The aging of Canada has implications for the nation's society, economy, and government policies, [1] [2] and has become a topic of public discourse during the 2020s. [3]

The aging of Canada has implications for the nation's society, economy, and government policies, [1] [2] and has become a topic of public discourse during the 2020s. [3]

After peaking at nearly four children per woman in the late 1950s, Canada's fertility rate has been on the decline, [4] creating a notable shift in age distribution. [5] Historically, the nation's fertility rate plummeted in the aftermath of the Great Depression. Following the Second World War, however, there was a baby boom that lasted until the early 1960s. [4] After modern contraception had become widely available and abortion legalized, Canadians continued to have fewer children, and Canada started to dip below replacement fertility in 1972. [4] Fertility rates declined further for most years after the Great Recession of the late 2000s. [4] Canada's job market has become increasingly competitive while the cost of living continues to increase, prompting people to have fewer children and to have them later in life. [6] During the early twenty-first century, many young adults are also concerned about the high psychological cost of parenthood and ecological crisis. But the biggest shift may be cultural in nature. Personal independence and self-actualization have replaced having children as a marker of adulthood. Furthermore, like people from other wealthy nations, Canadians no longer consider having children as a necessity or a source of fulfillment, but rather an option, and those who become parents tend to have few of them and invest more in each. [7] In 2010, around half of Canadian women without children in their 40s had decided to not have them from an early age. [8] A 2023 report by Statistics Canada states that over a third of Canadians aged 18 to 49 do not want to have children. Many are also delaying having children or want to have fewer children than their predecessors. [9]

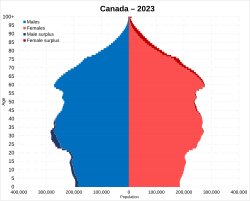

By the late 2010s, the proportion of seniors, defined as individuals aged 65 and over, has surpassed that of children under 15. [3] By 2023, about one fifth of the Canadian population was aged 65 and over. [3] This trend is driven by several factors, including increased life expectancy, declining birth rates, and the demographic impact of the baby boomer generation. [2] Baby boomers started retiring in the early 2010s and are predicted to completely leave the workforce by 2030. [10] Generation Z is simply too small as a cohort to replace them. [3] Newfoundland and Labrador, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Quebec, and Prince Edward Island have the highest concentrations of seniors of all provinces and territories. [3] It is projected that at current trend (2025), one quarter of Canadians will be older than 65 years of age by 2040. [11]

Statistics Canada reported that the nation's total fertility rate in 2024 was 1.25, putting the country in the same league as a number of other industrialized nations, such as Switzerland (1.29), Luxembourg (1.25), and Finland (1.25), but above some others, including Japan (1.15), Singapore (0.97) and South Korea (0.75). [10] As of 2023, British Columbia had the lowest fertility rate (1.02), followed by Nova Scotia (1.08), Prince Edward Island (1.10), Ontario (1.21), Quebec (1.31), the Northwest Territories (1.39), Alberta (1.41), Manitoba (1.50), and Saskatchewan (1.58). Nunavut (2.34) had the highest. [10]

Shortages of medical professionals, already a serious problem in Canada, were exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. A growing share of healthcare workers have been reaching retirement age, while their patients have become older as well, thereby increasing the demand for health services. [3] As of 2025, the average cost of providing healthcare to those aged 65 and over was $12,000, compared to just $2,700 for those below that age. [11] That large numbers of Canadians prefer aging in place for reasons of comfort, dignity, and independence stretches public resources even further. [11] However, telehealth services and assistive technologies, such as home automation, can facilitate aging in place, allowing seniors to maintain independence while receiving necessary support. [12] [13]

Populating aging will have an effect on Canadian society as a whole. Balancing work and care-giving can be a challenge for many families, as are concerns over social isolation and loneliness among seniors. [14]

While a number of seniors have accumulated or inherited sufficient wealth for a comfortable retirement, this is far from universal. Around 30 percent of Canadians using homeless shelters are aged 50 or older while others remain without shelter. [11]

Canada has the highest percentage of workers with higher education in the G7. However, Canada's productivity ranks lower than every other nation in the Group of 7 except Japan. [15] According to the Bank of Canada, young Canadians suffer from a mismatch between skills learned at school and those demanded by the work place. As a result, many new entrants to the job market find themselves either unemployed despite being highly trained, or stuck in low-wage positions. [16] As of 2025, while Canada faces high (youth) unemployment in the short run, due to global tariffs of American President Donald J. Trump, economists project that unemployment would peak by around 2030 due to population aging. [10] The mass retirement of baby boomers can lead to labor shortages, jeopardize pensions, and strain public finances. [17] In the long term, a shrinking labor force may dampen productivity and growth. Initiatives such as flexible work arrangements, age-friendly workplaces, and retraining programs have been introduced to harness the potential of older workers while addressing the economic challenges associated with an aging population. [18] Among wealthy nations, including Canada, life expectancy is projected to continue growing. An analysis by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) concludes that on average, 70 year-olds in 2022 had the same cognitive ability has a 53-year-olds in 2000, enabling older citizens to continue working and earning money. [19]

According to the Royal Bank of Canada (RBC), the provinces of British Columbia, Quebec, and Atlantic Canada would face the steepest rate of the "silver tsunami" or mass retirement. [10] Government programs like the Old Age Security (OAS) and Canada Pension Plan (CPP) aim to provide financial support to seniors, contributing to their economic well-being. [20] At current trend, the number of working Canadians per senior—the old age dependency ratio—will reach three in 2027, down from almost eight in 1976. [21]

For many years, Canada has expanded immigration partly as a response to population aging. [22] But by the mid-2020s, immigration to Canada was restricted in order to alleviate the cost-of-living crisis, including a shortage of housing. [23] The Bank of Canada estimated that in Canada's largest cities, a 1% increase in skilled immigration caused home prices to rise by 6-8%. [24] At the same time, research on developed countries suggests that a prospective immigrant must have at least a bachelor's degree or be working towards one in order to have net positive economic contribution to the host country. [24] Given the experiences of other countries around the world, pro-natalist policies are unlikely significantly increase birth rates. [25] However, thanks to good healthcare, older Canadians, like their counterparts in other industrialized nations, can retire later and accumulate more savings. Goldman Sachs estimates that at the current rate of gains in life expectancy, rich countries like Canada have an effective replacement fertility rate of 1.6 to 1.7, assuming zero immigration. [26]

A majority of Canadian seniors live at home with their spouses, in nursing homes or seniors' residences, and large numbers prefer to dwell in places where they grew up. Approximately one quarter live alone; most of these people are women, who tend to live longer than men. [3]

Population aging necessitates a reevaluation of housing and urban planning strategies, as seniors may seek age-friendly housing options that accommodate their needs, such proximity to healthcare and other essential services, [27] and social engagement. [28] In addition, walkable neighbourhoods and accessible public transit can help seniors can maintain active and engaged lifestyles. [29]