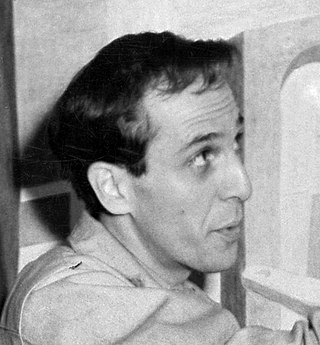

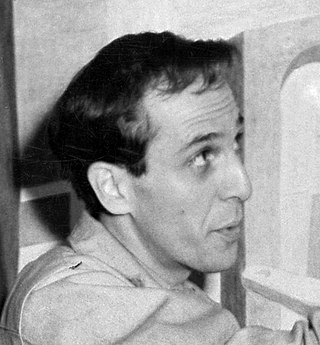

Philip Guston was a Canadian American painter, printmaker, muralist and draftsman. "Guston worked in a number of artistic modes, from Renaissance-inspired figuration to formally accomplished abstraction," and is now regarded as one of the "most important, powerful, and influential American painters of the last 100 years." He frequently depicted racism, antisemitism, fascism and American identity, as well as, especially in his later most cartoonish and mocking work, the banality of evil. In 2013, Guston's painting To Fellini set an auction record at Christie's when it sold for $25.8 million.

Inka Essenhigh is an American painter based in New York City. Throughout her career, Essenhigh has had solo exhibitions at galleries such as Deitch Projects, Mary Boone Gallery, 303 Gallery, Stefan Stux Gallery, and Jacob Lewis Gallery in New York, Kotaro Nukaga, Tomio Koyama Gallery in Tokyo, and Il Capricorno in Venice.

Cecily Brown is a British painter. Her style displays the influence of a variety of contemporary painters, from Willem de Kooning, Francis Bacon and Joan Mitchell, to Old Masters like Rubens, Poussin and Goya. Brown lives and works in New York.

Ronald "Ron" Davis is an American painter whose work is associated with geometric abstraction, abstract illusionism, lyrical abstraction, hard-edge painting, shaped canvas painting, color field painting, and 3D computer graphics. He is a veteran of nearly seventy solo exhibitions and hundreds of group exhibitions.

Joe Bradley is an American visual artist, known for his minimalist and color field paintings. He is also the former lead singer of the punk band Cheeseburger. Bradley has been based in New York City and Amagansett.

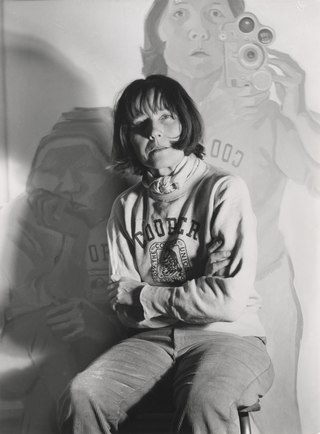

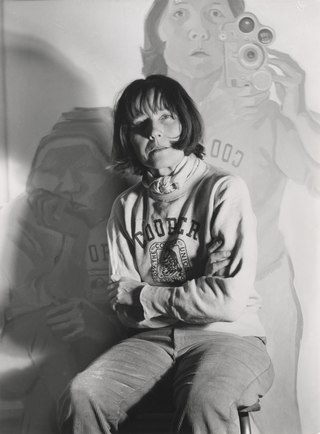

Maria Lassnig was an Austrian artist known for her painted self-portraits and her theory of "body awareness". She was the first female artist to win the Grand Austrian State Prize in 1988 and was awarded the Austrian Decoration for Science and Art in 2005. Lassnig lived and taught in Vienna from 1980 until her death.

Dannielle Tegeder is a contemporary artist who works with installation, animation and sound and is best known for her abstract paintings and drawings. She lives in Brooklyn, New York and maintains a studio at The Elizabeth Foundation in Times Square, Manhattan.

Howardena Pindell is an American artist, curator, critic, and educator. She is known as a painter and mixed media artist who uses a wide variety of techniques and materials. She began her long arts career working with the New York Museum of Modern Art, while making work at night. She co-founded the A.I.R. gallery and worked with other groups to advocate for herself and other female artists, Black women in particular. Her work explores texture, color, structures, and the process of making art; it is often political, addressing the intersecting issues of racism, feminism, violence, slavery, and exploitation. She has created abstract paintings, collages, "video drawings," and "process art" and has exhibited around the world.

Ted Stamm (1944-1984) was an American minimalist and conceptualist artist.

Ulrike Müller is a contemporary visual artist. Müller is a member of the New York-based feminist genderqueer group LTTR as well as an editor of its eponymous journal. She also represented Austria at the Cairo Biennale in 2011. She is currently a professor and co-chair of Painting at the Milton Avery Graduate School of the Arts at Bard College in Annandale-on-Hudson, New York.

Polly E. Apfelbaum is an American contemporary visual artist, who is primarily known for her colorful drawings, sculptures, and fabric floor pieces, which she refers to as "fallen paintings". She currently lives and works in New York City, New York.

Candida Alvarez is an American artist and professor, known for her paintings and drawings.

Ann Pibal is an American painter who makes geometric compositions using acrylic paint on aluminum panel. The geometric intensity is one of the key characteristics that defines her paintings.

Gina Beavers is an American artist based in the New York area. She first gained attention in the early 2010s for thickly painted, relief-like acrylic images of food, cosmetics techniques and bodybuilders appropriated from Instagram snapshots and selfies found using hashtags such as #foodporn, #sixpack and #makeuptutorial. Her later work has continued to recombine these recurrent subjects, as well as explore memes, irreverent conflations of genres or art history and kitsch, identity, fandom and celebrity-worship. In 2019, New York Times critic Martha Schwendener described her paintings as "canny statements on contemporary bodies, beauty and culture … [that] tackle the weirdness of immaterial images floating through the ether, building them up into something monumental, rather than dismissing them."

Joanna Pousette-Dart is an American abstract artist, based in New York City. She is best known for her distinctive shaped-canvas paintings, which typically consist of two or three stacked, curved-edge planes whose arrangements—from slightly precarious to nested—convey a sense of momentary balance with the potential to rock, tilt or slip. She overlays the planes with meandering, variable arabesque lines that delineate interior shapes and contours, often echoing the curves of the supports. Her work draws on diverse inspirations, including the landscapes of the American Southwest, Islamic, Mozarabic and Catalan art, Chinese landscape painting and calligraphy, and Mayan art, as well as early and mid-20th-century modernism. Critic John Yau writes that her shaped canvasses explore "the meeting place between abstraction and landscape, quietly expanding on the work of predecessors", through a combination of personal geometry and linear structure that creates "a sense of constant and latent movement."

Harriet Korman is an American abstract painter based in New York City, who first gained attention in the early 1970s. She is known for work that embraces improvisation and experimentation within a framework of self-imposed limitations that include simplicity of means, purity of color, and a strict rejection of allusion, illusion, naturalistic light and space, or other translations of reality. Writer John Yau describes Korman as "a pure abstract artist, one who doesn’t rely on a visual hook, cultural association, or anything that smacks of essentialization or the spiritual," a position he suggests few post-Warhol painters have taken. While Korman's work may suggest early twentieth-century abstraction, critics such as Roberta Smith locate its roots among a cohort of early-1970s women artists who sought to reinvent painting using strategies from Process Art, then most associated with sculpture, installation art and performance. Since the 1990s, critics and curators have championed this early work as unjustifiably neglected by a male-dominated 1970s art market and deserving of rediscovery.

Frances Barth is an American visual artist best known for paintings situated between abstraction, landscape and mapping, and in her later career, video and narrative works. She emerged during a period in which contemporary painters sought a way forward beyond 1960s minimalism and conceptualism, producing work that combined modernist formalism, geometric abstraction, referential elements and metaphor. Critic Karen Wilkin wrote, "Barth's paintings play a variety of spatial languages against each other, from aerial views that suggest mapping, to suggestions of perspectival space, to relentless flatness ... [she] questions the very pictorial conventions she deploys, creating ambiguous imagery and equally ambiguous space that seems to shift as we look."

Michelle Kuo is an American curator, writer, and art historian. Since 2018, Kuo has been a curator of painting and sculpture at the Museum of Modern Art. She was previously editor-in-chief of Artforum magazine starting in 2010.

James Little is an American painter and curator. He is known for his works of geometric abstraction which are often imbued with exuberant color. He has been based in New York City.

Robert Bordo is a New York-based, Canadian-American artist known for paintings that blend modernist formal concerns with postmodern approaches to image, subject matter and metaphor. Throughout his career, he has worked in painting series positioned between representation and abstraction that critics characterize as conceptually structured, yet sensual in execution. These series explore recurring, often overlapping themes, such as memory and experience, the passage of time, landscape and weather phenomena, mapping, and mark-making as an indicator of thought. New York Times critic Roberta Smith described Bordo's early map paintings as charting an idiosyncratic "hybrid discipline … a kind of cartographically conscious rerouting of modernism"; in a 2019 New Yorker review of his "crackup" paintings, Andrea Scott wrote, "Bordo's imagery is an apt metaphor for our current, contentious political climate, but his true subject is painting itself: how easily it can tip realism into abstraction or shift figure-ground relations until it's impossible to discern whether you’re on the inside looking out or vice versa."