Sinology, otherwise referred to as Chinese studies, is a sub-field of area studies or East Asian studies involved in social sciences and humanities research on China. It is an academic discipline that focuses on the study of the Chinese civilization primarily through Chinese language, history, culture, literature, philosophy, art, music, cinema, and science. Its origin "may be traced to the examination which Chinese scholars made of their own civilization."

Étienne Fourmont was a French scholar and Orientalist who served as professor of Arabic at the Collège de France and published grammars on the Arabic, Hebrew, and Chinese languages.

Archibald Henry Sayce was a pioneer British Assyriologist and linguist, who held a chair as Professor of Assyriology at the University of Oxford from 1891 to 1919. He was able to write in at least twenty ancient and modern languages, and was known for his emphasis on the importance of archaeological and monumental evidence in linguistic research. He was a contributor to articles in the 9th, 10th and 11th editions of the Encyclopædia Britannica.

Arthur David Waley was an English orientalist and sinologist who achieved both popular and scholarly acclaim for his translations of Chinese and Japanese poetry. Among his honours were the CBE in 1952, the Queen's Gold Medal for Poetry in 1953, and he was invested as a Companion of Honour in 1956.

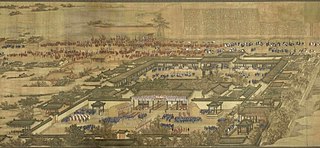

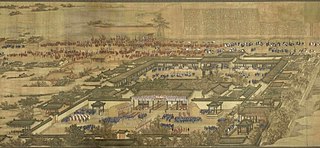

The Hanlin Academy was an academic and administrative institution of higher learning founded in the 8th century Tang China by Emperor Xuanzong in Chang'an. It has also been translated as "College of Literature" and "Academy of the Forest of Pencils."

Sir George Abraham Grierson was an Irish administrator and linguist in British India. He worked in the Indian Civil Service but an interest in philology and linguistics led him to pursue studies in the languages and folklore of India during his postings in Bengal and Bihar. He published numerous studies in the journals of learned societies and wrote several books during his administrative career but proposed a formal linguistic survey at the Oriental Congress in 1886 at Vienna. The Congress recommended the idea to the British Government and he was appointed superintendent of the newly created Linguistic Survey of India in 1898. He continued the work until 1928, surveying people across the British Indian territory, documenting spoken languages, recording voices, written forms and was responsible in documenting information on 179 languages, defined by him through a test of mutual unintelligibility, and 544 dialects which he placed in five language families. He published the findings of the Linguistic Survey in a series that consisted of 19 volumes.

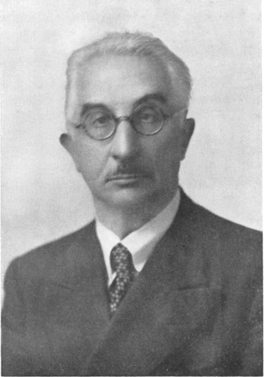

Henri Paul Gaston Maspero was a French sinologist and professor who contributed to a variety of topics relating to East Asia. Maspero is best known for his pioneering studies of Daoism. He was imprisoned by the Nazis during World War II and died in the Buchenwald concentration camp.

Émmanuel-Édouard Chavannes was a French sinologist and expert on Chinese history and religion, and is best known for his translations of major segments of Sima Qian's Records of the Grand Historian, the work's first ever translation into a Western language.

Ernest Julius Walter Simon, was a German sinologist and librarian. He was born in Berlin and lived there, being educated at the University of Berlin, until he fled the Nazis to London in 1934, where he spent all the rest of his life except for brief periods as a visiting professor in various countries, teaching Chinese at the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London from 1947 to 1960. He made great contributions to historical Chinese phonology and Sino-Tibetan linguistics. As a sinologist, he had a Chinese name, Ximen Huade.

Fellows of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland are individuals who have been elected by the Council of the Royal Asiatic Society to further "the investigation of subjects connected with and for the encouragement of science literature and the arts in relation to Asia".

Joseph Edkins was a British Protestant missionary who spent 57 years in China, 30 of them in Beijing. As a Sinologue, he specialised in Chinese religions. He was also a linguist, a translator, and a philologist. Writing prolifically, he penned many books about the Chinese language and the Chinese religions especially Buddhism. In his China's Place in Philology (1871), he tries to show that the languages of Europe and Asia have a common origin by comparing the Chinese and Indo-European vocabulary.

Peter Alexis Boodberg was a Russian-American scholar, linguist, and sinologist who taught at the University of California, Berkeley for 40 years. Boodberg was influential in 20th century developments in the studies of the development of Chinese characters, Chinese philology, and Chinese historical phonology. He has been described as "one of the most original and commanding scholars" of the 20th century.

Wonderism is a term coined by French sinologist Terrien de Lacouperie (1845-1894) to differentiate the proto-Daoism of Jixia Academy from the philosophical Daoism of Laozi, although his ideas were received with skepticism at the time of assertion and have since been discredited by modern sinology.

Édouard Constant Biot was a French engineer and Sinologist. As an engineer, he participated in the construction of the second line of French railway between Lyon and St Etienne, and as a Sinologist, published a large body of work, the result of a "knowledge rarely combined."

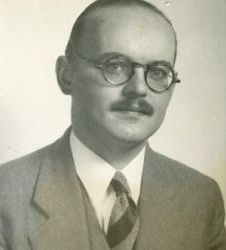

Jan Julius Lodewijk Duyvendak was a Dutch Sinologist and professor of Chinese at Leiden University. He is known for his translation of The Book of Lord Shang and his studies of the Dao De Jing. He was co-editor of the renowned sinology journal T'oung Pao with French scholar Paul Pelliot for several decades.

Paul Demiéville was a Swiss-French sinologist and Orientalist known for his studies of the Dunhuang manuscripts and Buddhism and his translations of Chinese poetry, as well as for his 30-year tenure as co-editor of T'oung Pao.

Léopold de Saussure was a Swiss-born French sinologist, pioneering scholar of ancient Chinese astronomy, and officer in the French navy. After a naval career which took him to Indochina, China, and Japan, he left the service and devoted the rest of his life to scholarship. He was most famous for his studies of ancient Chinese astronomy.

Sino-Babylonianism is a theory now rejected by most scholars that in the third millennium B.C. the Babylonian region provided the essential elements of material civilization and language to what is now China. Albert Terrien de Lacouperie (1845–1894) first proposed that a massive migration brought the basic elements of early civilization to China, but in this original form the theory was largely discredited.