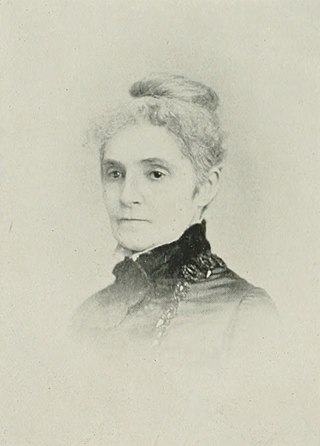

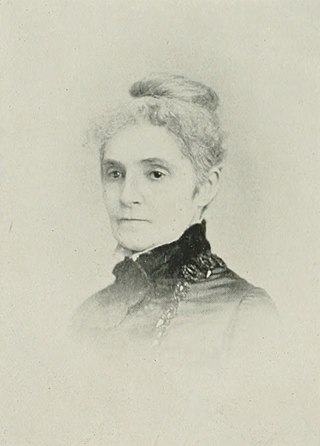

Isabella Mary Beeton, known as Mrs Beeton, was an English journalist, editor and writer. Her name is particularly associated with her first book, the 1861 work Mrs Beeton's Book of Household Management. She was born in London and, after schooling in Islington, north London, and Heidelberg, Germany, she married Samuel Orchart Beeton, an ambitious publisher and magazine editor.

The Culture of Domesticity or Cult of True Womanhood[a] is a term used by historians to describe what they consider to have been a prevailing value system among the upper and middle classes during the 19th century in the United States. This value system emphasized new ideas of femininity, the woman's role within the home and the dynamics of work and family. "True women", according to this idea, were supposed to possess four cardinal virtues: piety, purity, domesticity, and submissiveness. The idea revolved around the woman being the center of the family; she was considered "the light of the home".

Eliza Lynn Linton was the first female salaried journalist in Britain and the author of over 20 novels. Despite her path-breaking role as an independent woman, many of her essays took a strong anti-feminist slant.

Critical scholars have pointed to the status of women in the Victorian era as an illustration of the striking discrepancy of the United Kingdom's national power and wealth when compared to its social conditions. The era is named after Queen Victoria. Women did not have the right to vote or sue, and married women had limited property ownership. At the same time, women labored within the paid workforce in increasing numbers following the Industrial Revolution. Feminist ideas spread among the educated middle classes, discriminatory laws were repealed, and the women's suffrage movement gained momentum in the last years of the Victorian era.

(Jane) Emily Gerard was a Scottish 19th-century author best known for the influence her collections of Transylvanian folklore had on Bram Stoker's 1897 novel Dracula.

Ada Chard Williams was a baby farmer who was convicted of strangling to death 21-month-old Selina Ellen Jones in Barnes in London in September 1899.

Lena Kellogg Sadler was an American physician, surgeon, obstetrician, and eugenicist who was a leader in women's health issues.

Dame Mary Ann Dacomb Scharlieb, DBE was a pioneer British female physician and gynaecologist in the late 19th/early 20th centuries. She had worked in India. She was the first female student of medicine at Madras Medical College. After her graduation and work in India, she went to England to do her Postgraduation in Medicine (gynecology) and by her persistence she returned to the UK to become a qualified doctor. She returned to Madras and eventually lectured in London. She was the first woman to be elected to the honorary visiting staff of a hospital in the UK and one of the most distinguished women in medicine of her generation.

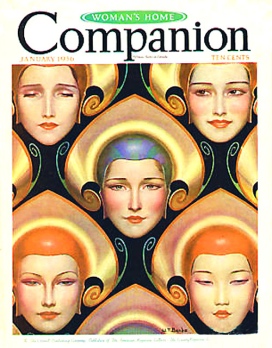

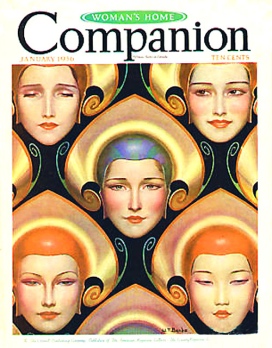

Woman's Home Companion was an American monthly magazine, published from 1873 to 1957. It was highly successful, climbing to a circulation peak of more than four million during the 1930s and 1940s. The magazine, headquartered in Springfield, Ohio, was discontinued in 1957.

The Englishwoman's Domestic Magazine (EDM) was a monthly magazine which was published between 1852 and 1879. Initially, the periodical was jointly edited by Isabella Mary Beeton and her husband Samuel Orchart Beeton, with Isabella contributing to sections on domestic management, fashion, embroidery and even translations of French novels. Some of her contributions were later collected to form her widely acclaimed Book of Household Management. The editors sought to inform as well as entertain their readers; providing the advice of an 'encouraging friend' and 'cultivation of the mind' alongside serialised fiction, short stories and poetry. More unusually, it also featured patterns for dressmaking.

Lydia Folger Fowler was a pioneering American physician, professor of medicine, and activist. She was the second American woman to earn a medical degree and one of the first American women in medicine and a prominent woman in science. She married a phrenologist and her daughter, Jessie Allen Fowler, continued their ideas.

Mary Margaret Cameron was a Scottish artist, renowned for her depictions of everyday Spanish life. She exhibited 54 works at the Royal Scottish Academy between 1886 and 1919.

C.E. Humphry (1843–1925), who often worked under the pseudonym "Madge", was a well-known journalist in Victorian-era England who wrote for and about issues relevant to women of the time. She wrote, edited and published many works throughout her career and is perhaps best known for originating what was known as the "Lady's Letter"-style column she wrote for the publication Truth, read throughout the British Empire. She was one of the first woman journalists in England.

Anna Blount was an American physician from Chicago, and Oak Park. She was awarded Doctor of Medicine June 17, 1897 by Northwestern University. She volunteered her medical services at Hull House, a settlement house in Chicago that was founded in 1889. She encouraged other women to become physicians and was the president of the National Medical Women's Association.

Helen A. Manville was an American poet and litterateur of the long nineteenth century. Under the pen name of "Nellie A. Mann", she contributed largely for leading periodicals east and west, and obtained a national reputation as a writer of acceptable verse. At the height of her fame, she decided to stop using the pen name and assume her own. She succeeded in making both names familiar, virtually winning laurels for two cognomens, when ill-health required a pause in her literary work. A collection of her poems was published in 1875, under the title of Heart Echoes, which contained a small proportion of her many verses.

Richard Ganthony (1856–1924) was an actor and playwright. He is best known as the author of the drama A Message from Mars, which premiered in 1899.

Mary Alden Hopkins was an American journalist, essayist, and activist. She served as editor for several leading magazines and did freelance work for literary groups including The Atlantic Monthly, TheAmerican Mercury, and The New York Times magazine. Hopkins published polemical pieces in both mainstream and special-interest journals on labor reform, dress reform, birth control, pacifism, vegetarianism, and suffrage. Her creative writing was shaped by her politics as she wrote poems and novels about peace, women's suffrage, and other social issues.

Marion Moss Hartog was an English Jewish poet, author, and educator. She was the editor of the first Jewish women's periodical, The Jewish Sabbath Journal.

Mary Lucy Pendered was an English novelist with a career spanning over fifty years. Despite attaining some popularity in her day, she has subsequently fallen into obscurity.

Mary Sargent Hopkins, also known as Miss "Merrie Wheeler" and The "Outdoor Woman", was an American women's health advocate and bicycle enthusiast, that used her work to promote the domestic role of a women. In addition to this, Hopkins was a journalist, publishing many articles regarding women's health and bicycling for women. She was the founder of the women's cycling magazine "The Wheelwoman", and through this magazine promoted her beliefs on womanhood and health to her readers. Hopkins believed that women riding bicycles and being outdoors more would better their mental and physical health, and she thought that the stigma around women not being able to ride bikes should change. Although a women's advocate in the cycling and health sphere, Hopkins did not believe in the progression of women's rights in all other aspects, and she connected the work that she did back to the necessity of the domestic role of a woman.