Related Research Articles

Jerzy Marian Grotowski was a Polish theatre director and theorist whose innovative approaches to acting, training and theatrical production have significantly influenced theatre today. He is considered one of the most influential theatre practitioners of the 20th century as well as one of the founders of experimental theatre.

Music therapy, an allied health profession, "is the clinical and evidence-based use of music interventions to accomplish individualized goals within a therapeutic relationship by a credentialed professional who has completed an approved music therapy program." It is also a vocation, involving a deep commitment to music and the desire to use it as a medium to help others. Although music therapy has only been established as a profession relatively recently, the connection between music and therapy is not new.

Aris Christofellis is a Greek sopranist and musicologist.

Countertransference, in psychotherapy, refers to a therapist's redirection of feelings towards a patient or becoming emotionally entangled with them. This concept is central to the understanding of therapeutic dynamics in psychotherapy.

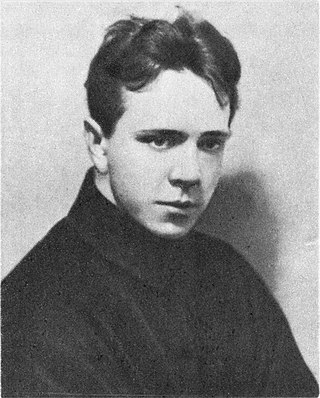

Mikhail Aleksandrovich Chekhov, known as Michael Chekhov, was a Russian-American actor, director, author, and theatre practitioner. He was a nephew of the playwright Anton Chekhov and a student of Konstantin Stanislavski. Stanislavski referred to him as his most brilliant student.

Bel canto —with several similar constructions —is a term with several meanings that relate to Italian singing.

Dartington College of Arts was a specialist arts college located at Dartington Hall in the south-west of England, offering courses at degree and postgraduate level together with an arts research programme. It existed for a period of almost 50 years, from its foundation in 1961, to when it closed at Dartington in 2010. A version of the College was then re-established in what became Falmouth University, and the Dartington title was subsequently dropped. The College was one of only a few in Britain devoted exclusively to specialist practical and theoretical studies in courses spanning right across the arts. It had an international reputation as a centre for contemporary practice. As well as the courses offered, it became a meeting point for practitioners and teachers from around the world. Dartington was known not only as a place for training practitioners, but also for its emphasis on the role of the arts in the wider community.

Margaret Frances Jane Lowenfeld was a British pioneer of child psychology and play therapy, a medical researcher in paediatric medicine, and an author of several publications and academic papers on the study of child development and play. Lowenfeld developed a number of educational techniques which bear her name and although not mainstream, have achieved international recognition.

The vocal fry register is the lowest vocal register and is produced through a loose glottal closure that permits air to bubble through slowly with a popping or rattling sound of a very low frequency. During this phonation, the arytenoid cartilages in the larynx are drawn together, which causes the vocal folds to compress rather tightly and become relatively slack and compact. This process forms a large and irregularly vibrating mass within the vocal folds that produces the characteristic low popping or rattling sound when air passes through the glottal closure. The register can extend far below the modal voice register, in some cases up to 8 octaves lower, such as in the case of Tim Storms who holds the world record for lowest frequency note ever produced by a human, a G−7, which is only 0.189 Hz, inaudible to the human ear.

Vocalists are capable of producing a variety of extended technique sounds. These alternative singing techniques have been used extensively in the 20th century, especially in art song and opera. Particularly famous examples of extended vocal technique can be found in the music of Luciano Berio, John Cage, George Crumb, Peter Maxwell Davies, Hans Werner Henze, György Ligeti, Demetrio Stratos, Meredith Monk, Giacinto Scelsi, Arnold Schoenberg, Salvatore Sciarrino, Karlheinz Stockhausen, Tim Foust, Avi Kaplan, and Trevor Wishart.

Roy Hart was a South African actor and vocalist noted for his highly flexible voice and extensive vocal range that resulted from training in the extended vocal technique developed and taught by the German singing teacher Alfred Wolfsohn at the Alfred Wolfsohn Voice Research Centre in London between 1943 and 1962.

Alfred Wolfsohn was a German singing teacher who suffered persistent auditory hallucination of screaming soldiers, whom he had witnessed dying of wounds while serving as a stretcher bearer in the trenches of World War I. Wolfsohn was diagnosed with shell shock, but did not respond to treatment. He subsequently cured himself by vocalizing extreme sounds, bringing about what he described as a combination of catharsis and exorcism.

Professor Janice L. Chapman AUA [born January 1938 ]OAM is an Australian-born soprano, voice researcher, and vocal consultant. She is the author of Singing and Teaching Singing: A Holistic Approach to Classical Voice first published by Plural Publishing Inc. at the end of 2005, and she has contributed to papers in the Journal of Voice, The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America and Australian Voice. She is also a professor of voice at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama in London.

Josephine Antoinette Estill, known as Jo Estill, was an American singer, singing voice specialist and voice researcher. Estill is best known for her research and the development of Estill Voice Training, a programme for developing vocal skills based on deconstructing the process of vocal production into control of specific structures in the vocal mechanism.

Estill Voice Training is a program for developing vocal skills based on analysing the process of vocal production into control of specific structures in the vocal mechanism. By acquiring the ability to consciously move each structure the potential for controlled change of voice quality is increased.

Robert Joseph Langs was a psychiatrist, psychotherapist, and psychoanalyst. He was the author, co-author, or editor of more than forty books on psychotherapy and human psychology. Over the course of more than fifty years, Langs developed a revised version of psychoanalytic psychotherapy, currently known as the "adaptive paradigm". This is a distinctive model of the mind, and particularly of the mind's unconscious component, significantly different from other forms of psychoanalytic and psychodynamic psychotherapy.

Paul J. Moses was a clinical professor in charge of the Speech and Voice Section, Division of Otolaryngology at the Stanford University School of Medicine, San Francisco, where he conducted research into the psychology of the human voice, seeking to show how personality traits, neuroses, and symptoms of mental disorders are evident in the vocal tone or pitch range, prosody, and timbre of a voice, independent of the speech content.

Leslie Shepard was a British author, archivist, and curator who wrote books on a range of subjects including street literature, early film, and the paranormal.

Mary O'Donnell Fulkerson (1946–2020) was an American dance teacher and choreographer. Born in the United States, she developed an approach to expressive human movement called 'Anatomical Release Technique' in the US and UK, which has influenced the practice of dance movement therapy, as seen in the clinical work of Bonnie Meekums, postmodern dance, as exemplified by the choreography of Kevin Finnan, and the application of guided meditation and guided imagery, as seen in the psychotherapeutic work of Paul Newham.

Paul Newham is a retired British psychotherapist known for developing techniques used in psychology and psychotherapy that make extensive use of the arts to facilitate and examine two forms of human communication: the interpersonal communication through which people speak aloud and listen to others, and the intrapersonal communication that enables individuals to converse silently with themselves. His methods emphasise the examination of traumatic experiences through literary and vocal mediums of expression, including creative writing, storytelling, and song. He is cited by peers as a pioneer in recognition of his original contribution to the expressive therapies.

References

- ↑ Hart, R., et al., 'An Outline of the Work of the Alfred Wolfsohn Voice Research Centre', subsequently published in 'The Roy Hart Theatre: Documentation and Interviews', Dartington Theatre Papers, ed. David Williams, Fifth Series, No. 14, pp2–7. Series ed. Peter Hulton. Dartington College of Arts, 1985.

- ↑ Newham, P. 'The Psychology of Voice and the Founding of the Roy Hart Theatre'. New Theatre Quarterly IX No. 33. February 1993 pp59-65.

- ↑ Martin, J., Voice in Modern Theatre. London. Routledge 1991.

- ↑ Roose-Evans J., Experimental Theatre: From Stanislavski to Peter Brook. 4th edn. London. Routledge 1989.

- ↑ Sharon Hall, 'An Exploration of the Therapeutic Potential of Song in Dramatherapy'. Dramatherapy Vol. 27 (1) 2005 pp13-18.

- ↑ Barbara Houseman, Voice and the Release and Exploration of Emotion and Thought from a Theatre Perspective. Dramatherapy. Vol. 16. (2–3) 1994 pp25-27.

- ↑ Anne Rust-D'Eye, 'The Sounds of the Self: Voice and Emotion in Dance Movement Therapy'. Body, Movement and Dance in Psychotherapy: An International Journal for Theory, Research and Practice Volume 8. (2) 2013 pp95-107.

- ↑ Curtin, A., 'Alternative Vocalities: Listening Awry to Peter Maxwell Davies's Eight Songs for a Mad King'. Mosaic: A Journal for the Interdisciplinary Study of Literature. Vol. 42, No. 2. June 2009. pp101-117.

- ↑ Joachim, H., Die Welt. 20 October 1969.

- ↑ Flaszen, L., 'Akropolis – Treatment of the Text.' In Grotowski, J. (ed), Towards a Poor Theatre. London. Simon & Schuster 1970.

- ↑ Smith, A. C. H., 'Orghast at Persepolis. The Complete Review'. London. Viking Adult 1973.

- ↑ Ashley, L., Essential Guide to Dance. 3rd edn. London. Hachette 2012.

- ↑ Gorguin, I., Fifth Festival of Arts. Shiraz-Persepolis. Tehran. Public Relations Bureau of the Festival of Arts. Shiraz-Persepolis 1971.

- ↑ Brook, P., The Shifting Point: Forty Years of Theatrical Exploration. London Methuen 1987.

- ↑ Helfer, R. & Loney, G. M., 'Peter Brook: Oxford to Orghast'. Contemporary Theatre Studies 27. Harwood Academic Publishers 1998.

- ↑ Shepard, L., An Empirical Therapy Based on an Extension of Vocal Range and Expression in Singing and Drama. Paper read at the Sixth International Congress of Psychotherapy, London, August 1964. Repository: Alfred Wolfsohn Voice Research Centre Archives. Curated by Leslie Shepard, Dublin, Ireland.

- ↑ Newham, P., The Singing Cure: An Introduction to Voice Movement Therapy. London: Random House 1993 and Boston: Shambhala 1994.

- ↑ Newham, P., 'Jung and Alfred Wolfsohn: Analytical Psychology and the Singing Voice. Journal of Analytical Psychology 37. 1992 pp323-336.

- ↑ Newham, P., The Prophet of Song: The Life and Work of Alfred Wolfsohn. London. Tigers Eye Press 1997.

- ↑ Salomon-Lindberg, P., interviewed by Mary Löwenthal Felstiner, Amsterdam, 23–26 March 1984; 15–20 April 1985; 6–8 July 1988; 14 July 1993.

- ↑ Salomon-Lindberg, P., interviewed by Franz Weisz, Amsterdam, 1981. Trans. Franz Weisz. Repository: Franz Weisz Film Research Archives, Amsterdam and Alfred Wolfsohn Voice Research Centre Archives. Curated by Paul Newham, London.

- ↑ Salomon-Lindberg, P., interviewed by Paul Newham, Amsterdam, August 1991. Repository: Alfred Wolfsohn Voice Research Centre Archives. Curated by Paul Newham, London.

- ↑ Wolfsohn, A., Orpheus, oder der Weg zu einer Maske. Germany 1936–1938 (Manuscript). Trans. Marita Günther. Repository: Joods Historisch Museum, Amsterdam.

- ↑ Günther, M., 'The Human Voice'. Paper read at the National Conference on Drama Therapy. Antioch University. San Francisco. November 1986. Repository: Roy Hart Theatre Archives, Malérargues, France. Curated by Marita Günther and the Roy Hart Theatre.

- ↑ Salomon-Lindberg, P., interviewed by Mary Löwenthal Felstiner, Amsterdam, 23–26 March 1984; 15–20 April 1985; 6–8 July 1988; 14 July 1993. Trans. Franz Weisz. Repository: Franz Weisz Film Research Archives, Amsterdam and Alfred Wolfsohn Voice Research Centre Archives. Curated by Paul Newham, London.

- ↑ Salomon-Lindberg, P., interviewed by Franz Weisz, Amsterdam, 1981. Trans Franz Weisz. Repository: Franz Weisz Film Research Archives, Amsterdam and Alfred Wolfsohn Voice Research Centre Archives. Curated by Paul Newham, London.

- ↑ Salomon-Lindberg, P., interviewed by Paul Newham, Amsterdam, August 1991. Repository: Alfred Wolfsohn Voice Research Centre Archives. Curated by Paul Newham, London.

- ↑ Coghlan, B., 'The Human Voice and the Aural Vision of the Soul'. Paper read at the First International Conference on Scientific Aspects of Theatre at Karpacz, Poland, September 1979. Repository: Roy Hart Theatre Archives, Malérargues, France.

- ↑ Cole, E., Commentary. Paper documenting the development of the Alfred Wolfsohn Voice Research Centre from 1943 – 1953. 1953. Repository: Alfred Wolfsohn Voice Research Centre Archives. Curated by Paul Newham, London.

- ↑ Shepard, L., interviewed by Paul Newham, Dublin, 1990. Repository: Alfred Wolfsohn Voice Research Centre Archives. Curated by Paul Newham, London.

- ↑ Günther, M., 'The Human Voice: On Alfred Wolfsohn'. Spring: A Journal of Archetype and Culture 50. 1990 pp65–75.

- ↑ Newham, P. Therapeutic Voicework: Principles and Practice for the Use of Singing as a Therapy. London, Jessica Kingsley Publishers 1998.

- ↑ Newham, P. 'Voicework as Therapy: The Artistic use of Vocal Sound to Heal Mind and Body. In S. K. Levine and E. G. Levine (eds) Foundations of Expressive Therapy: Theoretical and Clinical Perspectives. London. Jessica Kingsley Publishers 1999 pp89 -112.

- ↑ Freeden, H., 'A Jewish Theatre under the Swastika'. LBI Yearbook 1. 1956.

- ↑ Schwarz, B., 'The Music World in Migration – The Muses Flee Hitler: Cultural Transfer and Adaptation 1930–1945. Jarrell C. Jackman and Carla M. Borden (eds). Washington D.C. Smithsonian Institution 1983.

- ↑ Blue, L., 'Interview with Paul Newham'. London October 1996. Cited in 'The Prophet of Song: The Life and Work of Alfred Wolfsohn. Tigers Eye Press. 1997.

- ↑ Luchsinger, R. and Dubois, C.L., 'Phonetische und stroboskopische Untersüchungen an einem Stimmphänomen', Folia Phoniatrica, 8: No. 4, pp201–210. Trans. Ian Halcrow. 1956.

- ↑ Waterhouse, J. F., 'The Utopian Voice in Birmingham: Alfred Wolfsohn's Demonstration', Birmingham Post. 17 October 1955.

- ↑ Waterhouse, J. F., 'Night-Queen Sings Sarastro', Birmingham Post (newspaper), 17 October 1955.

- ↑ Weiser, E., 'Stimme Ohne Fessel', Die Weltwoche. 30 September 1955. Trans. Ian Halcrow. Repository: Alfred Wolfsohn Voice Research Centre Archives. Curated by Paul Newham, London.

- ↑ Young, W., 'A New Kind of Voice', The Observer. 26 February 1956. Repository: Alfred Wolfsohn Voice Research Centre Archives. Curated by Paul Newham, London.

- ↑ Wolfsohn, A., Die Brücke. London 1947 (Manuscript). Trans. Marita Günther and Sheila Braggins. Repository: Joods Historisch Museum, Amsterdam.

- ↑ Günther, M., 'The Human Voice: On Alfred Wolfsohn'. Spring: A Journal of Archetype and Culture 50. 1990 pp65–75.

- ↑ Samuels, A., Jung and the PostJungians. London. Routledge. 1985.

- ↑ Stevens, A., On Jung. London. Routledge. 1990.

- ↑ Newham, P., 'The voice and the shadow'. Performance 60. Spring 1990 pp37-47.

- ↑ Jung, C.G., The Collected Works of C G Jung Vol. 11 (Bollingen Series XX). H. Read, M. Fordham, G. Adler, and Wm. McGuire (eds). Princeton, New Jersey. Princeton University Press and Routledge. 1953 pp325-6 and p544.

- ↑ Newham, P., The Prophet of Song: The Life and Work of Alfred Wolfsohn. London. Tigers Eye Press 1997.

- ↑ Shepard, L., 'The Voice of the World', (printed notes to accompany recording, with introduction by Dr Henry Cowell), 'Vox Humana: Alfred Wolfsohn's Experiments in Extension of Human Vocal Range'. New York. Folkways Records and Service Corp., Album No. FPX 123. 1956.

- ↑ Hart, R., 'How Voice Gave me a Conscience'. Paper read at the Seventh International Congress for Psychotherapy, Wiesbaden, 1967. Repository: Roy Hart Theatre Archives, Malérargues, France. Curated by Marita Günther and the Roy Hart Theatre.

- ↑ Hart, R., et al, performing 'Spoon River'. Phonograph recordings, 1957–1960. Repository: Alfred Wolfsohn Voice Research Centre Archives. Curated by Leslie Shepard, Dublin, Ireland.

- ↑ Hart, R., performing 'Carnivorous Crark' under the direction of and conducted by Alfred Wolfsohn. Phonograph recordings, 1957–1960. Repository: Alfred Wolfsohn Voice Research Centre Archives. Curated by Leslie Shepard, Dublin, Ireland.

- ↑ Hart, R., performing 'Rhapsody on a Windy Night' by T. S. Eliot under the direction of and conducted by Alfred Wolfsohn. Phonograph recordings, 1957–1960. Repository: Alfred Wolfsohn Voice Research Centre Archives. Curated by Leslie Shepard, Dublin, Ireland.

- ↑ Hart, R., performing 'The Hollow Men' by T. S. Eliot under the direction of and conducted by Alfred Wolfsohn. Phonograph recordings, 1957–1960. Repository: Alfred Wolfsohn Voice Research Centre Archives. Curated by Leslie Shepard, Dublin, Ireland.

- ↑ Hart, R., performing 'The Rocks' by T. S. Eliot under the direction of and conducted by Alfred Wolfsohn. Phonograph recordings, 1957–1960. Repository: Alfred Wolfsohn Voice Research Centre Archives. Curated by Leslie Shepard, Dublin, Ireland.

- ↑ Author unknown (initials L.S.), 'The Hoffnung Musical Festival', The Gramophone. December 1956. Repository: Alfred Wolfsohn Voice Research Centre Archives. Curated by Paul Newham, London.

- ↑ Jacobs, A., 'Mr. Hoffnung Starts a New Musical Fashion'. Evening Standard. 14 November 1956.

- ↑ Warrack, J., 'Joke Fantasy of Hoffnung Concert: Hosepipe Concerto', Daily Telegraph. 14 November 1956. Repository: Alfred Wolfsohn Voice Research Centre Archives. Curated by Paul Newham, London.

- ↑ Vox Humana: Alfred Wolfsohn's Experiments in Extension of Human Vocal Range. New York: Folkways Records and Service Corp., Album No. FPX 123, 1956.

- ↑ Günther, M., interviewed by David Williams, Malérargues, France, February 1985. Repository: Dartington College of Arts Theatre Papers Archives, Devon.

- ↑ Hart, R., et al, 'An Outline of the Work of the Alfred Wolfsohn Voice Research Centre', subsequently published in 'The Roy Hart Theatre: Documentation and Interviews', Dartington Theatre Papers, ed. David Williams, Fifth Series, No. 14, pp2–7. Series ed. Peter Hulton. Dartington College of Arts, 1985.

- ↑ The Mystery Behind the Voice: A Biography of Alfred Wolfsohn. London: Matador. 2012)

- ↑ Newham, P., The Prophet of Song: The Life and Work of Alfred Wolfsohn. London. Tigers Eye Press 1997.

- ↑ Newham, P., The Prophet of Song: The Life and Work of Alfred Wolfsohn. London. Tigers Eye Press 1997.

- ↑ Newham, P., The Prophet of Song: The Life and Work of Alfred Wolfsohn. London. Tigers Eye Press 1997.

- ↑ Hart, R., et al., 'An Outline of the Work of the Alfred Wolfsohn Voice Research Centre', subsequently published in 'The Roy Hart Theatre: Documentation and Interviews', Dartington Theatre Papers, ed. David Williams, Fifth Series, No. 14, pp2–7. Series ed. Peter Hulton. Dartington College of Arts, 1985.

- ↑ Newham, P., The Singing Cure: An Introduction to Voice Movement Therapy. London: Random House, 1993 and Boston: Shambhala, 1994.

- ↑ Pardo, E. 'Pan Theatre Information'. Web Publication: Pan Theatre Online Archived 2015-05-27 at the Wayback Machine .

- ↑ Newham, P. Therapeutic Voicework: Principles and Practice for the Use of Singing as a Therapy. London, Jessica Kingsley Publishers 1998.

- ↑ International Association for Voice Movement Therapy Online Information.

- ↑ Shaun McNiff, Sarah Povey, Jill Hayes, The Creative Arts in Dementia Care: Practical Person-Centred Approaches and Ideas. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers. 2010.

- ↑ Diane Austin, The Theory and Practice of Vocal Psychotherapy: Songs of the Self. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers. 2009.

- ↑ Noah Pikes, Dark Voices: The Genesis of Roy Hart Theatre. Spring Journal Inc. Revised edition June 1, 2004.

- ↑ Newham, P. 'Voicework as Therapy: The Artistic use of Vocal Sound to Heal Mind and Body. In S. K. Levine and E. G. Levine (eds) Foundations of Expressive Therapy: Theoretical and Clinical Perspectives. London. Jessica Kingsley Publishers 1999 pp89 -112.

- ↑ Nicole Elaine Anaka, 'Women on the verge, sounds from beyond : extended vocal technique and visions of womanhood in the vocal theatre of Meredith Monk, Diamanda Galás, and Pauline Oliveros.' University of Victoria. Doctoral Thesis 2009.