The German revolutions of 1848–1849, the opening phase of which was also called the March Revolution, were initially part of the Revolutions of 1848 that broke out in many European countries. They were a series of loosely coordinated protests and rebellions in the states of the German Confederation, including the Austrian Empire. The revolutions, which stressed pan-Germanism, liberalism and parliamentarianism, demonstrated popular discontent with the traditional, largely autocratic political structure of the thirty-nine independent states of the Confederation that inherited the German territory of the former Holy Roman Empire after its dismantlement as a result of the Napoleonic Wars. This process began in the mid-1840s.

Gustav Struve, known as Gustav von Struve until he gave up his title, was a German surgeon, politician, lawyer and publicist, and a revolutionary during the German revolutions of 1848–1849 in Baden, Germany. He also spent over a decade in the United States and was active there as a reformer.

Friedrich Franz Karl Hecker was a German lawyer, politician and revolutionary. He was one of the most popular speakers and agitators of the 1848 Revolution. After moving to the United States, he served as a brigade commander in the Union Army during the American Civil War.

Johann Christoph Gustav von Struve was a German diplomat. He was born on 26 September 1763 in Regensburg to the diplomat Anton Sebastian von Struve, the Russian ambassador to the Reichstag in Regensburg. His mother was Johanne Dorothea Werner of Sondershausen in the Thuringian states.

Johann Ludwig Karl Heinrich von Struve was the youngest son of the large brood of children of Johann Christoph Gustav von Struve and Sibilla Christiane Friederike von Hochstetter; part of the Struve family and brother to Gustav Struve.

Johann Hofer was a German lawyer.

Constantine, Prince of Hohenzollern-Hechingen, was the last Prince of Hohenzollern-Hechingen. Constantine was the only child of Frederick, Prince of Hohenzollern-Hechingen and his wife, Princess Pauline of Courland, the daughter of the last Duke of Courland, Peter von Biron.

Karl, Prince of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen was the reigning Prince of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen from 1831 to 1848.

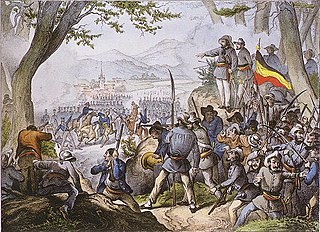

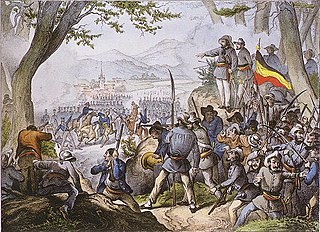

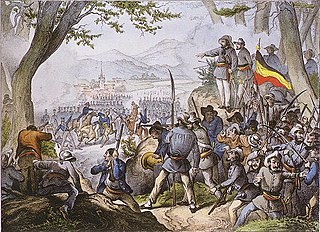

The Hecker uprising was an attempt in April 1848 by Baden revolutionary leaders Friedrich Hecker, Gustav von Struve, and several other radical democrats to overthrow the monarchy and establish a republic in the Grand Duchy of Baden. The uprising was the first major clash in the Baden Revolution and among the first in the March Revolution in Germany, part of the broader Revolutions of 1848 across Europe. The main action of the uprising consisted of an armed civilian militia under the leadership of Friedrich Hecker moving from Konstanz on the Swiss border in the direction of Karlsruhe, the ducal capital, with the intention of joining with another armed group under the leadership of revolutionary poet Georg Herwegh there to topple the government. The two groups were halted independently by the troops of the German Confederation before they could combine forces.

The Baden Revolution of 1848/1849 was a regional uprising in the Grand Duchy of Baden which was part of the revolutionary unrest that gripped almost all of Central Europe at that time.

Eugen Oswald, was a German journalist, translator, teacher and philologist who participated in the German revolutions of 1848–49.

The Palatine uprising was a rebellion that took place in May and June 1849 in the Rhenish Palatinate, then an exclave territory of the Kingdom of Bavaria. Related to uprisings across the Rhine river in Baden, it was part of the widespread Imperial Constitution Campaign (Reichsverfassungskampagne). Revolutionaries worked to defend the constitution as well as to secede from the Kingdom of Bavaria.

The Struve Putsch, also known as the Second Baden Uprising or Second Baden Rebellion, was a regional, South Baden element of the German Revolution of 1848/1849. It began with the proclamation of the German Republic on 21 September 1848 by Gustav Struve in Lörrach and ended with his arrest on 25 September 1848 in Wehr.

The Battle on the Scheideck, also known as the Battle of Kandern took place on 20 April 1848 during the Baden Revolution on the Scheideck Pass southeast of Kandern in south Baden in what is now southwest Germany. Friedrich Hecker's Baden band of revolutionaries encountered troops of the German Confederation under the command of General Friedrich von Gagern. After several negotiations and some skirmishing a short battle ensued on the Scheideck, in which von Gagern fell and the rebels were scattered. The German Federal Army took up the pursuit and dispersed a second revolutionary force that same day under the leadership of Joseph Weißhaar. The Battle on the Scheideck was the end of the road for the two rebel forces. After the battle, there were disputes over the circumstances of von Gagern's death.

Charles Egon II, Prince of Fürstenberg was a German politician and nobleman. From 1804 to 1806 he was the last sovereign prince of Furstenburg before its mediatisation, whilst still in his minority. He also served as the first-ever vice-president of the Upper Chamber of the Badische Ständeversammlung.

Elise Blenker was the wife of Louis Blenker, a German revolutionary officer of the years 1848/1849. Elise was also actively involved in various actions of the German revolutions of 1848–49 in the Palatinate and in Baden.

Events from the year 1848 in Germany.

The Baden Army was the military organisation of the German state of Baden until 1871. The origins of the army were a combination of units that the Badenese margraviates of Baden-Durlach and Baden-Baden had set up in the Baroque era, and the standing army of the Swabian Circle, to which both territories had to contribute troops. The reunification of the two small states to form the Margraviate of Baden in 1771 and its subsequent enlargement and elevation by Napoleon to become the Grand Duchy of Baden in 1806 created both the opportunity and obligation to maintain a larger army, which Napoleon used in his campaigns against Austria, Prussia and Spain and, above all, Russia. After the end of Napoleon's rule, the Grand Duchy of Baden contributed a division to the German Federal Army. In 1848, Badenese troops helped to suppress the Hecker uprising, but a year later a large number sided with the Baden revolutionaries. After the violent suppression of the revolution by Prussian and Württemberg troops, the army was re-established and fought in the Austro-Prussian War of 1866 on the side of Austria and the southern German states, as well as in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870 on the side of the Germans. When Baden joined the German Empire in 1870/71, the Grand Duchy gave up its military sovereignty and the Badenese troops became part of the XIV Army Corps of the Imperial German Army.

The German Democratic Legion was a volunteer unit formed by exiled German craftsmen and other emigrants in Paris under the leadership of the socialist poet Georg Herwegh, which set out for the Grand Duchy of Baden at the beginning of the German Revolution of 1848 to support the radical democratic Hecker uprising against the Baden government. A week after the military defeat of the uprising, the German Democratic Legion was also defeated and wiped out by Württemberg troops on April 27, 1848 in the battle of Dossenbach.

Adolf Marschall von Bieberstein was a Baden politician and diplomat.