she persisted in working as a cook and thereby exposed others to the disease. Mallon died after a total of nearly 30 years quarantined. Her popular nickname has since become a term for persons who spread disease or other misfortune, not always aware that they are doing so.

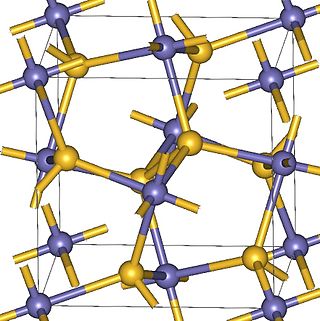

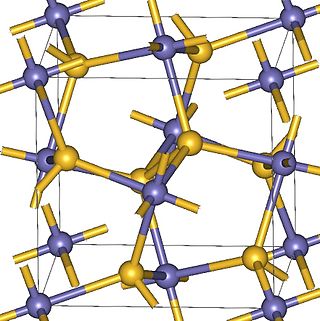

Hexamethylenetetramine, also known as methenamine, hexamine, or urotropin, is a heterocyclic organic compound with the formula (CH2)6N4. This white crystalline compound is highly soluble in water and polar organic solvents. It has a cage-like structure similar to adamantane. It is useful in the synthesis of other organic compounds, including plastics, pharmaceuticals, and rubber additives. It sublimes in vacuum at 280 °C.

Christian Albert Theodor Billroth was a German surgeon and amateur musician.

Brigadier General George Miller Sternberg was a U.S. Army physician who is considered the first American bacteriologist, having written Manual of Bacteriology (1892). After he survived typhoid and yellow fever, Sternberg documented the cause of malaria (1881), discovered the cause of lobar pneumonia (1881), and confirmed the roles of the bacilli of tuberculosis and typhoid fever (1886).

Carlos Juan Finlay was a Cuban epidemiologist recognized as a pioneer in the research of yellow fever, determining that it was transmitted through mosquitoes Aedes aegypti.

Chlorhexidine is a disinfectant and antiseptic with the molecular formula C22H30Cl2N10, which is used for skin disinfection before surgery and to sterilize surgical instruments. It is also used for cleaning wounds, preventing dental plaque, treating yeast infections of the mouth, and to keep urinary catheters from blocking. It is used as a liquid or a powder. It is known by the salt forms: chlorhexidine gluconate (chlorhexidine digluconate) and chlorhexidine acetate (chlorhexidine diacetate).

Philip Syng Physick was an American physician and professor born in Philadelphia. He was the first professor of surgery and later of anatomy at the University of Pennsylvania medical school from 1805 to 1831 during which time he was a highly influential teacher.

Povidone-iodine (PVP-I), also known as iodopovidone, is an antiseptic used for skin disinfection before and after surgery. It may be used both to disinfect the hands of healthcare providers and the skin of the person they are caring for. It may also be used for minor wounds. It may be applied to the skin as a liquid or a powder.

Asepsis is the state of being free from disease-causing micro-organisms. There are two categories of asepsis: medical and surgical. The modern day notion of asepsis is derived from the older antiseptic techniques, a shift initiated by different individuals in the 19th century who introduced practices such as the sterilizing of surgical tools and the wearing of surgical gloves during operations. The goal of asepsis is to eliminate infection, not to achieve sterility. Ideally, a surgical field is sterile, meaning it is free of all biological contaminants, not just those that can cause disease, putrefaction, or fermentation. Even in an aseptic state, a condition of sterile inflammation may develop. The term often refers to those practices used to promote or induce asepsis in an operative field of surgery or medicine to prevent infection.

BMJ is a British publisher of medical journals, and healthcare knowledge provider of clinical decision tools, online educational resources, and events. Established in 1840, the company is owned by the British Medical Association. The company was branded as BMJ Group until 2013.

Zinc peroxide (ZnO2) appears as a bright yellow powder at room temperature. It was historically used as a surgical antiseptic. More recently zinc peroxide has also been used as an oxidant in explosives and pyrotechnic mixtures. Its properties have been described as a transition between ionic and covalent peroxides. Zinc peroxide can be synthesized through the reaction of zinc chloride and hydrogen peroxide.

Aristides Agramonte y Simoni was a Cuban American physician, pathologist and bacteriologist with expertise in tropical medicine. In 1898 George Miller Sternberg appointed him as an Acting Assistant Surgeon in the U.S. Army and sent him to Cuba to study a yellow fever outbreak. He later served on the Yellow Fever Commission, a U.S. Army Commission led by Walter Reed which examined the transmission of yellow fever.

Iatrogenesis is the causation of a disease, a harmful complication, or other ill effect by any medical activity, including diagnosis, intervention, error, or negligence. First used in this sense in 1924, the term was introduced to sociology in 1976 by Ivan Illich, alleging that industrialized societies impair quality of life by overmedicalizing life. Iatrogenesis may thus include mental suffering via medical beliefs or a practitioner's statements. Some iatrogenic events are obvious, like amputation of the wrong limb, whereas others, like drug interactions, can evade recognition. In a 2013 estimate, about 20 million negative effects from treatment had occurred globally. In 2013, an estimated 142,000 persons died from adverse effects of medical treatment, up from an estimated 94,000 in 1990.

John Rutherford Ryley was an Australian surgeon who studied medicine in Glasgow, where he learned about Listerian antisepsis from Joseph Lister. He emigrated to New Zealand and introduced antiseptic surgery there in January 1868. Most of his career was then spent in Australia. He killed himself at the age of 46.

Hobart Ansteth Reimann (1897–1986) was an American virologist and physician. Reimann made contributions to medicine with his 1938 landmark article on atypical pneumonia ; and articles on periodic disease and the common cold (1948). He was active in the testing of streptomycin against typhoid, with "the first publicly reported successful experiments."

Lettice Digby was a British cytologist, botanist and malacologist. Her work provided the first demonstration that a fertile polyploid hybrid had formed between two cultivated plant species.

Giuseppe Sanarelli was an Italian bacteriologist who incorrectly identified the cause of yellow fever as a bacterium. It was however found later by Walter Reed that the bacterium Bacillus icterioides was a secondary infection. In 1897 he triggered the first major public debate on medical ethics when he injected yellow fever bacteria into five patients without consent, three of whom died. He also served as a senator of the Kingdom of Italy from 1920 to 1940.

The malaria therapy is an archaic medical procedure of treating diseases using artificial injection of malaria parasites. It is a type of pyrotherapy by which high fever is induced to stop or eliminate symptoms of certain diseases. In malaria therapy, malarial parasites (Plasmodium) are specifically used to cause fever, and an elevated body temperature reduces the symptoms of or cure the diseases. As the primary disease is treated, the malaria is then cured using antimalarial drugs. The method was developed by Austrian physician Julius Wagner-Jauregg in 1917 for the treatment of neurosyphilis for which he received the 1927 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.