Synopsis

Robinson begins by mention of the date and time of February 29, 2004 4:30 a.m., stating, "The real events of the story are very unlike those described to the general public." He knows that the conventional accounting of Aristide's removal from office is quite different than the entire history he is about to tell.

The date of December 9, 1492, is described as the most fateful of days... [1] Then, there were an estimated 8 million native Taínos living on the island of Hispaniola. "Within 20 years, there were fewer than 28,000." [2] "Thirty years on, by 1542, only 200 Taínos remained." [2] Many chapters are also entitled with a date.

November 17, 1803, is a good example. This date represents a date that Robinson describes as significant because, "It may have been the most stunning victory won for the black world in a thousand years. There has been nothing quite like it, before or since." [3] Here he is describing the defeat of slavery, in Haiti, by the Haitian revolutionary leader Toussaint Louverture. The ramification of these dates in Haitian history is monumental, per Robinson.

"As a direct result of what the Haitian revolutionaries did to free themselves, France lost two thirds of its world trade income." [4] Furthermore, the Haitian revolutionaries had a global perspective on fighting slavery. They worked with Simón Bolívar in an effort to fight slavery in South America. And they also "rolled out an unconditional welcome mat to anyone who escaped European colonialism in Africa or fled bondage from a slave plantation anywhere in the Americas, North, South, or Central." [5]

Meanwhile, in the United States Thomas Jefferson said, "If this combustion can be introduced among us under any veil whatever, we have to fear it." [6] Jefferson was fearful that the Haitian revolt might spread to slaves in America. Robinson quotes Garry Wills..."From that moment, Jefferson and the Republicans showed nothing but hostility to the new nation of Haiti." [6] Haiti had been "the most profitable slave colony in the world" [7] and "slaves were routinely worked to death, starved to death, or beaten to death.". [8] "Of the 465,000 black slaves living in Haiti when the revolt began, 150,000 would die during the 12 and a half years of fighting for their freedom." [9]

Frederick Douglass is quoted as stating that the Haitian harbor of Môle-Saint-Nicolas is of such strategic importance that, "It commands the windward passage which is the shipping lane between Haiti and Cuba." "The nation that can get it and hold it will be the master of the land and sea in its neighborhood." [10]

So for the next two hundred years, Haiti would be faced with the active hostility from the world's most powerful community of nations." [11] The hostilities came in the form of "military invasions, economic embargoes, gunboat blockades, reparations demands, trade barriers, diplomatic quarantines, subsidized armed subversions." [11] When the French departed from Haiti, they demanded reparations from Haiti of roughly $21 billion (in 2004 dollars). [12]

Robinson states that there were a number of important precedents in the Caribbean that shed light on the U.S. position towards Haiti. They included sending U.S. troops to the Dominican Republic in the early 20th century to force the Dominican Republic to give Washington the power to collect customs revenues for the U.S. at the Dominican Republic's main shipping ports. This led to the U.S. invading the Dominican Republic in 1915 and occupying the country until the end of 1924. [13]

In 1937, the Dominican Republic, under the U.S. sponsored dictatorship of Rafael Trujillo, massacred 35,000 Haitians. The American Secretary of State, Cordell Hull stated that, "Trujillo is one of the greatest men in Central America and in most of South America." [14]

In 1954 the U.S. overthrew the democratically elected government of Guatemala. This occurred, according to Robinson, because the elected president Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán raised the minimum wage to $1.08/day and he attempted moderate land reforms for the benefit of the Guatemalan people. In response to this, the U.S. accused the Guzman government of being under the influence of communism. Robinson states that the Guzmán government had no communists in their fairly elected government and that the real reason for the U.S. aggression in the area was to protect the interest of the American owned corporation, the United Fruit Company, (now called Chiquita Brands). [15]

Furthermore, Robinson says that the U.S. supported the Haitian dictators François Duvalier, and Jean-Claude Duvalier, Henri Namphy, Leslie Manigat, and Prosper Avril. [11] François Duvalier killed an estimated 50,000 Haitians. He ruled from 1957 to 1971. Jean-Claude Duvalier took control after his father died in 1971 and continued the brutal dictatorship until February 1986.

Military rulers overthrew Aristide, not just once, but twice, once in 1991 and again in 2004. Both elections of Aristide were lawful democratic elections. "There were no charges of malfeasance, either adjudicated, or formally lodged against him." [16] The elections also included the election of 7,500 other official government positions. [16]

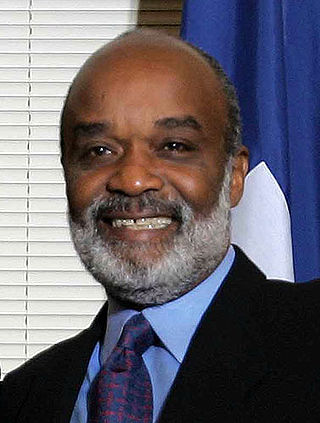

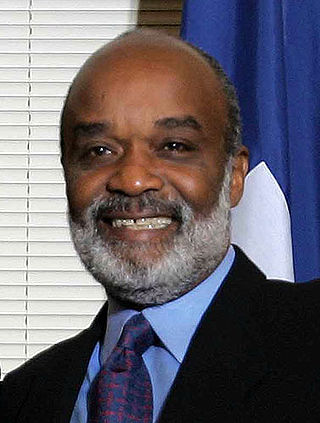

Robinson describes Aristide as "a democratic president who'd been elected twice by the largest margins on record for free elections in the Americas." [17]

In 1991, shortly after Aristide was elected, he was overthrown by General Raoul Cédras, Colonel Roger Biambi, and Police Chief Michel François. In 1994 those dictators were forced from power and democracy was restored. Cédras had been trained by the U.S. at the School of the Americas. Later, Michel François was indicted by the U.S. Justice Department for shipping large quantities of cocaine. [18]

In 1991, the former U.S. Attorney General, Ramsey Clark formed the Investigative Commission on Haiti. The Commission reported, "200 soldiers of the U.S. Special Forces arrived in the Dominican Republic with the authorization of Dominican Republic President Hipólito Mejía, as part of the military operation to train anti-democracy Haitian rebels." [19] Robinson states, "Thus they were prepared to scuttle a democracy, a constitution, an elected parliament, a functioning national government, to drive one man, Jean-Bertrand Aristide out of office, out of Haiti, indeed out of the Western Hemisphere." [20]

He continues to say, "To this wholly illegal and anti-democratic purpose, several forces cleaved as one. The armed rebels, the United States of America, France, Canada, the Dominican Republic, and a new association of Haitian opposition splinter groups forged, funded, and counseled, by the International Republican Institute, and the Convergence Démocratique, all worked towards the overthrow of the populist Aristide. Convergence Démocratique would later morph into a subversive right wing organ known as the Group of 184 " [21] Haitian anti-democratic rebel leaders included Guy Philippe, Louis-Jodel Chamblain, Ernst Ravix, and Paul Arcelin. [22]

"U.S. military officials have confirmed that 20,000 M16 rifles were given to the Dominican Republic shortly after Aristide normalized diplomatic relations with Cuba on February 6, 1996." [23]

In November 2000, Aristide was re-elected for a second term with 90% of the vote. [24] Aristide increased the number of schools, and hospitals, and he worked for the treatment and prevention of Aids. [25] He raised Haiti's minimum wage in 2003 from $1/day to $2/day." [26] He also established one standard birth certificate by eliminating the previous two-tiered race and class birth certificates." [6]

In 2002 another anti-Aristide insurrection was led by Guy Philippe, a former police precinct captain who had been trained by the CIA ." [27] Bertrand had proclaimed that France owed Haiti $21 billion (valued in current dollars) for the money France extorted from Haiti following its successful slave rebellion, [28] and when Jean-Bertrand Aristide was kidnapped and removed from office in 2004, still 1% of the population owned 50% of the country's wealth." [29]

Robinson states, "Where the poor were concerned, the United States invariably opposed the efforts of the poor's own governments, whenever and wherever those governments tried in any serious or structured way to ameliorate the poverty of their own people. If there has ever been a circumstance in which the Americans did not take the side of the rich in efforts to quash even modest reforms to help the poor, I do not know of it." [30]

In early February 2004, the anti-Aristide rebels launched their attack by "torching fire stations, and jails…and murdering rural police officers" [16] Per Robinson, on February 29, 2004, Aristide was kidnapped and driven out of office. Robinson states that the United States had always supported the wealthiest Haitian families such as the Mevs, the Bigios, the Apaids, the Boulos, the Nadals. [31]

Senator Christopher Dodd confirmed this when he said, "We had interests and ties with some of the very strong financial interests in the country and Aristide was threatening them." [32]

On January 1, 2004, Haiti celebrated its 200th birthday and 500,000 Haitians celebrated the fact that they now had a democratically elected government.

On Saturday February 7, 2004, 1,000,000 Haitian people demonstrated in support of Aristide. They were demanding that he be allowed to finish his five-year term. [33] They knew that his governance was being threatened.

The United States, however, favored the International Republican Institute (IRI) which is a U.S. non-profit organization that builds mechanisms to support "democracy" overseas. Per Robinson, despite their claims, the IRI funded right wing wealthy opponents to the Aristide government and thereby supported the opposite of democracy. Furthermore, Stanley Lucas was the senior program officer for the IRI and he had significant Duvalier affiliations.

The Bush administration through an Assistant Secretary for the Western Hemisphere, Roger Noriega, fully supported the I.R.I. [34] Jesse Helms, the Republican chairman of the US Senate Foreign Relations Committee, called Aristide "insane, dictatorial, tyrannical, corrupt and a psychopath." [35] Dominique de Villepin, the French foreign minister, blamed Aristide for "spreading violence." [36] Jamaican Prime Minister, P. J. Patterson, threatened to "impose sanctions on Aristide." [37]

The American television networks portrayed Aristide's departure in 2004 as if it were a voluntary departure. [38]

Randall Robinson spoke with Aristide on March 1, 2004, to learn then that Aristide had been transported to the Central African Republic against his will. Robinson was told by Aristide that Aristide had been forcibly removed from office in a coup. [39]

Per Robinson, the Haitian rebels who had removed Aristide from office, "had been trained by United States Special Forces." [40] They were trained "in the Dominican villages of Neiba, San Cristóbal, San Isidro, Hatillo, and Haina." [40]

Robinson states that the Armed Forces of Haiti (the Haitian Armed Forces under the Duvalier regimes), and the Front for the Advancement and Progress of Haïti (FRAPH, a paramilitary death squad that fought against democracy) massacred some 5,000 Haitians between 1991 and 1994. [41]

Louis-Jodel Chamblain, a Duvalier death squad leader, was accused of war crimes committed in 1987, 1991, 1993 and 1994 including the murder of Antoine Izméry, a pro-democracy advocate. [42]

Guy Philippe received Central Intelligence Agency training in Ecuador. He ordered paramilitary to kill Aristide supporters. Per Robinson, the opposition to democracy was "an amalgam of killers, drug runners, embezzlers, kleptocrats and sadists and included the wealthy and the elites of Haitian society." [43] Per Robinson, the United States provided the rebels with M16s, grenades, grenade launchers, M50s. [44]

Emmanuel Constant was another player in opposition to Aristide, and along with Phillipe and Chamblain, they slaughtered thousands of innocent pro-democracy civilians. [44]

After the abduction of Aristide, George W. Bush called Jacques Chirac to thank him for French cooperation in the removal of Aristide. [45]

Robinson continues, "Condoleezza Rice had directly threatened Jamaica for offering asylum to Aristide" [46] "The United States wanted Aristide not only out of Haiti but out of the Caribbean. [46]

Senator Christopher Dodd cited U.S. Department of Defense documents that indicated that the US did, in fact, supply 20,000 M16s to the Dominican Republic prior to the deposition of Aristide. [47] "American officials had armed and directed the thugs, organized an un-elected and un-electable opposition, and choked the Haitian economy into dysfunctional penury." [48]

The Central African Republic President at the time was François Bozizé. The Central African Republic is French controlled. [49] The French Defense Minister stated that the Aristides were being guarded by French soldiers in Bangui, the capital of the Central African Republic. [50]

Robinson and Maxine Waters (member of the U.S. Congress) then obtained an offer of asylum signed by P. J. Patterson, the prime minister of Jamaica. They attempted to get François Bozizé, the president of the Central African Republic, to accept it. CBS, NBC, ABC and CNN all turned down Robinson's request to join him to report on the events surrounding the removal of Aristide from office. [51] Robinson, however, did get Amy Goodman (an independent news reporter for Democracy Now!), Sharon Hay-Webster (a member of the Jamaican parliament), Peter Eisner (a deputy foreign editor at the Washington Post), Sidney Williams (a former U.S. ambassador to the Bahamas), Ira Kurzban (one of the best known lawyers in America for Immigration and Employment Law) to join him in Bangui.

Robinson states, "American decision makers only feign concern about world poverty. And they sustain the lament only so long as the pretense and its addictive but useless, solutions are profitable, directly or indirectly, to American private interests." "The force, the power plant, is money, the relentless campaign to capture it, and the God-invoked armed ruthlessness to keep it." [52]

Robinson and his entourage succeeded in getting Bozizé to release Aristide and Aristide's wife to the entourage and they took the couple to Jamaica. ." [17]

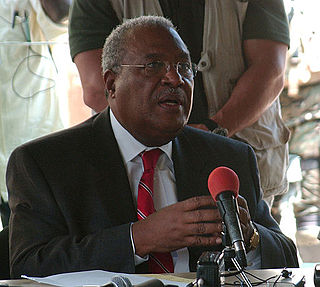

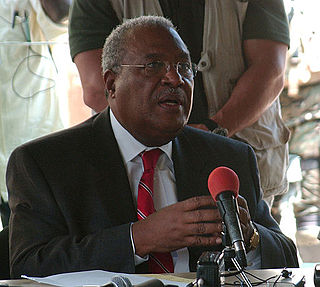

The U.S. then installed Gérard Latortue as interim president. When Latortue rescinded the Haitian demand for restitution from France, Florida House Republicans Mark Foley and Clay Shaw introduced a house resolution commending Latortue for his great service to Haiti." [53]

Robinson states that, between the day of the abduction and the election, in 2006, of René Préval, at least 4000 Haitians had been killed by the interim government." [54]

Finally, Robinson concludes by saying "as long as one member nation of the global family of nations is free to behave toward a fellow member nation with lethal impunity—to bully, to menace, to invade, to destabilize politically or economically, to reduce to tumult—no country, so threatened, can hope to enjoy the social and political contentment that ought inherently to attend democratic practices." [55]

Haiti, officially the Republic of Haiti, is a country on the island of Hispaniola in the Caribbean Sea, east of Cuba and Jamaica, and south of The Bahamas. It occupies the western three-eighths of the island, which it shares with the Dominican Republic. Haiti is the third largest country in the Caribbean, and with an estimated population of 11.4 million, is the most populous Caribbean country. The capital and largest city is Port-au-Prince.

The recorded history of Haiti began in 1492, when the European captain and explorer Christopher Columbus landed on a large island in the region of the western Atlantic Ocean that later came to be known as the Caribbean. The western portion of the island of Hispaniola, where Haiti is situated, was inhabited by the Taíno and Arawakan people, who called their island Ayiti. The island was promptly claimed for the Spanish Crown, where it was named La Isla Española, later Latinized to Hispaniola. By the early 17th century, the French had built a settlement on the west of Hispaniola and called it Saint-Domingue. Prior to the Seven Years' War (1756–1763), the economy of Saint-Domingue gradually expanded, with sugar and, later, coffee becoming important export crops. After the war which had disrupted maritime commerce, the colony underwent rapid expansion. In 1767, it exported indigo, cotton and 72 million pounds of raw sugar. By the end of the century, the colony encompassed a third of the entire Atlantic slave trade.

Jean-Bertrand Aristide is a Haitian former Salesian priest and politician who became Haiti's first democratically elected president in 1991 before being deposed in a coup d'état. As a priest, he taught liberation theology and, as president, he attempted to normalize Afro-Creole culture, including Vodou religion, in Haiti.

François Duvalier, also known as Papa Doc, was a Haitian politician and voodooist who served as the president of Haiti from 1957 until his death in 1971. He was elected president in the 1957 general election on a populist and black nationalist platform. After thwarting a military coup d'état in 1958, his regime rapidly became more autocratic and despotic. An undercover government death squad, the Tonton Macoute, indiscriminately tortured or killed Duvalier's opponents; the Tonton Macoute was thought to be so pervasive that Haitians became highly fearful of expressing any form of dissent, even in private. Duvalier further sought to solidify his rule by incorporating elements of Haitian mythology into a personality cult.

The government of Haiti is a semi-presidential republic, a multi-party system wherein the President of Haiti is head of state elected directly by popular elections. The Prime Minister acts as head of government and is appointed by the President, chosen from the majority party in the National Assembly. Executive power is exercised by the President and Prime Minister who together constitute the government. Legislative power is vested in both the government and the two chambers of the National Assembly of Haiti. The government is organized unitarily, thus the central government delegates powers to the departments without a constitutional need for consent. The current structure of Haiti's political system was set forth in the Constitution of March 29, 1987.

René Garcia Préval was a Haitian politician and agronomist who twice was President of Haiti, from early 1996 to early 2001, and again from mid-2006 to mid-2011. He was also Prime Minister from early to late 1991 under the presidency of Jean-Bertrand Aristide.

A coup d'état in Haiti on 29 February 2004, following several weeks of conflict, resulted in the removal of President Jean-Bertrand Aristide from office. On 5 February, a rebel group, called the National Revolutionary Front for the Liberation and Reconstruction of Haiti, took control of Haiti's fourth-largest city, Gonaïves. By 22 February, the rebels had captured Haiti's second-largest city, Cap-Haïtien and were besieging the capital, Port-au-Prince by the end of February. On the morning of 29 February, Aristide resigned under controversial circumstances and was flown from Haiti by U.S. military and security personnel. He went into exile, being flown directly to the Central African Republic, before eventually settling in South Africa.

Louis-Jodel Chamblain is a prominent Haitian military figure who has led both government troops and rebels.

Guy Philippe is a Haitian former police officer, politician, and convicted money launderer, who led the 2004 Haitian coup d'état against president Jean-Bertrand Aristide after being fired from the police in 2000.

The National Revolutionary Front for the Liberation and Reconstruction of Haiti was a rebel group in Haiti that controlled most of the country following the 2004 Haitian coup d'état. It was briefly known as the "Revolutionary Artibonite Resistance Front", after the country's central Artibonite region, before being renamed on February 19, 2004, to emphasize its national scope.

Gérard Latortue was a Haitian politician and diplomat who served as the prime minister of Haiti from 12 March 2004 to 9 June 2006. He was an official in the United Nations for many years, and briefly served as foreign minister of Haiti during the short-lived 1988 administration of Leslie Manigat.

Antoine Izméry was a Haitian businessman and pro-democracy activist.

Gérard Jean-Juste was a Haitian Catholic priest who served as rector of Saint Claire's Church for the Poor in Port-au-Prince. He was also a liberation theologian and a supporter of the Fanmi Lavalas political party, as well as heading the Miami, Florida-based Haitian Refugee Center from 1977 to 1990.

Randall Robinson was an American lawyer, author and activist, noted as the founder of TransAfrica. He was known particularly for his impassioned opposition to apartheid, and for his advocacy on behalf of Haitian immigrants and Haitian president Jean-Bertrand Aristide. Due to his frustration with American society, Robinson emigrated to Saint Kitts in 2001.

General elections were held in Haiti on 7 February 2006 to elect the replacements for the interim government of Gérard Latortue, which had been put in place after the 2004 Haiti rebellion. The elections were delayed four times, having originally been scheduled for October and November 2005. Voters elected a president, all 99 seats in the Chamber of Deputies of Haiti and all 30 seats in the Senate of Haiti. Voter turnout was around 60%. Run-off elections for the Chamber of Deputies of Haiti were held on 21 April, with around 28% turnout.

Jean-Claude Bajeux was a Haitian political activist and professor of Caribbean literature. For many years he was director of the Ecumenical Center for Human Rights based in Haiti's capital, Port-au-Prince, and a leader of the National Congress of Democratic Movements, a moderate socialist political party also known as KONAKOM. He was Minister of Culture during Jean-Bertrand Aristide's first term as President of Haiti.

Ertha Pascal-Trouillot is a Haitian politician who served as the provisional President of Haiti for 11 months in 1990 and 1991. She was the first woman in Haitian history to hold that office and the first female president of African descent in the Americas.

Haiti's Constitution and written laws meet most international human rights standards. In practice, many provisions are not respected. The government's human rights record is poor. Political killings, kidnapping, torture, and unlawful incarceration are common unofficial practices, especially during periods of coups or attempted coups.

The 1991 Haitian coup d'état took place on 29 September 1991, when President Jean-Bertrand Aristide, elected eight months earlier in the 1990–91 Haitian general election, was deposed by the Armed Forces of Haiti. Haitian military officers, primarily Army General Raoul Cédras, Army Chief of Staff Philippe Biamby and Chief of the National Police, Michel François led the coup. Aristide was sent into exile, his life only saved by the intervention of U.S., French, and Venezuelan diplomats. Aristide would later return to power in 1994.

Leslie Delatour (1950–2001) was a Haitian economist who served as governor of the Bank of the Republic of Haiti from 1994 to 1998, and as Haiti's Minister of Finance from 1986 to 1988.